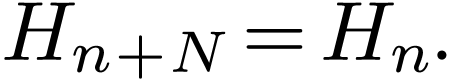

is a function of period

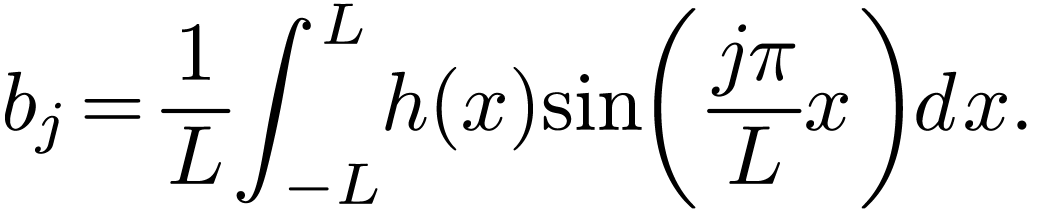

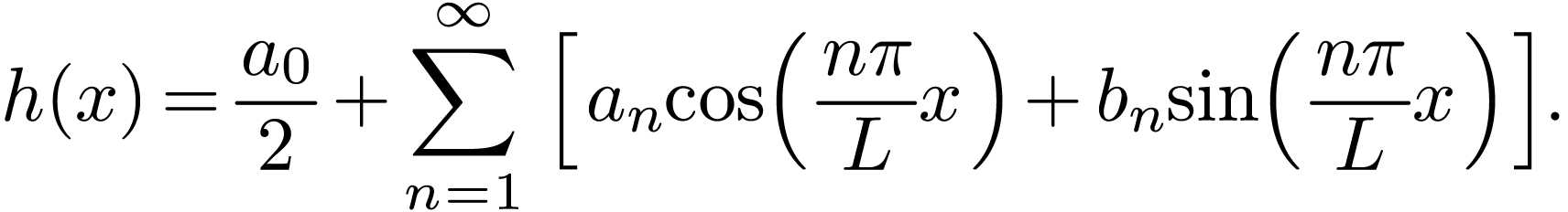

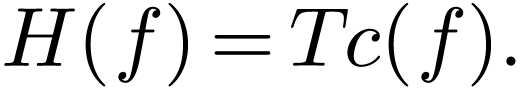

is a function of period  , then it can be proved that

, then it can be proved that  can be expressed as the following series

can be expressed as the following series

|

Abstract

This note discusses the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and its variations (e.g., the discrete sine transform).

This note discusses the Fourier expansion and Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), giving step by step derivation of DFT and its variations (e.g., the discrete sine transform). After carefully going through these elementary derivations, I feel more comfortable when using DFT in my numerical codes.

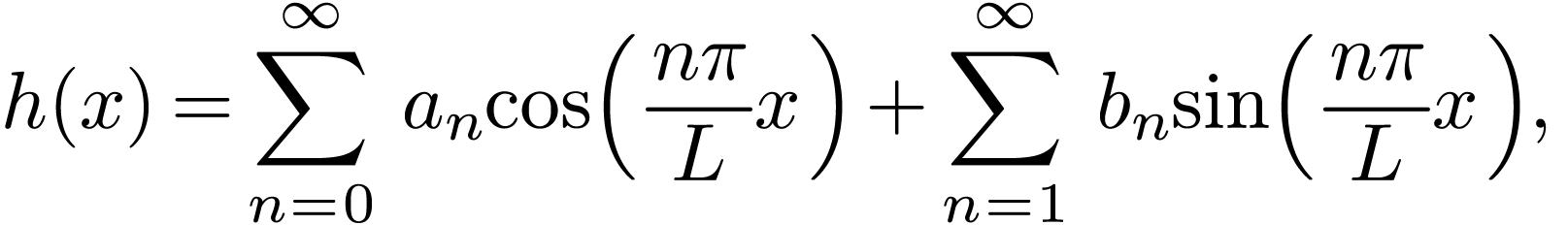

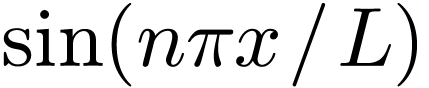

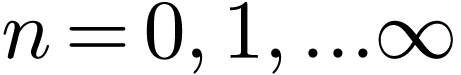

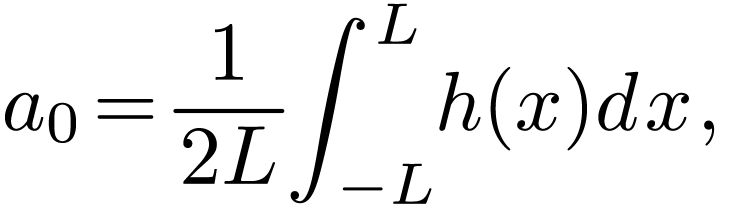

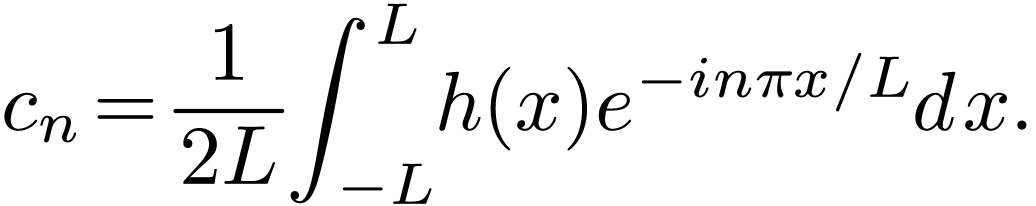

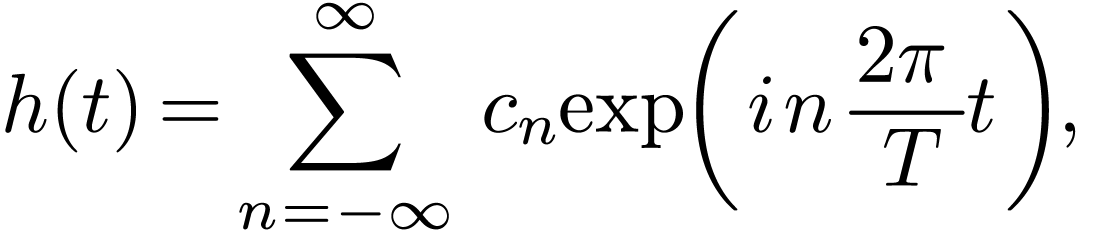

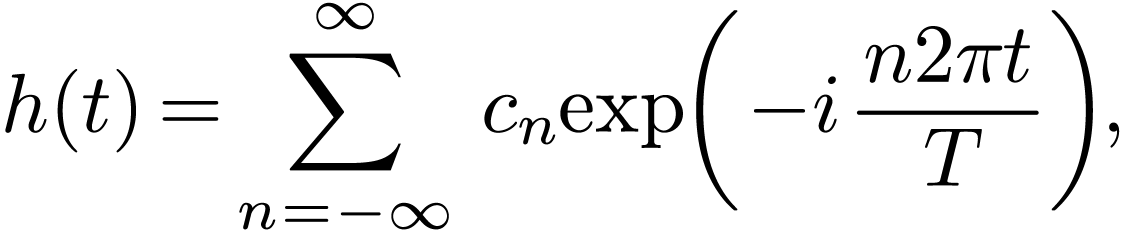

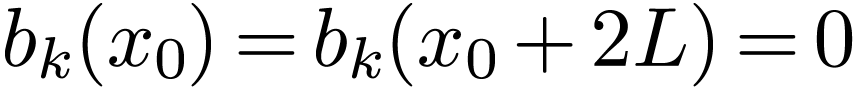

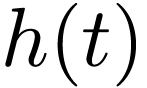

If  is a function of period

is a function of period  , then it can be proved that

, then it can be proved that  can be expressed as the following series

can be expressed as the following series

|

(1) |

which is called Fourier series. It is not trivial to prove the above

statement (what is needed in the proof is to prove that the set of

functions  and

and  with

with  is a “complete set”[1]). I

will ignore this proof and simply start with Eq. (1).

is a “complete set”[1]). I

will ignore this proof and simply start with Eq. (1).

At this point it is not clear what the coefficients  and

and  are. These can be obtained by taking product

of Eq. (1) with

are. These can be obtained by taking product

of Eq. (1) with  and

and  , respectively, and then integrating form

, respectively, and then integrating form  to

to  , which

gives

, which

gives

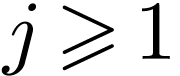

|

(2) |

and, for  ,

,

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

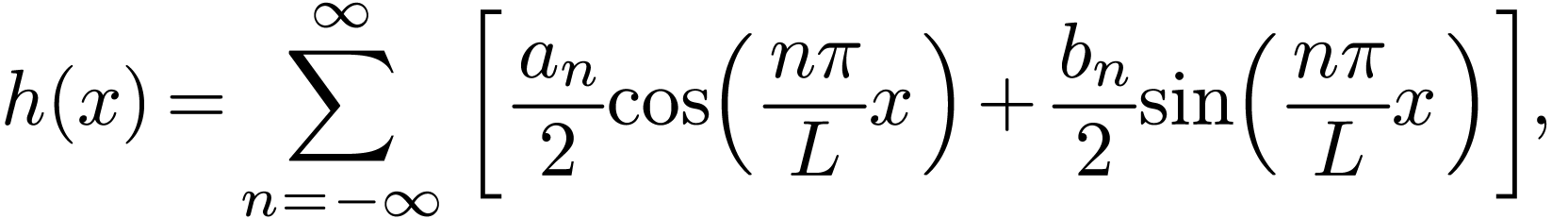

In order to enable  to be uniformly expressed by

Eq. (3), Fourier series are often redefined as

to be uniformly expressed by

Eq. (3), Fourier series are often redefined as

|

(5) |

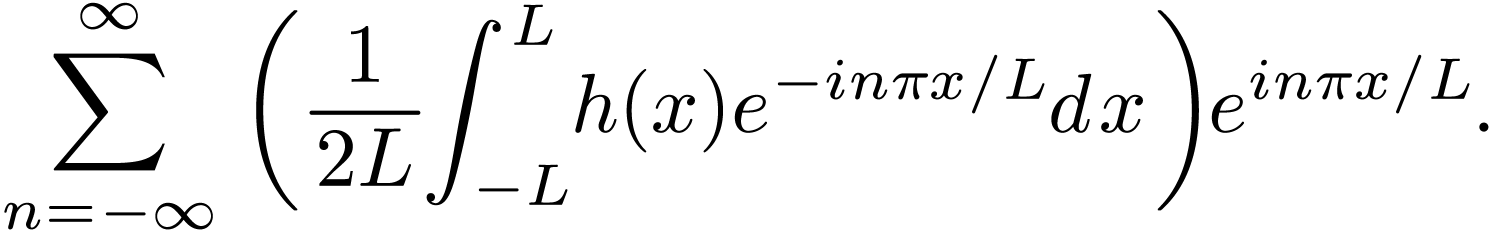

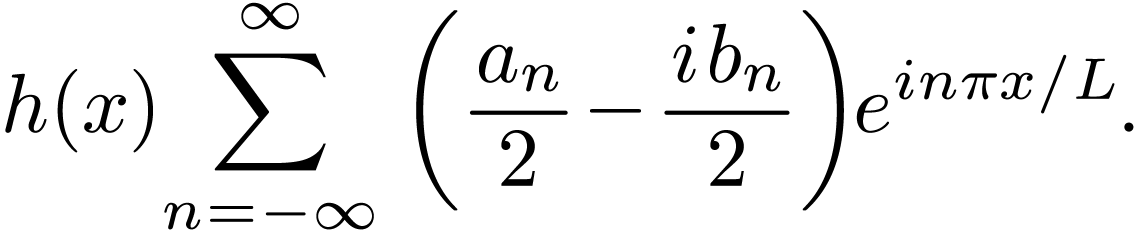

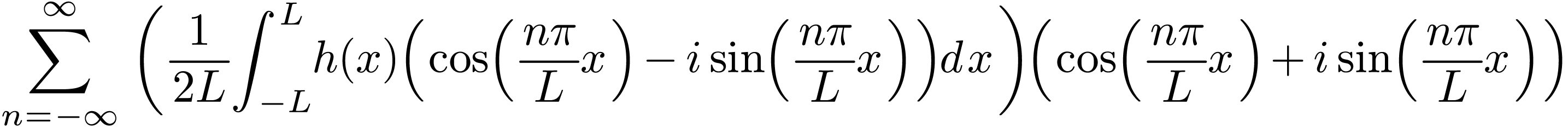

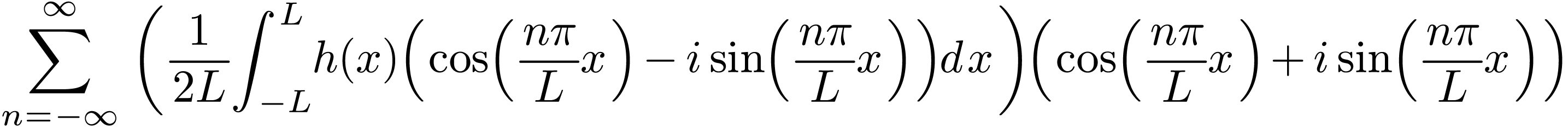

[Fourier series (5) can also be written as

|

(6) |

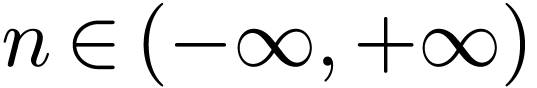

where  ranges from

ranges from  to

to

, and there is no special

treatment for the edge case of

, and there is no special

treatment for the edge case of  .

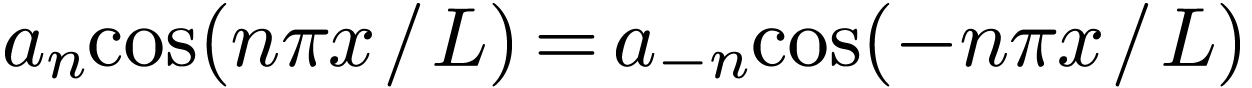

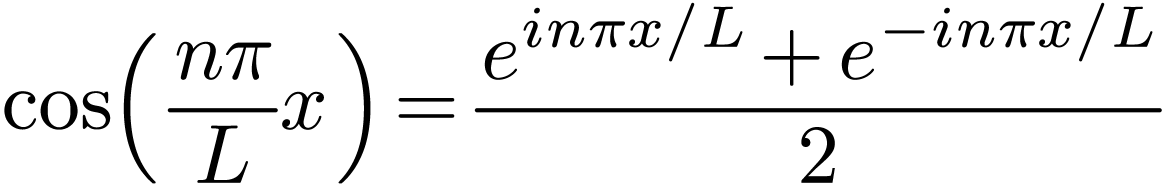

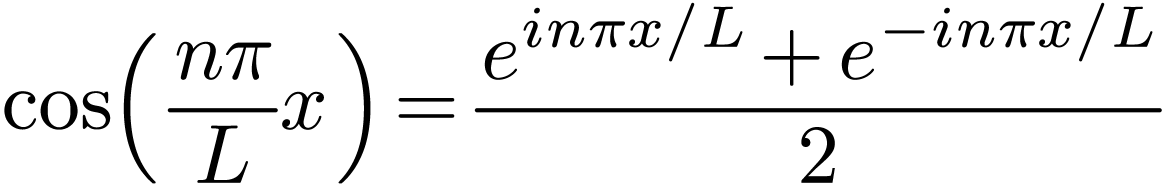

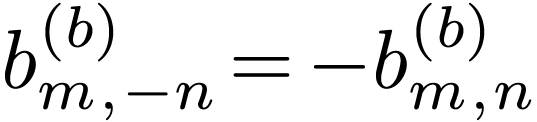

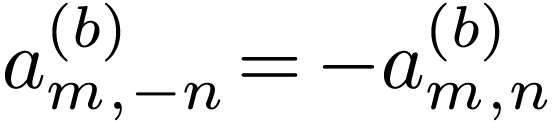

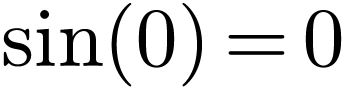

In obtaining expression (6) from (5) , use has

been made of

.

In obtaining expression (6) from (5) , use has

been made of  and

and  .]

.]

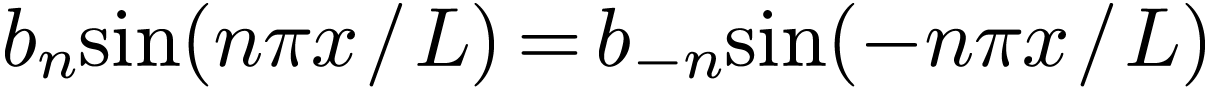

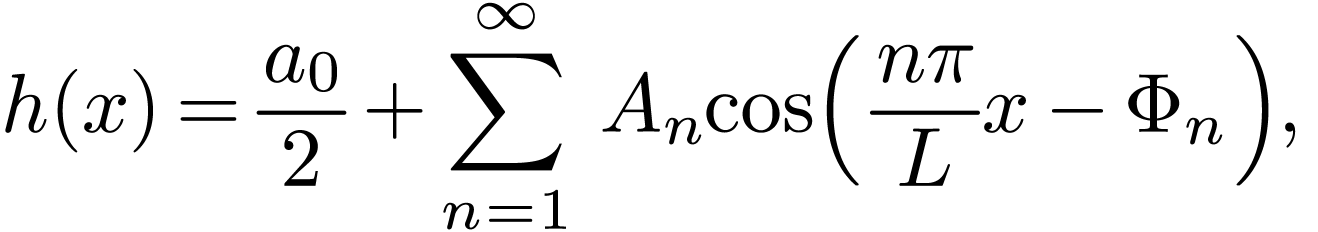

Note that sine and cosine are similar to each other: one can be

obtained from the other by shifting, i.e., they differs only in the

“phase”. For real-valued function  , using trigonometric identities, expression (5) can be expressed in terms of only cosine:

, using trigonometric identities, expression (5) can be expressed in terms of only cosine:

|

(7) |

where the amplitude  is given by

is given by

|

(8) |

and the phase  is given by

is given by

|

(9) |

where  is the 2-argument arctangent, which gives

an angle in the correct quadrant. Expresion (7) can be

stated as: a periodic signal is composed of cosine functions of

different frequencies and phases).

is the 2-argument arctangent, which gives

an angle in the correct quadrant. Expresion (7) can be

stated as: a periodic signal is composed of cosine functions of

different frequencies and phases).

(If  is a complex-valued function (the

independent variable

is a complex-valued function (the

independent variable  is still real number), then

the above Fourier expansion can be applied to its real part and

imaginary part, respectively. Combining the results, we can see that

Eqs. (3)-(5) is still valid. In this case,

is still real number), then

the above Fourier expansion can be applied to its real part and

imaginary part, respectively. Combining the results, we can see that

Eqs. (3)-(5) is still valid. In this case,

and

and  are complex numbers.

However, it seems rare to decompose complex-valued functions using

real-valued trigonometric basis functions.)

are complex numbers.

However, it seems rare to decompose complex-valued functions using

real-valued trigonometric basis functions.)

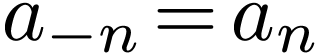

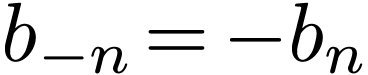

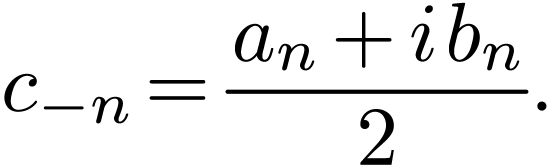

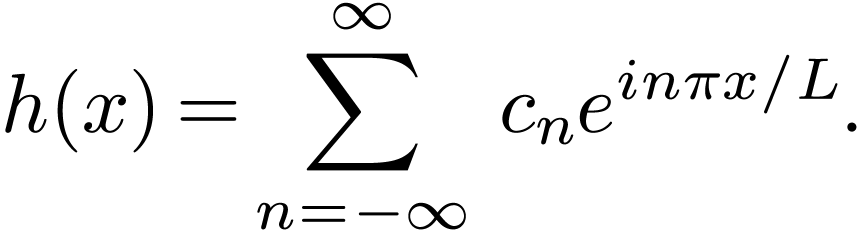

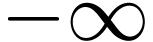

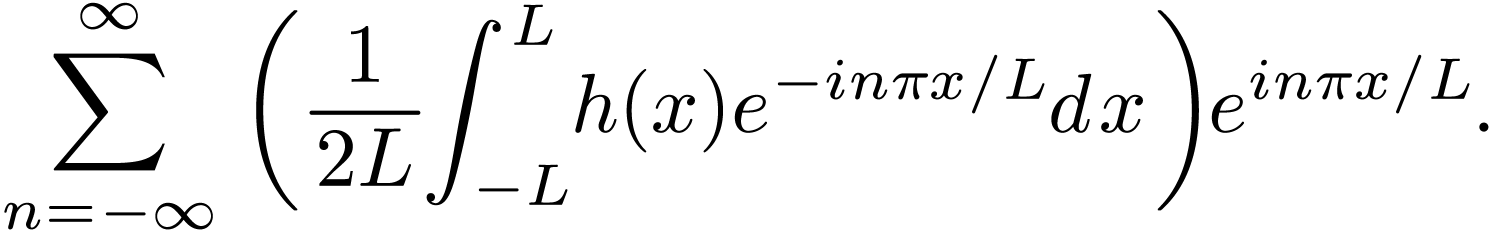

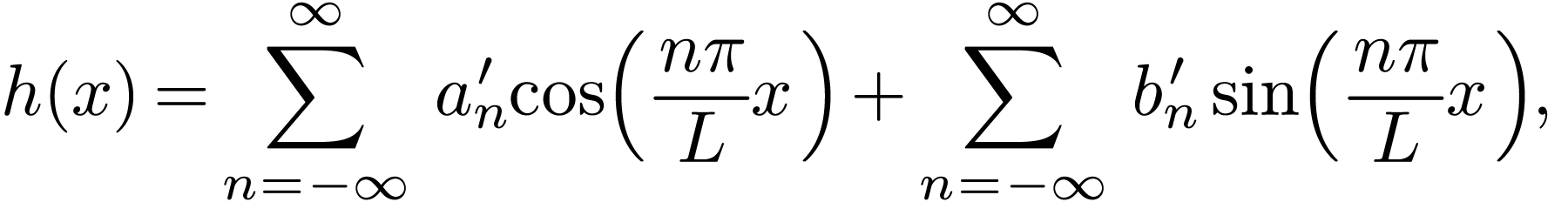

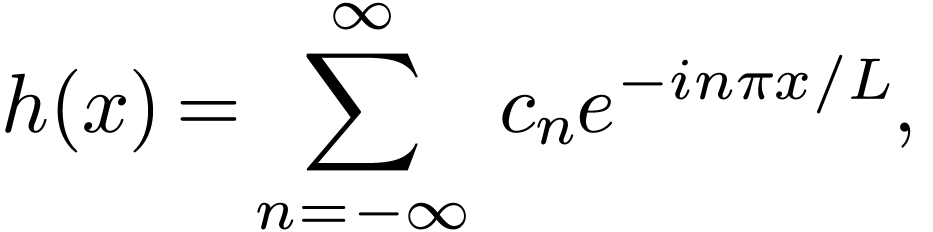

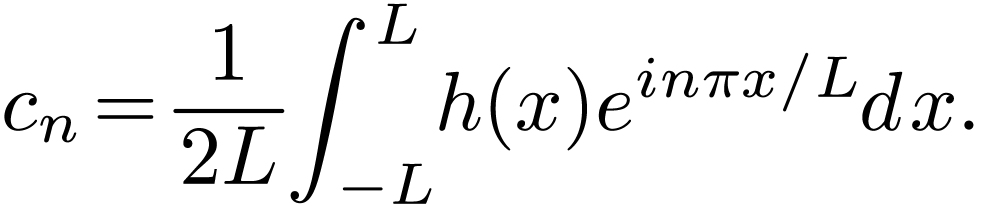

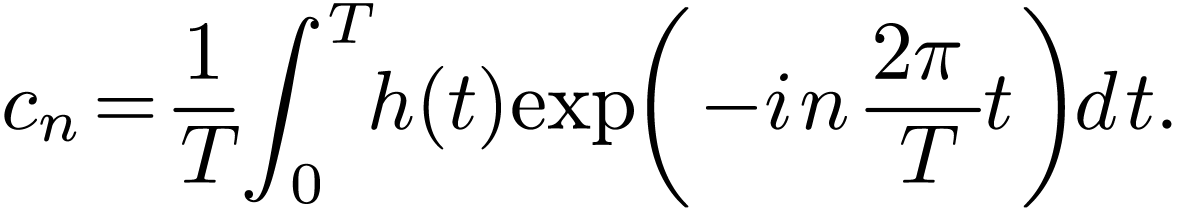

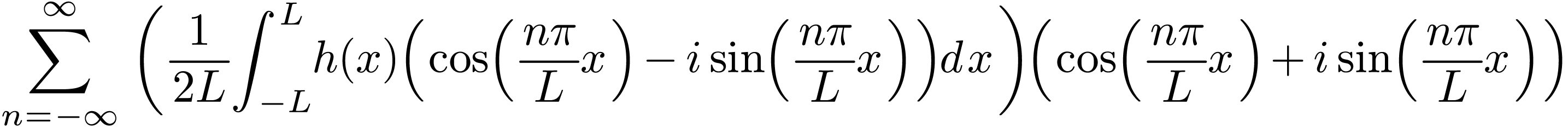

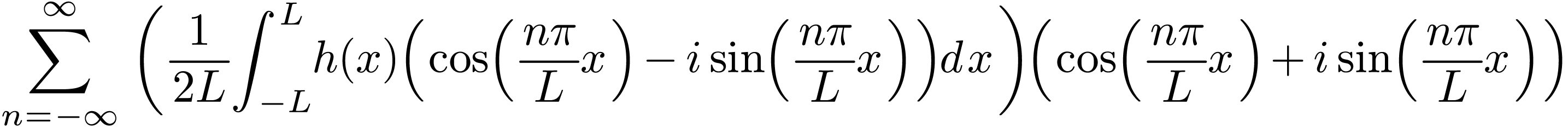

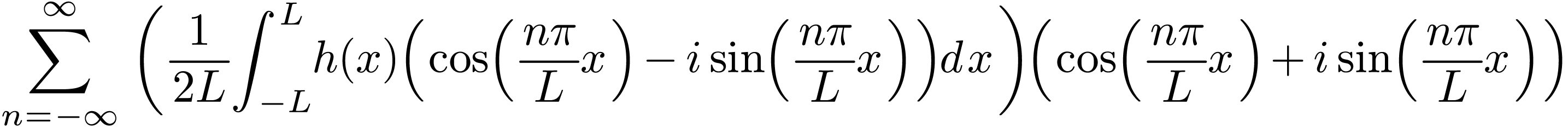

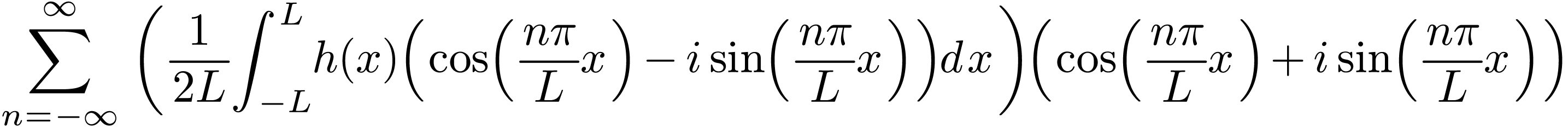

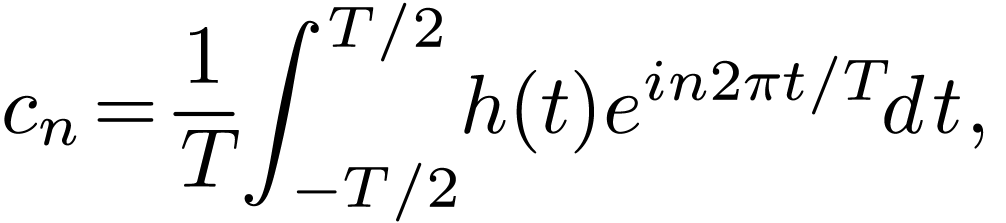

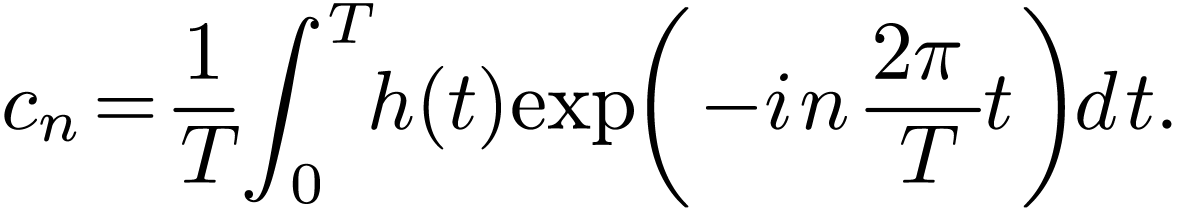

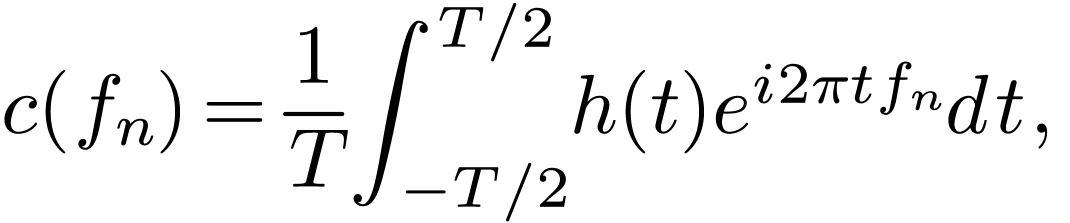

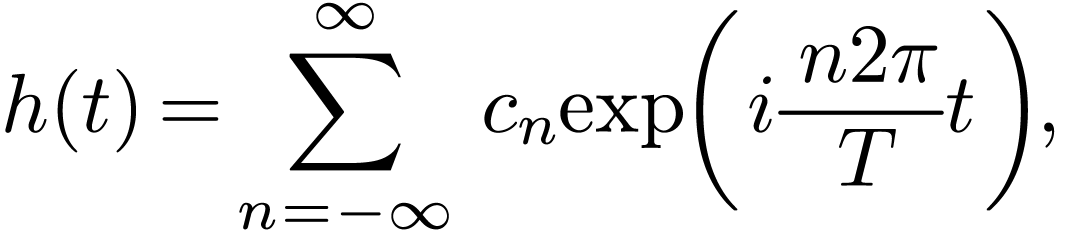

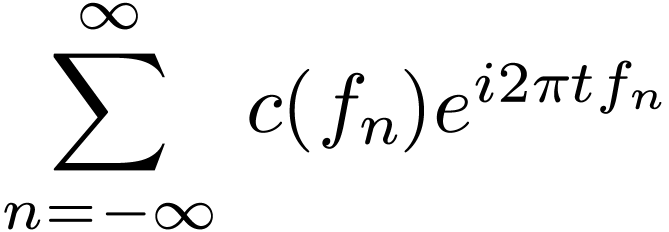

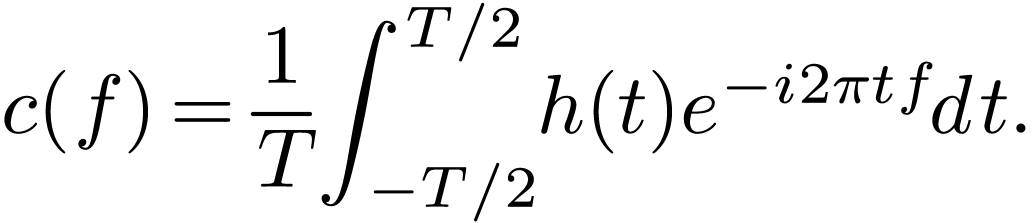

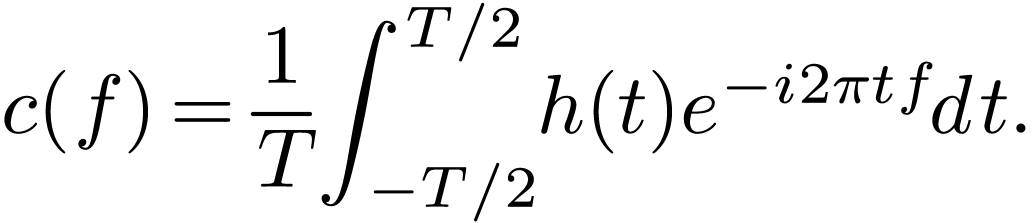

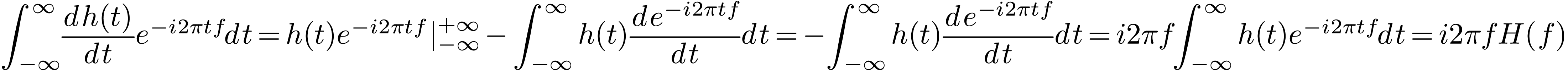

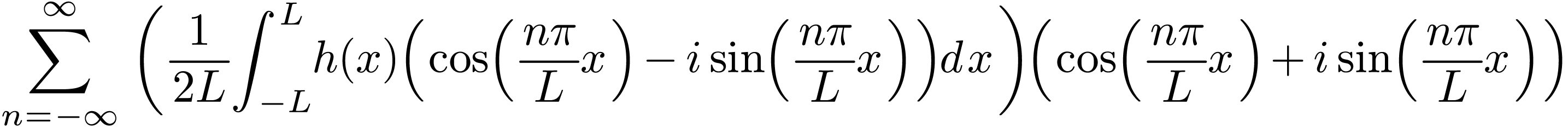

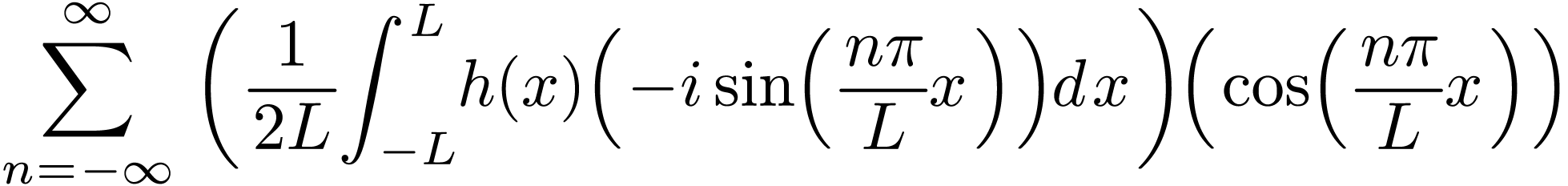

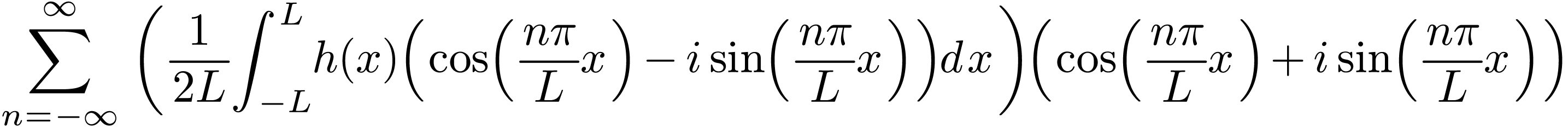

Fourier series are often expressed in terms of the complex-valued basis

functions  . Next, we derive

this version of the Fourier series, which is the most popular version we

see in textbooks and papers (we will see why this version is popular).

. Next, we derive

this version of the Fourier series, which is the most popular version we

see in textbooks and papers (we will see why this version is popular).

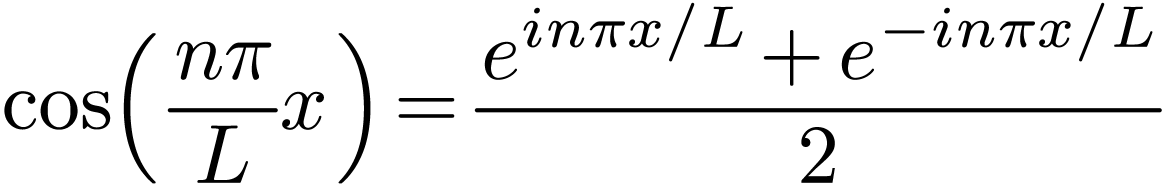

Using Euler's formula

|

(10) |

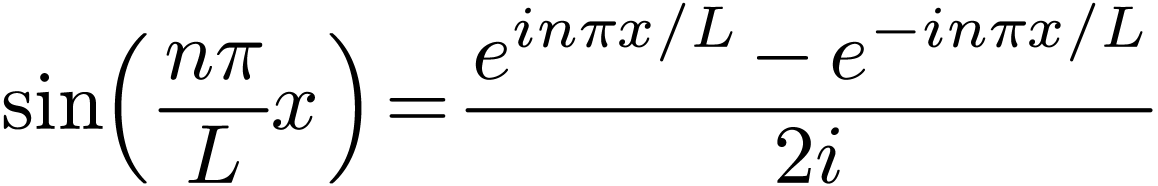

and

|

(11) |

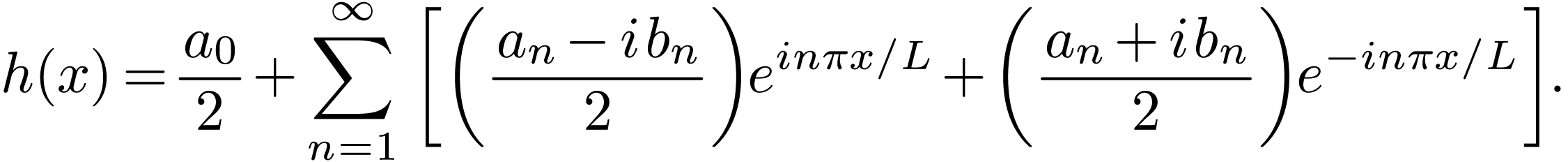

in Eq. (5), we obtain

|

(12) |

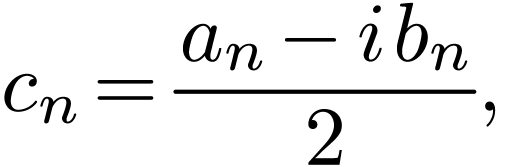

Define

|

(13) |

then, by using

,

we know that

,

we know that

|

(14) |

Then, noting  , Eq. (12)

is written

, Eq. (12)

is written

|

(15) |

Using the expressions of  and

and  given by Eq. (3) and (4),

given by Eq. (3) and (4),  is expressed as

is expressed as

|

(16) |

Equation (15) along with Eq. (16) is the

version of Fourier series using complex basis functions. In this

version, the index  is an integer ranging from

is an integer ranging from

to

to  ,

which is unlike Eq. (1), where

,

which is unlike Eq. (1), where  is

from 0 to

is

from 0 to  . An advantage of

Eqs. (15) and (16) is that no special

treatment is needed for the edge case of

. An advantage of

Eqs. (15) and (16) is that no special

treatment is needed for the edge case of  .

.

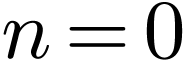

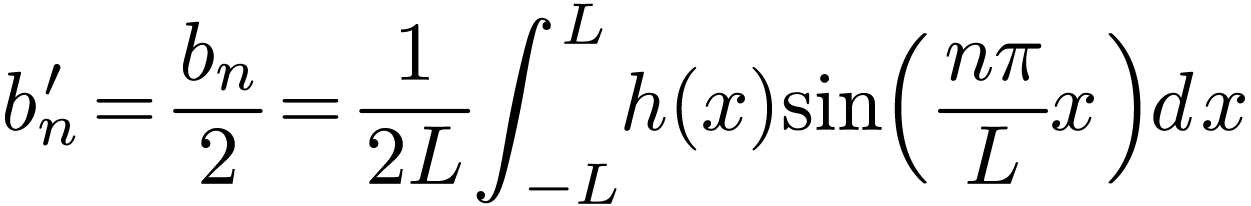

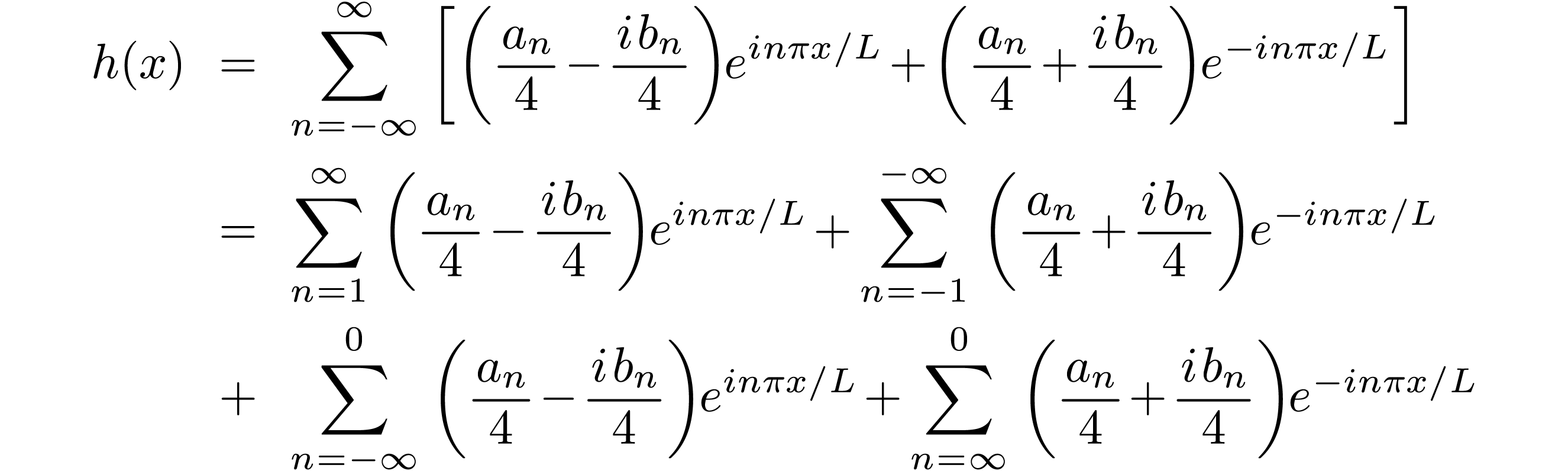

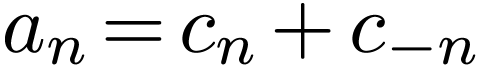

Let's recover the trigonometric version from the complex version. Using Eq. (16) in Eqs. (15), we obtain

Noting that the  terms cancel the

terms cancel the  terms in both line (17) and line (18),

the above expression is reduced to

terms in both line (17) and line (18),

the above expression is reduced to

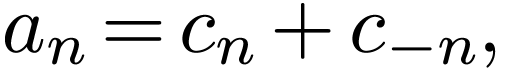

Define new expansion coefficients

|

(20) |

and

|

(21) |

then expression (19) is written as

|

(22) |

which recovers expression (6). Note that  in this version, which differs from Eq. (5). Also this

expression has no edge case that needs special treatment.

in this version, which differs from Eq. (5). Also this

expression has no edge case that needs special treatment.

As a benchmark, we can start from exression (6) to derive the complex Fourier expansion: Using the Euler formula in expression (6), we obtain

Noting that  and

and  ,

the above expresion is written as

,

the above expresion is written as

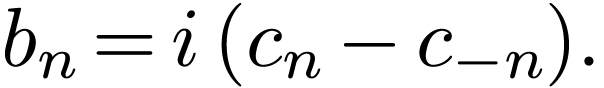

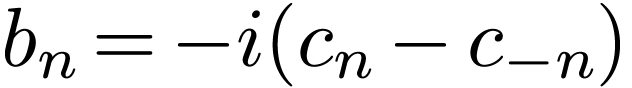

Using Eq. (13), the coefficients  and

and  appearing in Eq. (5) can be

recovered from

appearing in Eq. (5) can be

recovered from  by

by

|

(23) |

|

(24) |

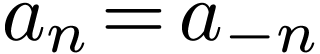

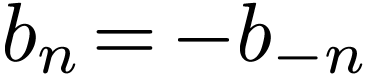

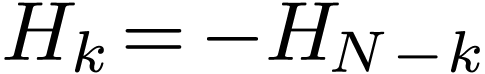

If  is real, then the coefficients

is real, then the coefficients  and

and  are real. Then Eqs. (13)

and (14) imply that

are real. Then Eqs. (13)

and (14) imply that  and

and  are complex conjugates. In this case, expressions (23) and (24) are simplified as

are complex conjugates. In this case, expressions (23) and (24) are simplified as

|

(25) |

|

(26) |

[In the above, we use the basis functions  to

expand

to

expand  . If we choose the

basis functions to be

. If we choose the

basis functions to be  , then

it is ready to verify that the Fourier series are written

, then

it is ready to verify that the Fourier series are written

|

(27) |

with  given by

given by

|

(28) |

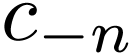

In this case, the coefficients  and

and  can be recovered from

can be recovered from  by

by

|

(29) |

|

(30) |

In using the Fourier series, we should be aware of which basis functions are used.]

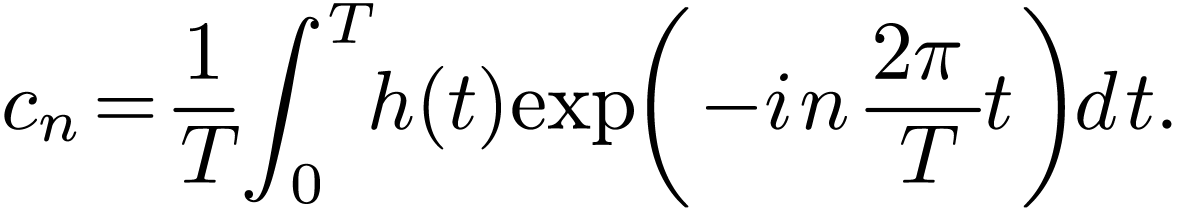

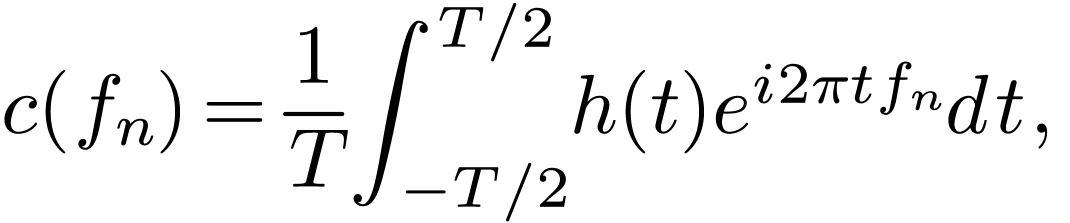

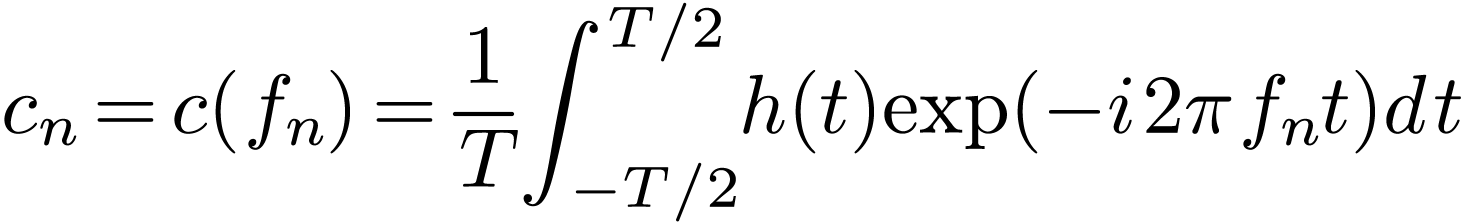

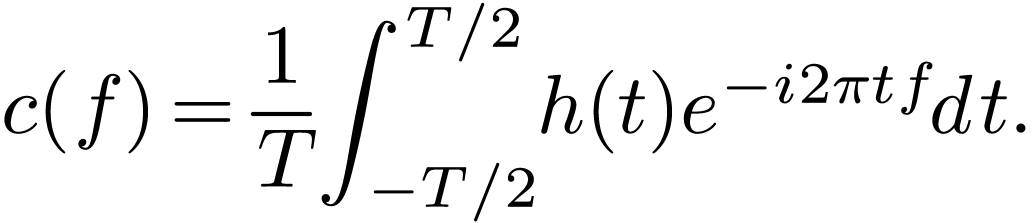

For a periodic function  with a period of

with a period of  , its Fourier expansion is given by

, its Fourier expansion is given by

|

(31) |

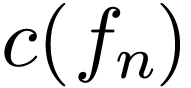

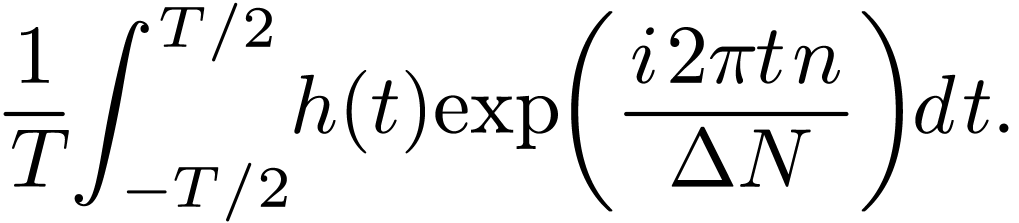

with the expansion coefficient  given by

given by

|

(32) |

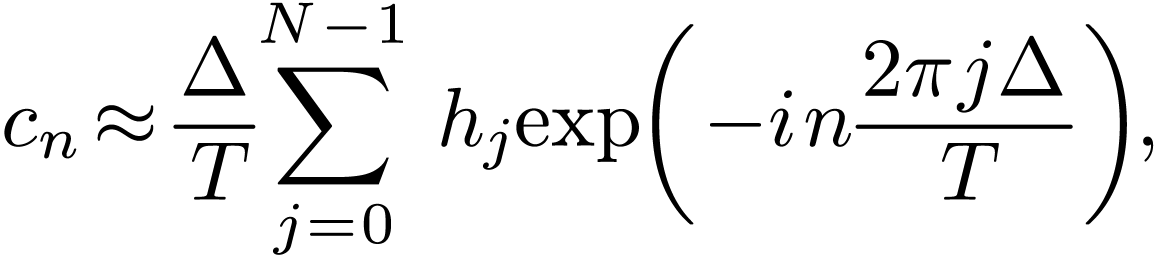

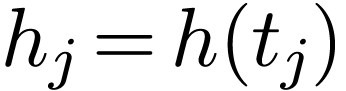

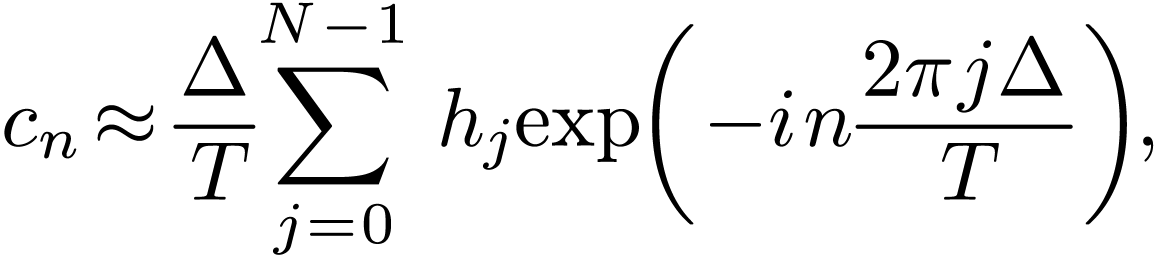

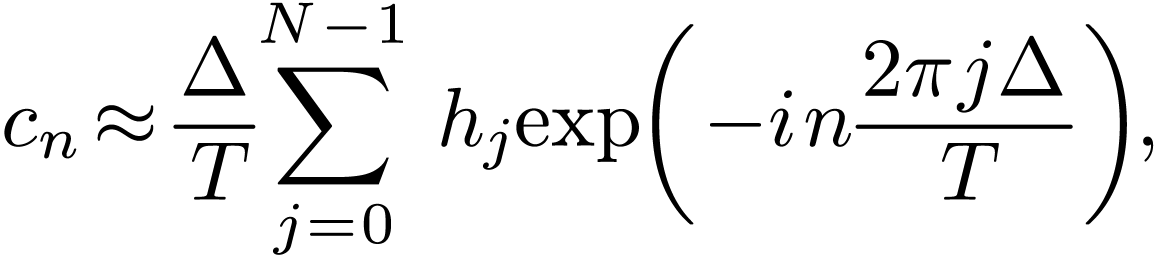

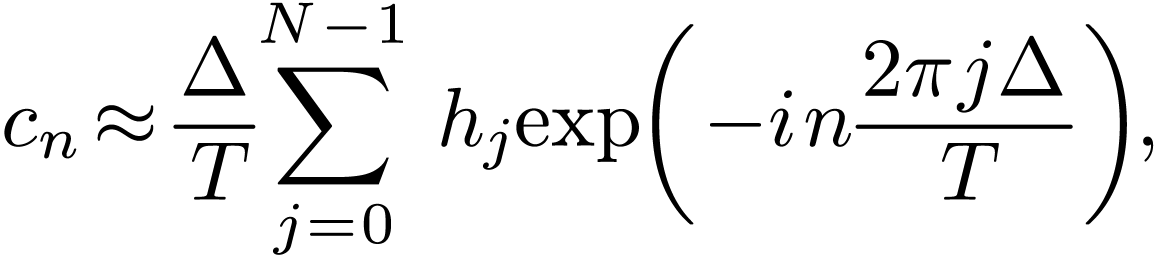

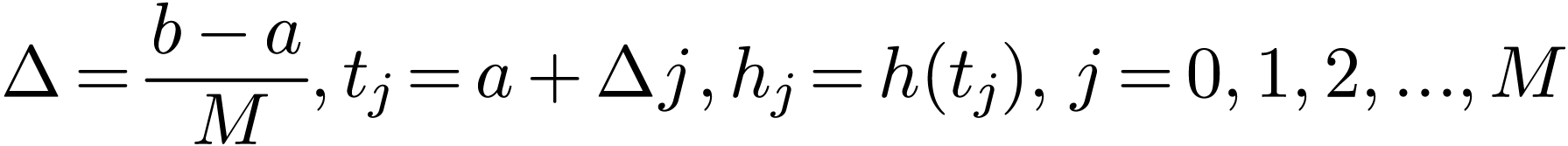

How to numerically compute  ?

A simple way is to use the rectangle formula to approximate the

integration in Eq. (32), i.e.,

?

A simple way is to use the rectangle formula to approximate the

integration in Eq. (32), i.e.,

|

(33) |

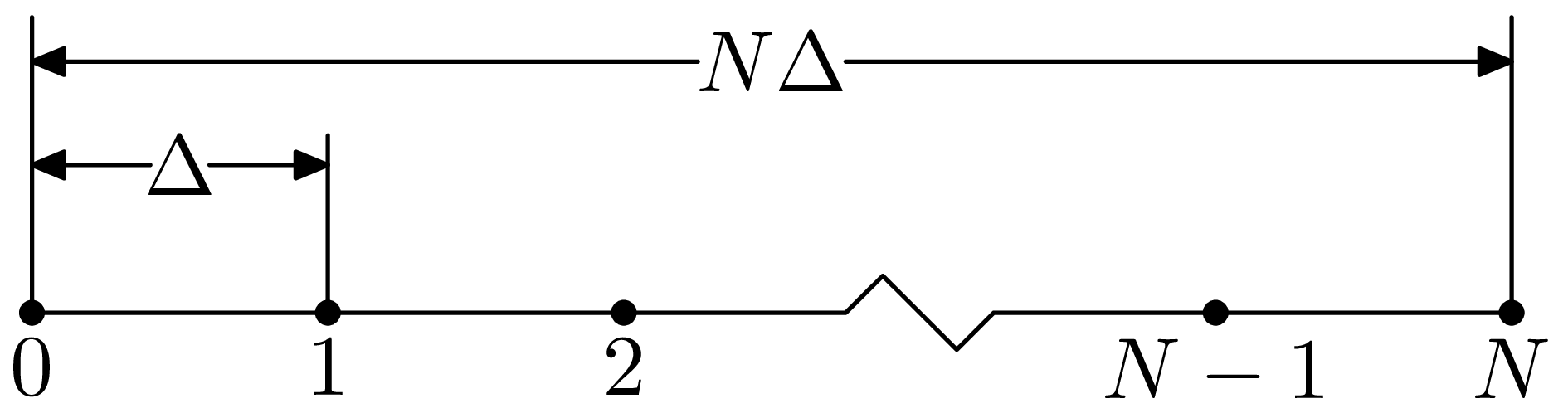

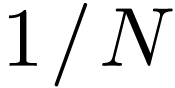

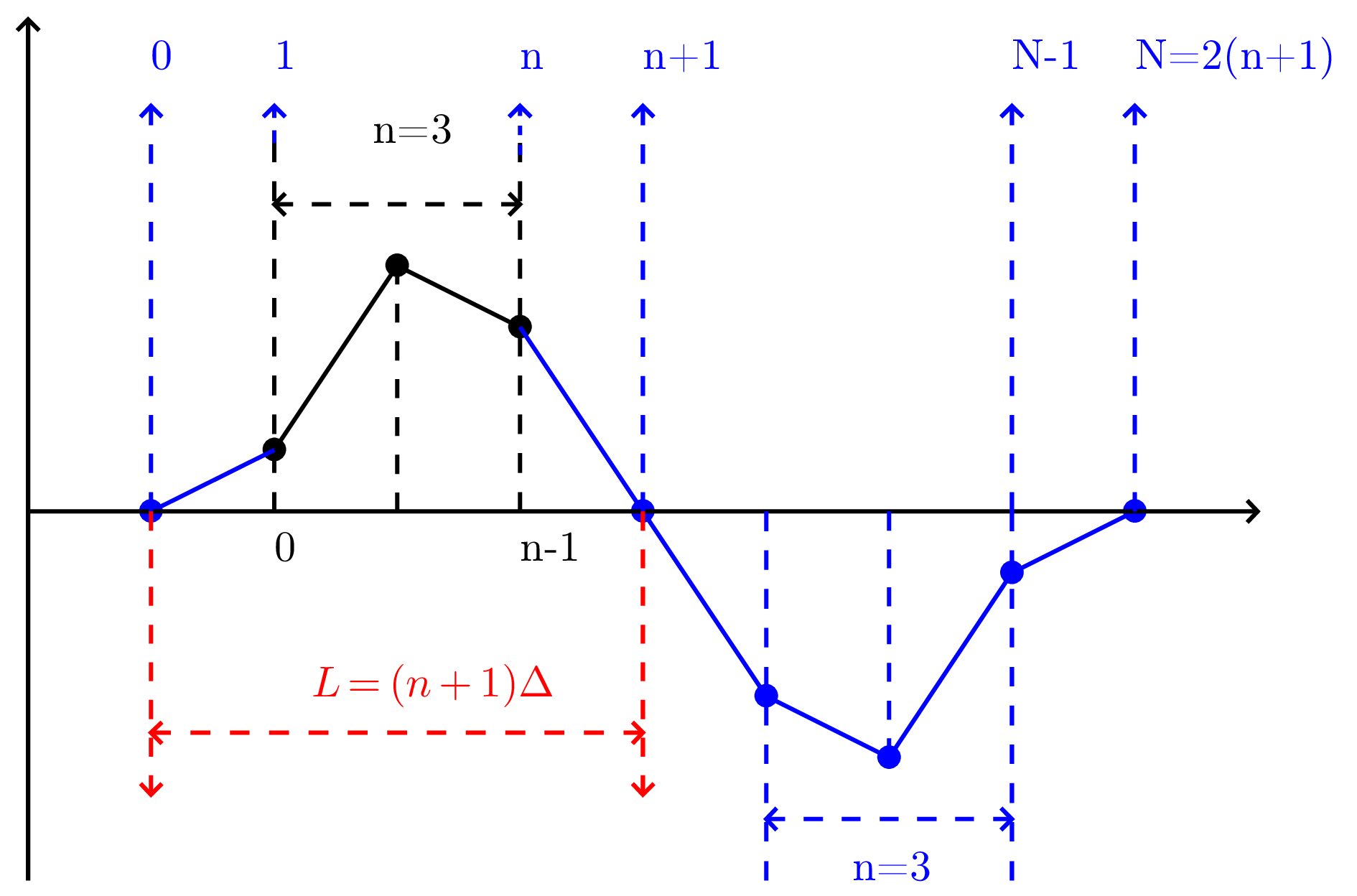

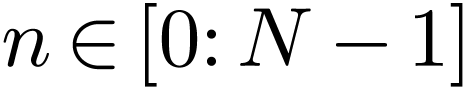

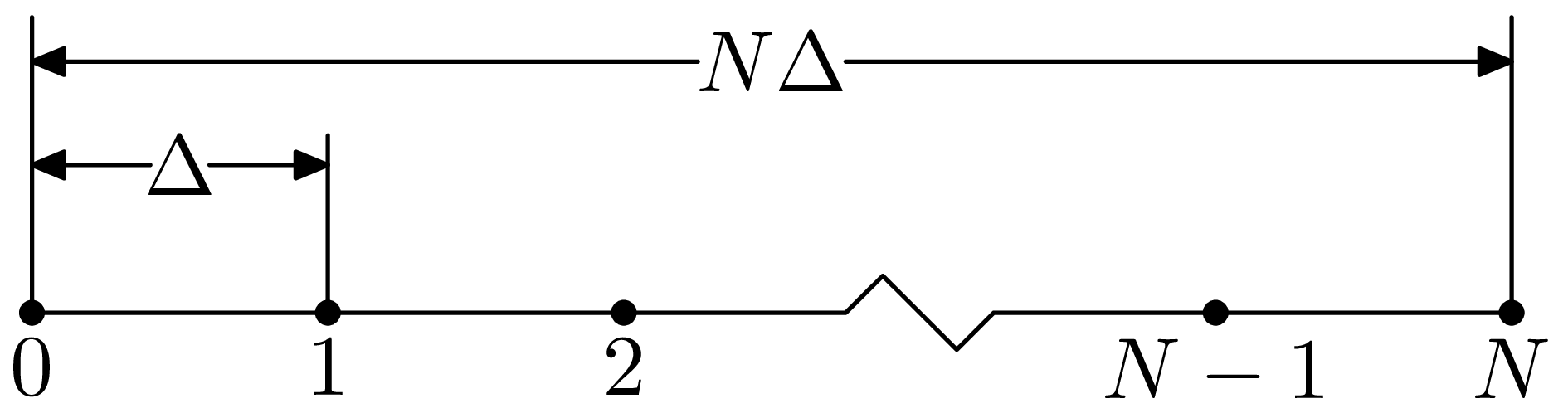

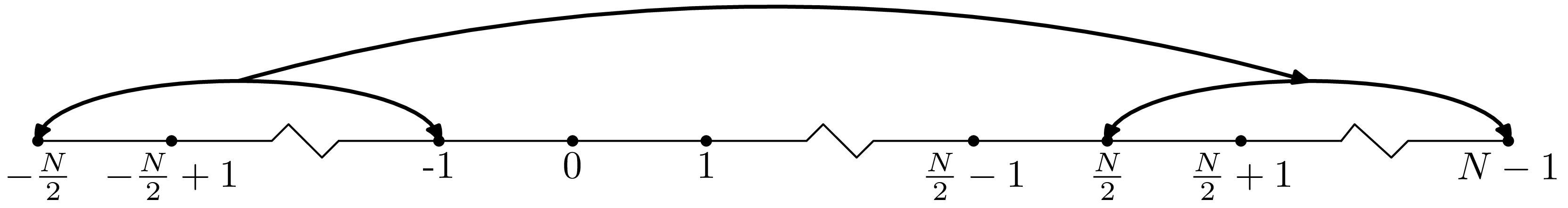

where  and

and  with

with  and

and  , as is

shown in Fig. 1.

, as is

shown in Fig. 1.

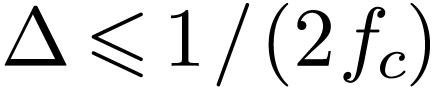

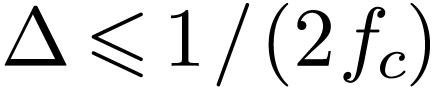

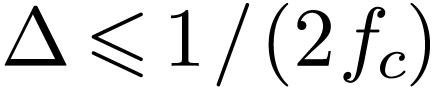

Note Eq. (33) is an approximation, which will become exact

if  . In practice, we can

sample

. In practice, we can

sample  only with a nonzero

only with a nonzero  . Therefore Eq. (33) is usually an

approximation. Do we have some rules to choose a suitable

. Therefore Eq. (33) is usually an

approximation. Do we have some rules to choose a suitable  so that Eq. (33) can become a good

approximation or even an exact relation? This important question is

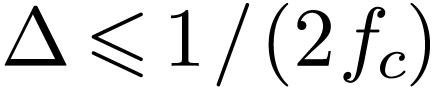

answered by the sampling theorem (will be discussed in Append. B),

which sates that a suitable

so that Eq. (33) can become a good

approximation or even an exact relation? This important question is

answered by the sampling theorem (will be discussed in Append. B),

which sates that a suitable  to

make Eq. (33) exact is given by

to

make Eq. (33) exact is given by  , where

, where  is the largest

frequency contained in

is the largest

frequency contained in  (i.e,

(i.e,  is zero for

is zero for  ).

).

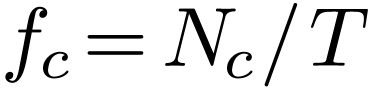

is called sampling frequency. Then the above

condition can be rephrased as: the sampling frequency should be larger

than

is called sampling frequency. Then the above

condition can be rephrased as: the sampling frequency should be larger

than  .

.

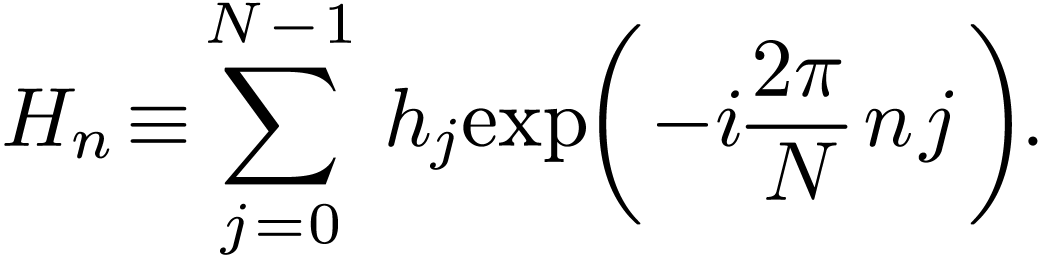

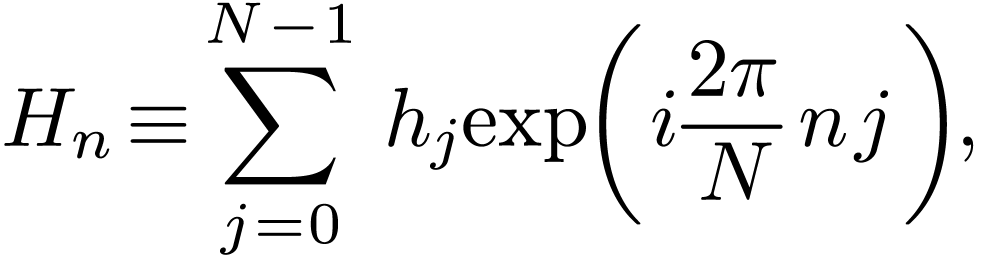

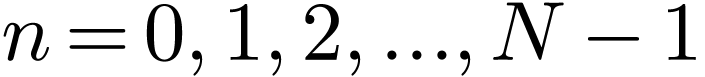

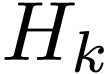

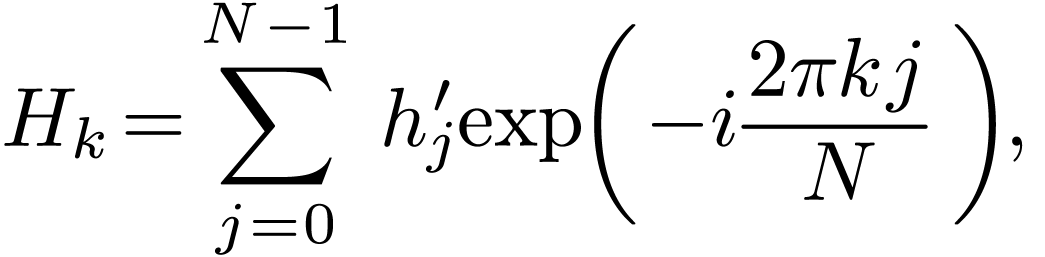

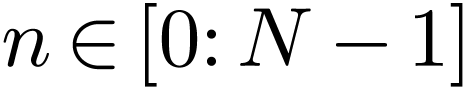

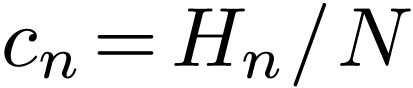

Denote the summation in Eq. (33) by  :

:

|

(34) |

Then  with

with  is the

Discrete Fourier transformation (DFT) of

is the

Discrete Fourier transformation (DFT) of  with

with  . (The

efficient algorithm (FFT) of computing the DFT is discussed in Appendix

A.)

. (The

efficient algorithm (FFT) of computing the DFT is discussed in Appendix

A.)

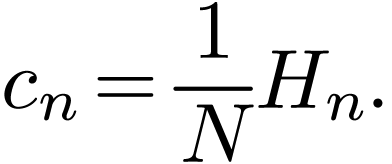

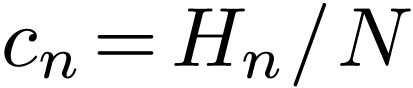

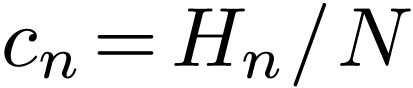

The Fourier expansion coefficients  in Eq. (33) is related to

in Eq. (33) is related to  by

by

|

(35) |

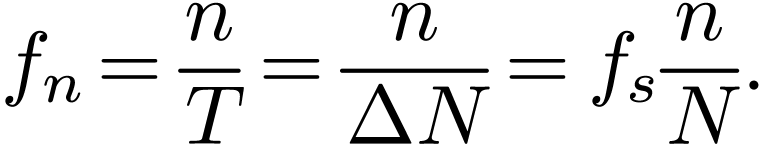

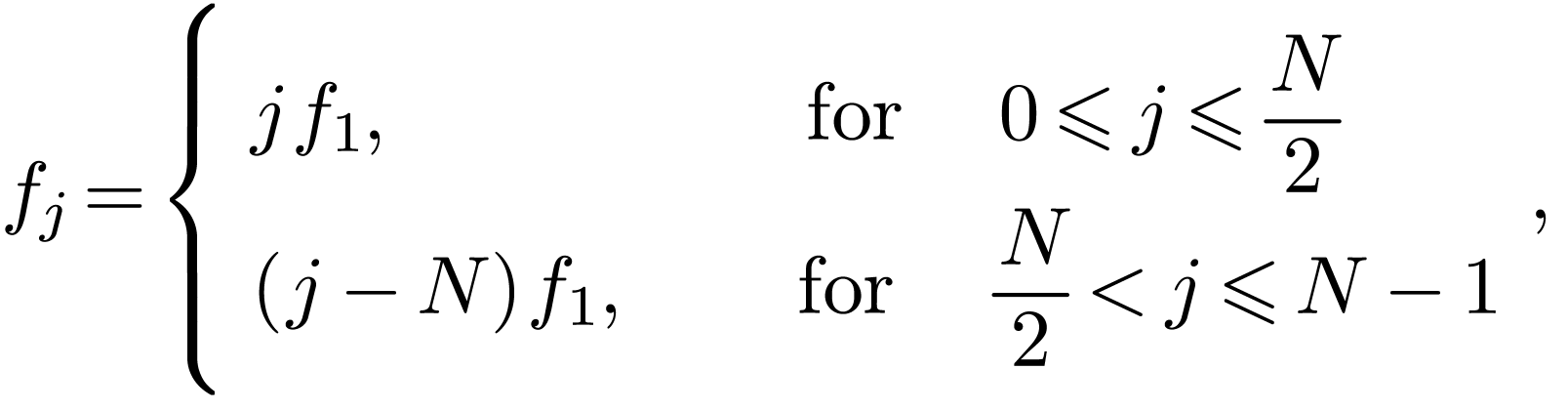

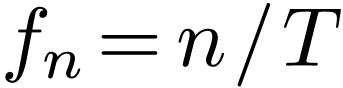

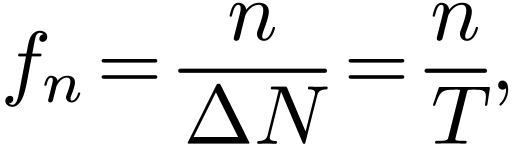

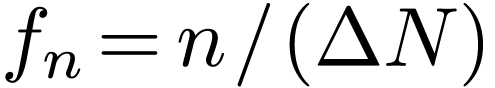

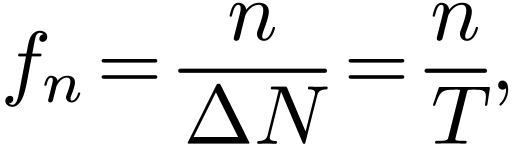

The corresponding frequency is

|

(36) |

Here  is called the fundamental frequency

(spacing in the frequency domain, i.e., frequency resolution).

is called the fundamental frequency

(spacing in the frequency domain, i.e., frequency resolution).

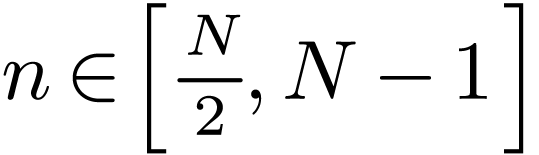

Why does DFT choose  to be in the positive range

to be in the positive range

? This is to make the

tranform pair symmetric: both

? This is to make the

tranform pair symmetric: both  and

and  are in the same range. This symmetry makes the transform

pair easy to remember. However, this does not mean we only need the

positive frequency components. In fact, we usually need

are in the same range. This symmetry makes the transform

pair easy to remember. However, this does not mean we only need the

positive frequency components. In fact, we usually need  in the range

in the range  . This will be

discussed in the next section.

. This will be

discussed in the next section.

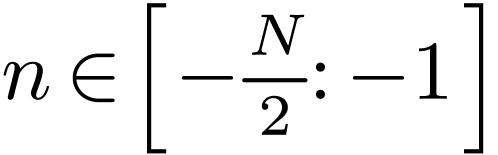

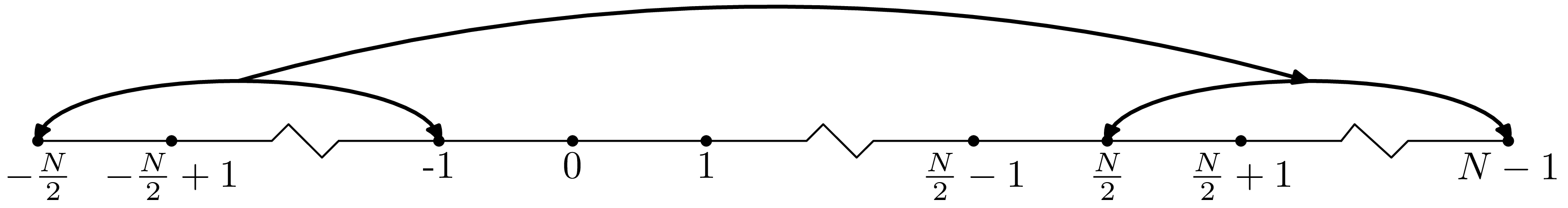

We are usually interested in Fourier expansion coefficients in the range

(assume that

(assume that  is even)

because we expect the coefficients decay with

is even)

because we expect the coefficients decay with  increasing (so we impose a cutoff for a range that is symmetric about

increasing (so we impose a cutoff for a range that is symmetric about

). However, the original DFT

is for the range

). However, the original DFT

is for the range  . How do we

reconcile them? The answer is that we make use of the periodic property

of DFT. It is obvious that

. How do we

reconcile them? The answer is that we make use of the periodic property

of DFT. It is obvious that  defined in Eq. (34) has the following periodic property:

defined in Eq. (34) has the following periodic property:

|

(37) |

Using this, we can infer what we need: the value of each  with

with  is equal to

is equal to  with

with  , element by element.

Then we can associate

, element by element.

Then we can associate  for

for  with frequency

with frequency  defined by:

defined by:

|

(38) |

The frequency interval between neighbor DFT points is  , where

, where  is the

time-window in which the signal is sampled. This frequency interval is

called frequency resolution (resolution in the frequency domain), which

is determined only by the length of the time-window and is independent

of the sampling frequency. If the time-window is fixed, increasing the

sampling frequency only increase the frequency range of the DFT (

is the

time-window in which the signal is sampled. This frequency interval is

called frequency resolution (resolution in the frequency domain), which

is determined only by the length of the time-window and is independent

of the sampling frequency. If the time-window is fixed, increasing the

sampling frequency only increase the frequency range of the DFT ( ), which is called bandwidth, and

the frequency interval between neighbor DFT points are still

), which is called bandwidth, and

the frequency interval between neighbor DFT points are still  , i.e., the frequency resolution is

not changed.

, i.e., the frequency resolution is

not changed.

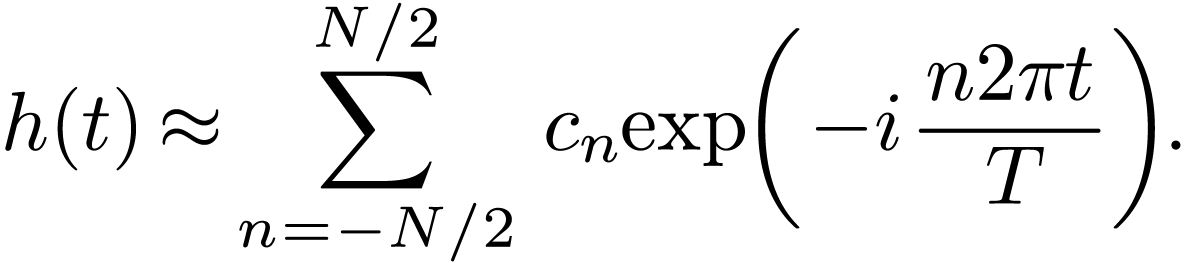

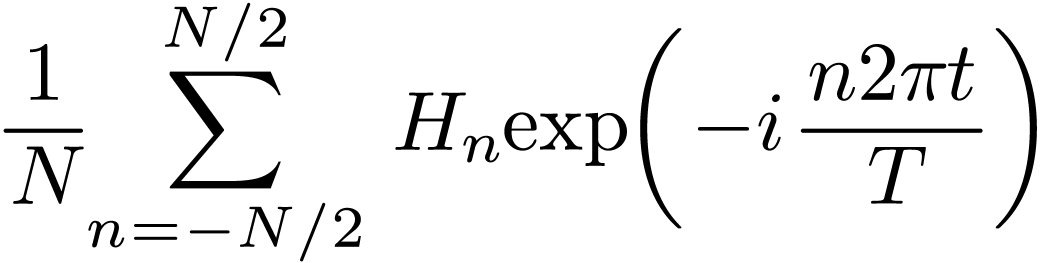

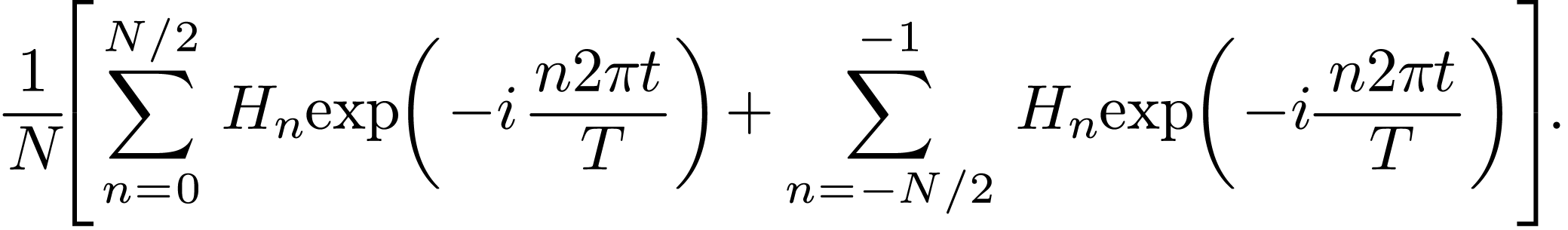

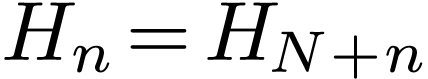

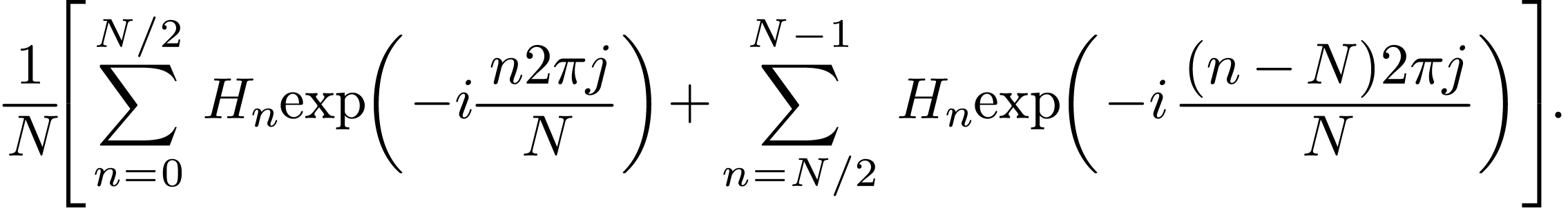

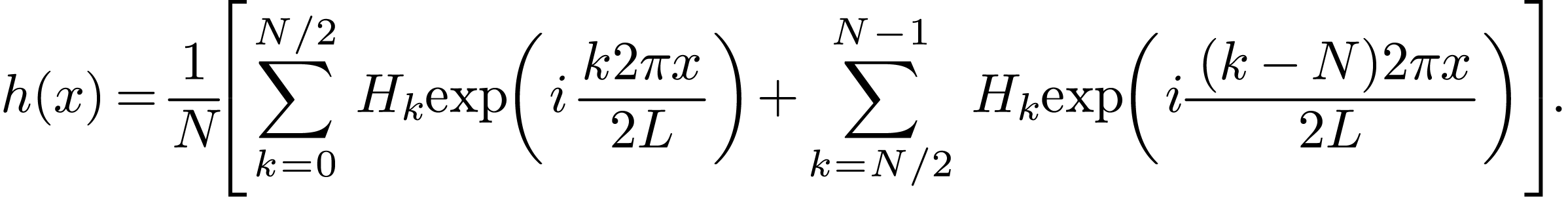

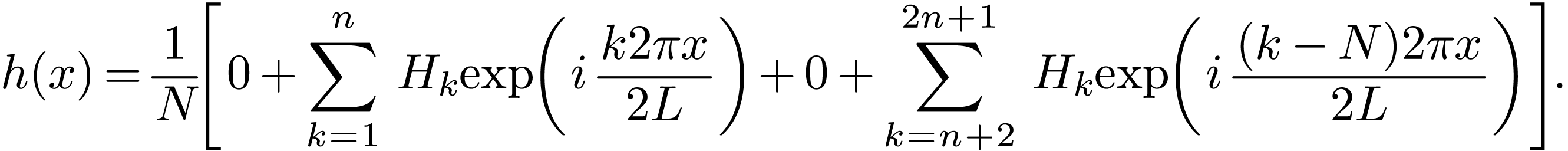

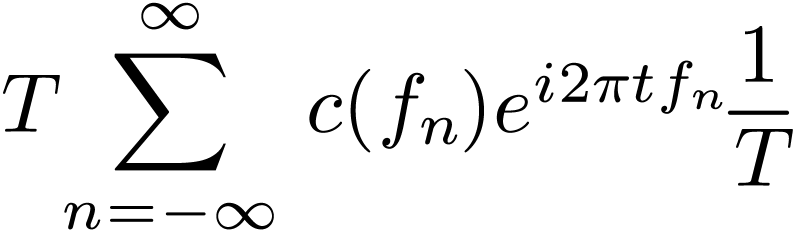

The Fourier series of

|

(39) |

can be approximated as

|

(40) |

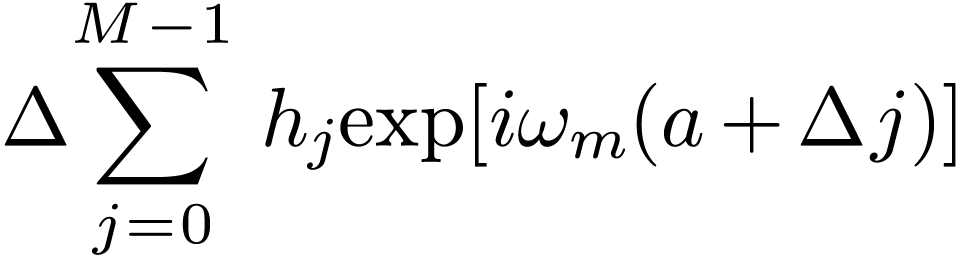

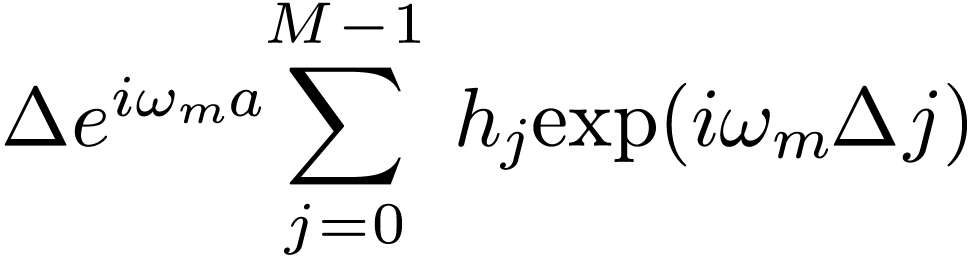

Using the relation  , the

above equation is written as

, the

above equation is written as

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Using the periodic property of DFT, i.e.,  ,

the above expression is written as

,

the above expression is written as

Equation (42) provides a formula of constructing an approximate function using the DFT of the discrete samplings of the original function.

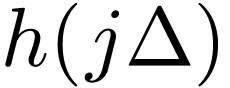

Evaluate  given by Eq. (42) at the

discrete point

given by Eq. (42) at the

discrete point  , yielding

, yielding

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

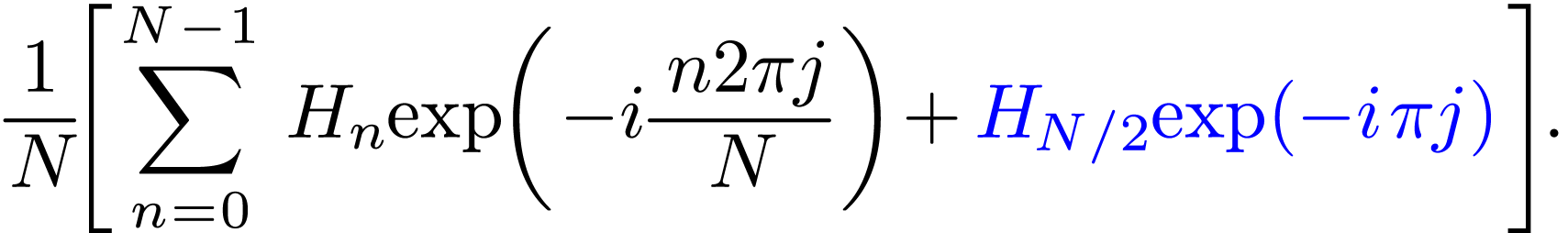

Drop the blue term (which is negligible if  satisfies the condition requried by the sampling theorem),

then

satisfies the condition requried by the sampling theorem),

then  is written as

is written as

|

(44) |

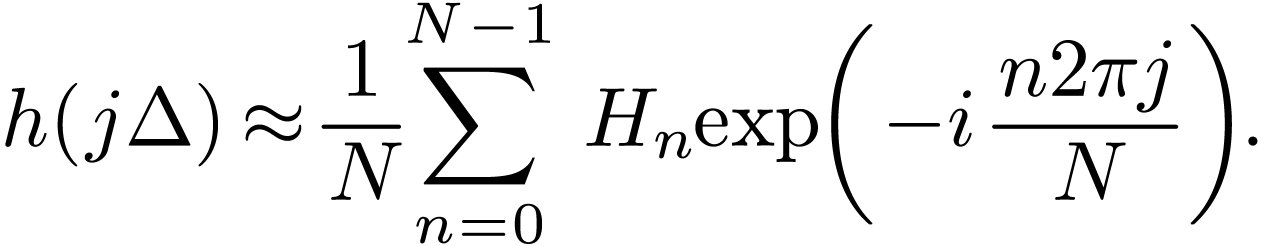

The right-hand side of Eq. (44) turns out to be the inverse DFT discussed in Sec. 4.3.

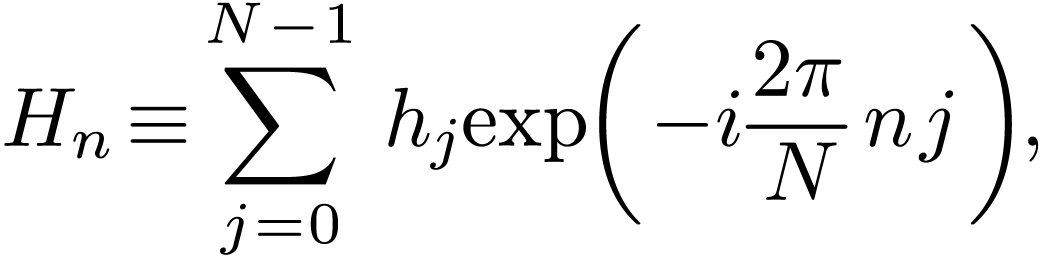

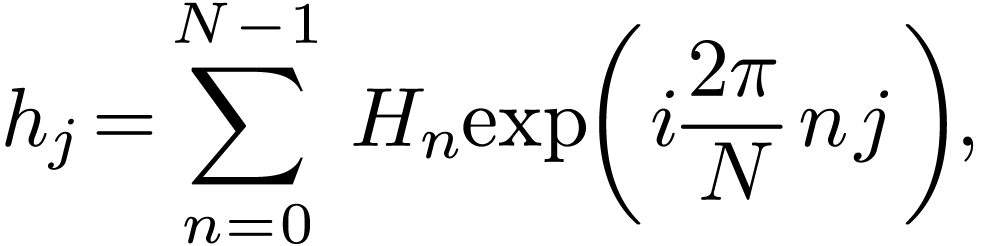

The DFT in Eq. (34), i.e.,

|

(45) |

with  and

and  can also be

considered as a set of linear algebraic equations for

can also be

considered as a set of linear algebraic equations for  and can be solved in terms of

and can be solved in terms of  ,

which gives

,

which gives

|

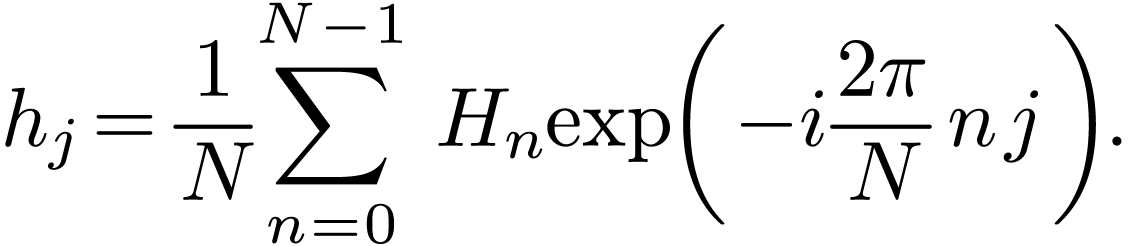

(46) |

(The details on how to solve Eq. (34) to obtain the

solution (46) is provided in Sec. 4.4.)

Equation (46) recovers  from

from  (i.e., the DFT of

(i.e., the DFT of  ),

and thus is called the inverse DFT.

),

and thus is called the inverse DFT.

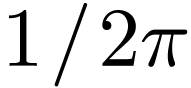

The normalization factor multiplying the DFT and inverse DFT (here  and

and  ) and

the signs of the exponents are merely conventions. The only requirement

is that the DFT and inverse DFT have opposite-sign exponents and that

the product of their normalization factors be

) and

the signs of the exponents are merely conventions. The only requirement

is that the DFT and inverse DFT have opposite-sign exponents and that

the product of their normalization factors be  . In most FFT computer libraries, the

. In most FFT computer libraries, the  factor is omitted. So one must manually include this

factor when one wants to reproduce the original data by a forward and

then a backward transform.

factor is omitted. So one must manually include this

factor when one wants to reproduce the original data by a forward and

then a backward transform.

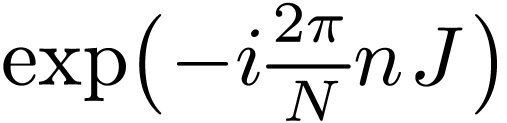

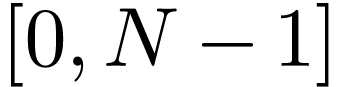

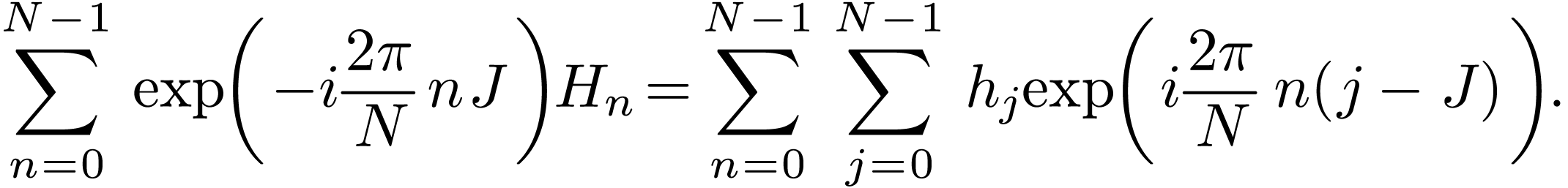

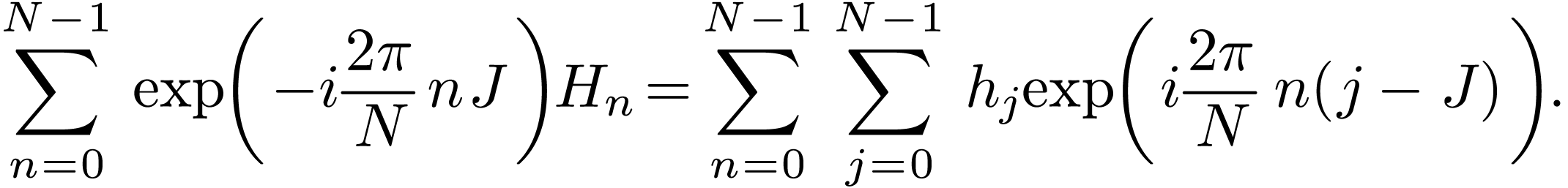

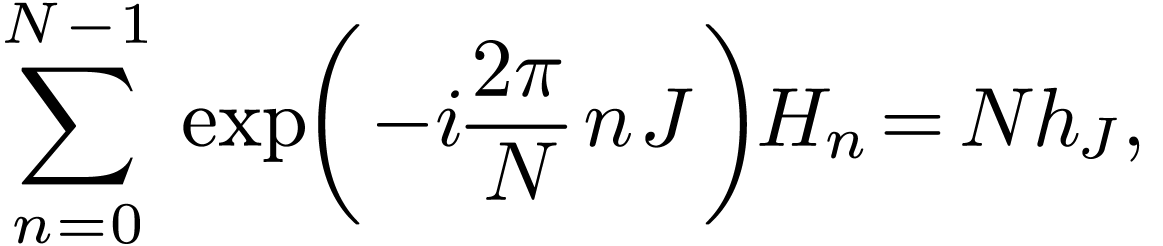

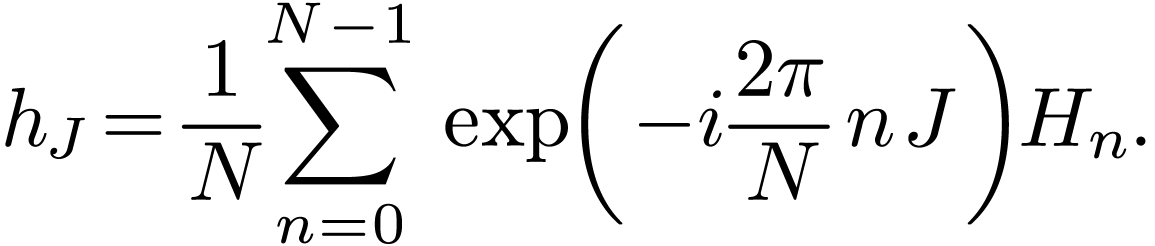

In order to solve the linear algebraic equations (34) for

, multiply both sides of each

equation by

, multiply both sides of each

equation by  , where

, where  is an integer between

is an integer between  ,

and then add all the equations together, which yields

,

and then add all the equations together, which yields

|

(47) |

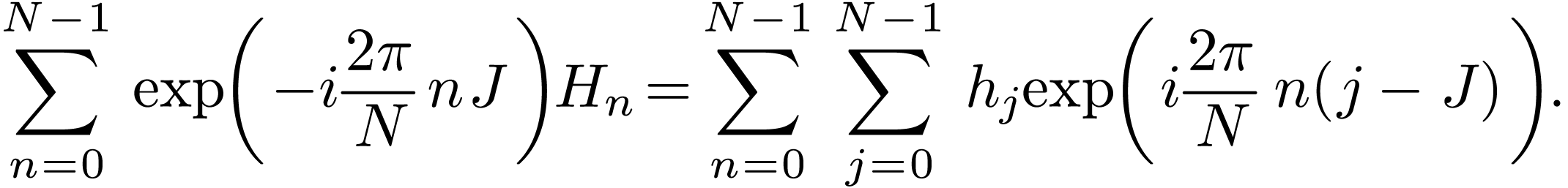

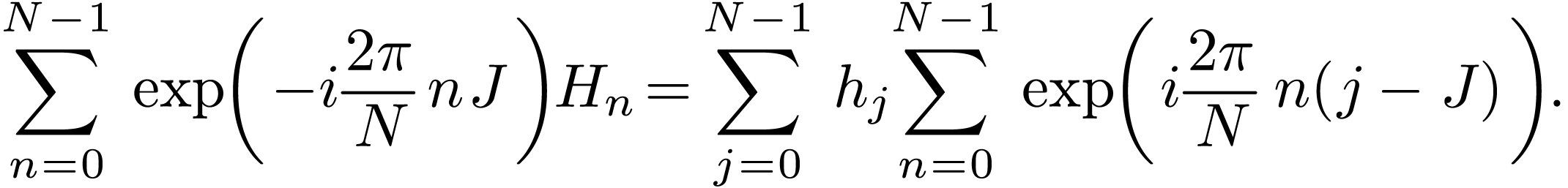

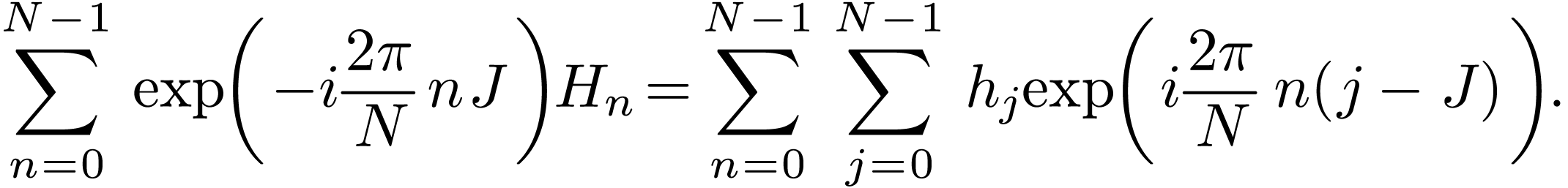

Interchanging the sequence of the two summation on the right-hand side, equation (47) is written

|

(48) |

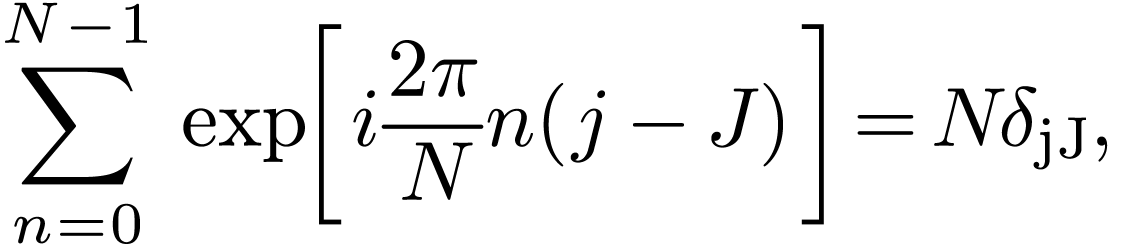

Using the fact that (verified by Wolfram Mathematica)

|

(49) |

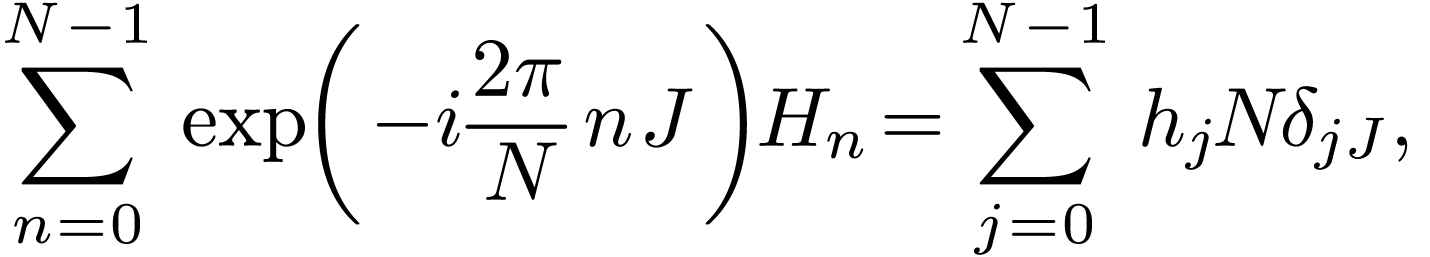

where  is the Kroneker Delta, equation (48)

is written

is the Kroneker Delta, equation (48)

is written

|

(50) |

i.e.,

|

(51) |

which can be solved to give

|

(52) |

Equation (52) is the inverse DFT.

FFTW/scipy uses negative exponents as the forward transform and and the positive exponents as inverse transform. Specifically, the forward DFT in FFTW is defined by

|

(53) |

and the inverse DFT is defined by

|

(54) |

where there is no  factor in the inverse DFT, and

thus this factor should be included manually if we want to recover the

original data from the inverse DFT. (In some rare cases, e.g. in the

book “Numerical recipe”[2], positive exponents

are used in defining the forward Fourier transformation and negative

exponents are used in defining the backward one. When using a Fourier

transformation library, it is necessary to know which convention is used

in order to correctly use the output of the library.)

factor in the inverse DFT, and

thus this factor should be included manually if we want to recover the

original data from the inverse DFT. (In some rare cases, e.g. in the

book “Numerical recipe”[2], positive exponents

are used in defining the forward Fourier transformation and negative

exponents are used in defining the backward one. When using a Fourier

transformation library, it is necessary to know which convention is used

in order to correctly use the output of the library.)

In Scipy:

def fft(x, n=None, axis=-1, norm=None, overwrite_x=False, workers=None, *,

plan=None):

#norm : {"backward", "ortho", "forward"}, optional

Normalization mode. Default is "backward", meaning no normalization on

the forward transforms and scaling by 1/n on the ifft.

"forward" instead applies the 1/n factor on the forward tranform.

For norm="ortho", both directions are scaled by 1/sqrt(n).

I use the Fortran interface of the FFTW library. To have access to FFTW library, use the following codes:

use, intrinsic :: iso_c_binding implicit none include 'fftw3.f03'

Here the first line uses iso_c_binding module to interface

with C in which FFTW is written. To use the FFT subroutines in FFTW, we

need to define some variables of the desired types, such as

type(C_PTR) :: plan1, plan2 complex(C_DOUBLE_COMPLEX) :: in(0:n-1), out(0:n-1)

Specify what kind of transform to be performed by calling the corresponding “planner” routine:

plan1 = fftw_plan_dft_1d(n, in,out, FFTW_FORWARD,FFTW_ESTIMATE)

Here the “planner” routine for one-dimensional DFT is

called. One thing that the “planner” routine does is to

factor the matrix  mentioned above, in order to

get prepared for performing the actual transform. Therefore

“planner” do not need the actual data stored in

“in” array. What is needed is the length and numerical type

of “in” array. It is obvious that the “planner”

routine needs to be invoked for only once for a given type of array with

the same length.

mentioned above, in order to

get prepared for performing the actual transform. Therefore

“planner” do not need the actual data stored in

“in” array. What is needed is the length and numerical type

of “in” array. It is obvious that the “planner”

routine needs to be invoked for only once for a given type of array with

the same length.

Store input data in the “in” arrays, then, we can perform a DFT by the following codes:

call fftw_execute_dft(plan1, in, out)

Similarly, we can perform a inverse DFT by the following codes:

plan2 = fftw_plan_dft_1d(ngrids, in,out,FFTW_BACKWARD,FFTW_ESTIMATE) call fftw_execute_dft(plan2, in, out)

After all the transforms are done, we need to manually de-allocate the arrays created by the “planner” routine by calling the “fftw_destroy_plan” routine:

call fftw_destroy_plan(plan2)

(Unless they are local arrays, Fortran does not automatically

de-allocate arrays allocated by the acllocate(), so

manually de-allocate all allocated arrays is necessary for avoid memory

leak)

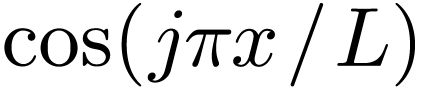

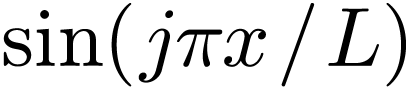

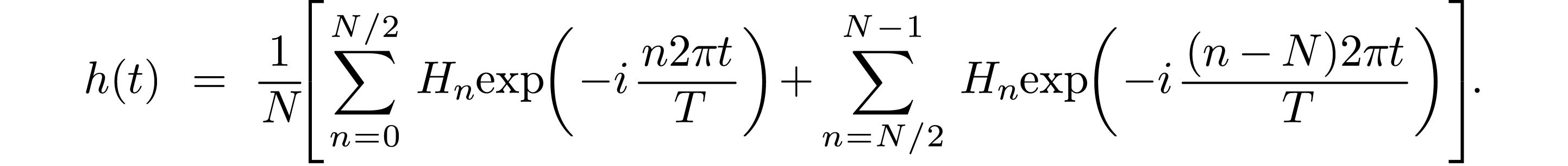

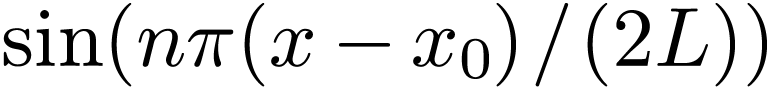

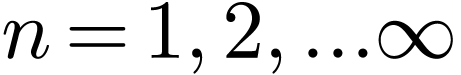

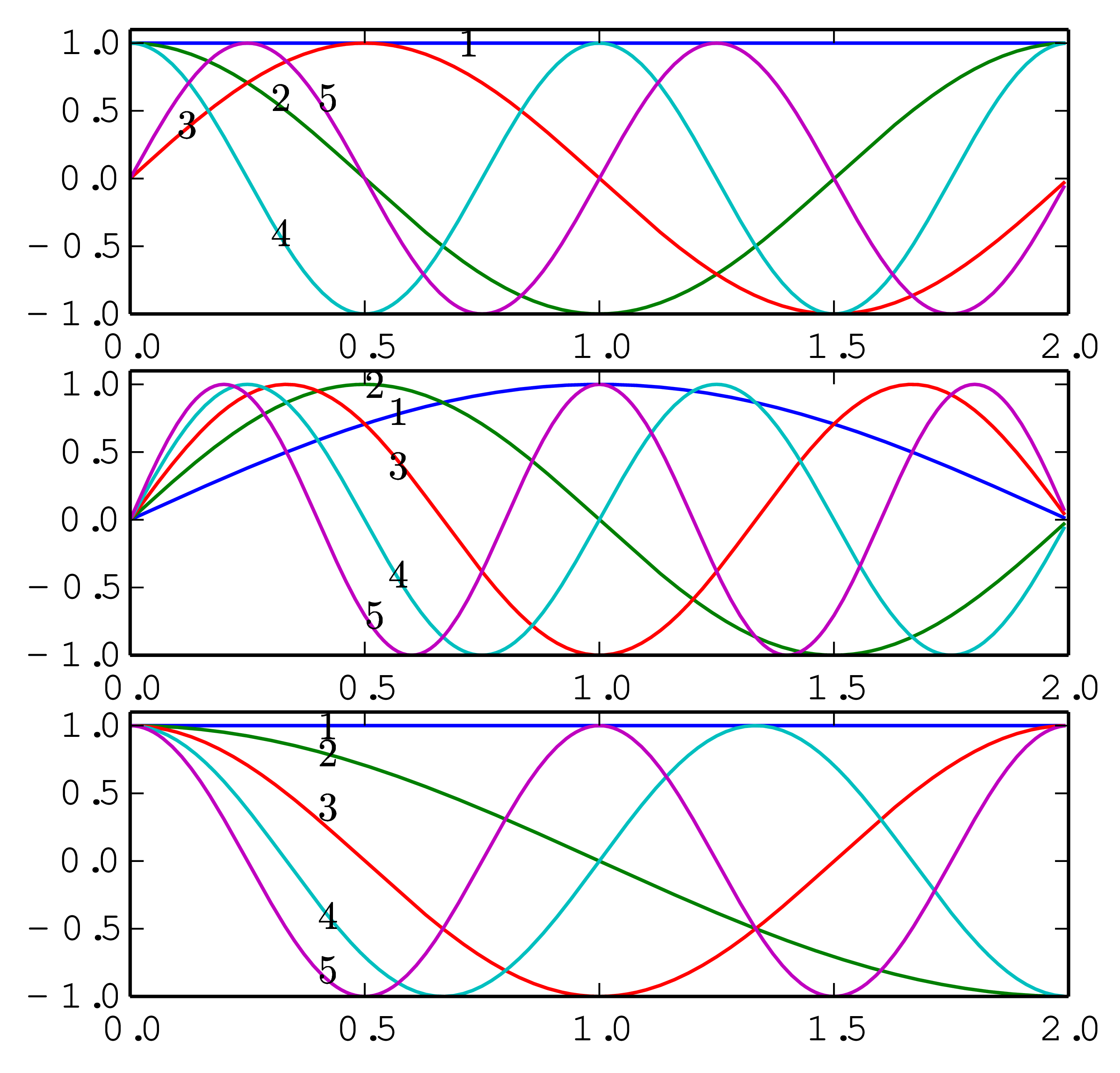

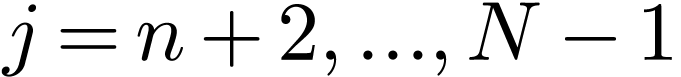

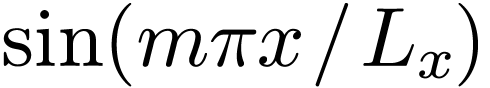

We mentioned (without giving proof) that the set of functions  and

and  with

with  is a “complete set” in expanding any function in the

interval

is a “complete set” in expanding any function in the

interval  , where

, where  is an arbitrary point. Therefore Fourier series use both

cosine and sine as basis functions to expand a function. Let us

introduce another conclusion (again without giving proof) that the set

of sine functions

is an arbitrary point. Therefore Fourier series use both

cosine and sine as basis functions to expand a function. Let us

introduce another conclusion (again without giving proof) that the set

of sine functions  with

with  is a “complete set” in expanding any function

is a “complete set” in expanding any function  in the interval

in the interval  .

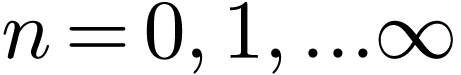

A similar conclusion is that the set of cosine functions

.

A similar conclusion is that the set of cosine functions  with

with  is a “complete

set” in expanding any function

is a “complete

set” in expanding any function  in the

interval

in the

interval  . Note that the

argument of the basis functions used in the Fourier expansion differ

from those used in the sine/cosine expansion by a factor of two.

. Note that the

argument of the basis functions used in the Fourier expansion differ

from those used in the sine/cosine expansion by a factor of two.

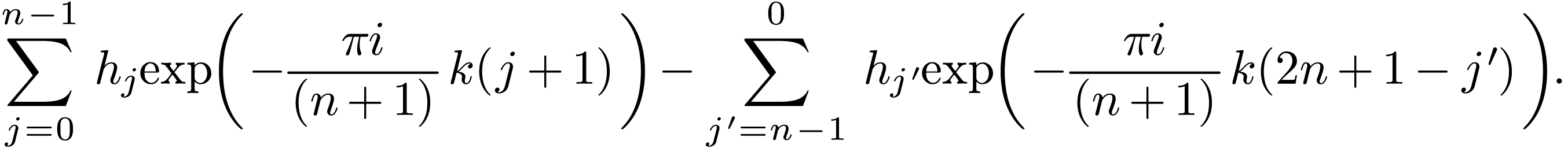

The first five basis functions used in Fourier expansion, sine expansion, and cosine expansion are plotted in Fig. 2.

|

The basis function  used in the Fourier expansion

have the properties

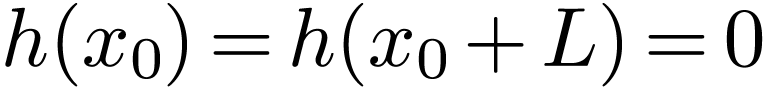

used in the Fourier expansion

have the properties  .

Therefore Fourier expansion works best for function that satisfy

.

Therefore Fourier expansion works best for function that satisfy  . For a functions that do not

satisfies this condition, i.e., a function with

. For a functions that do not

satisfies this condition, i.e., a function with  , the function can still be considered as a periodic

function with period

, the function can still be considered as a periodic

function with period  but having discontinuity

points at the interval boundary. It is well known that Gibbs

oscillations appear near discontinuity points, which can be inner points

in the interval or at the interval boundaries.

but having discontinuity

points at the interval boundary. It is well known that Gibbs

oscillations appear near discontinuity points, which can be inner points

in the interval or at the interval boundaries.

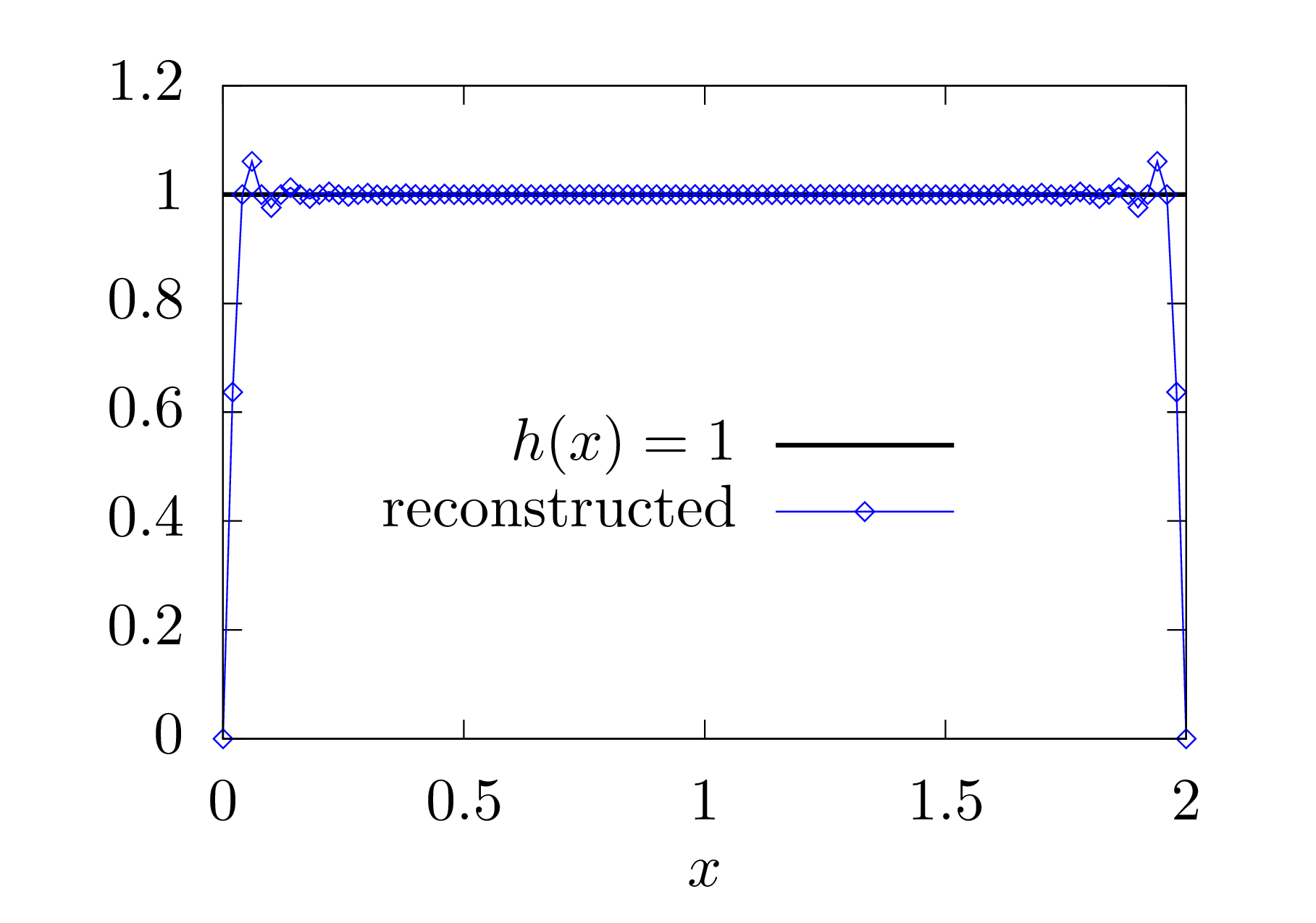

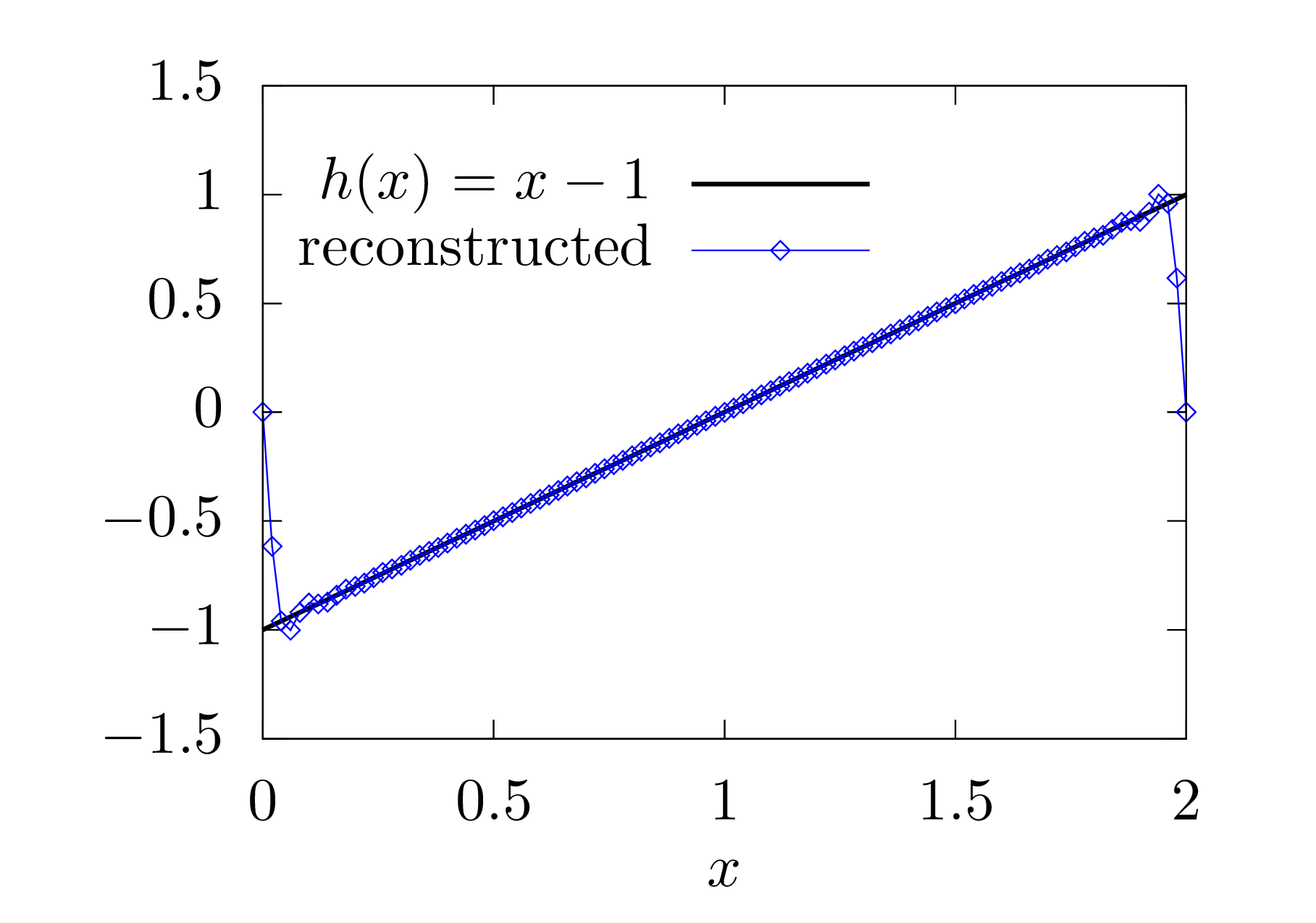

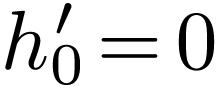

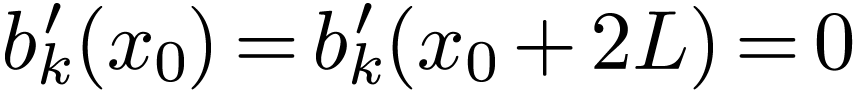

The basis functions  used in the sine expansion

have the properties

used in the sine expansion

have the properties  .

Therefore this expansion works best for functions that satisfy

.

Therefore this expansion works best for functions that satisfy  . For functions that do not

satisfies this condition, there will be Gibbs oscillations near the

boundaries when approximated by using the sine expansion. Examples are

shown in Fig. 3.

. For functions that do not

satisfies this condition, there will be Gibbs oscillations near the

boundaries when approximated by using the sine expansion. Examples are

shown in Fig. 3.

|

Figure 3. Left: constant function

|

Similarly, the basis functions  used in the

cosine expansion have the properties

used in the

cosine expansion have the properties  .

Therefore this expansion works best for functions that satisfy

.

Therefore this expansion works best for functions that satisfy  . For functions that do not

satisfies this condition, there will be Gibbs oscillations near the

boundaries when approximated by using the cosine expansion (to be

verified numerically).

. For functions that do not

satisfies this condition, there will be Gibbs oscillations near the

boundaries when approximated by using the cosine expansion (to be

verified numerically).

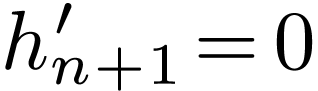

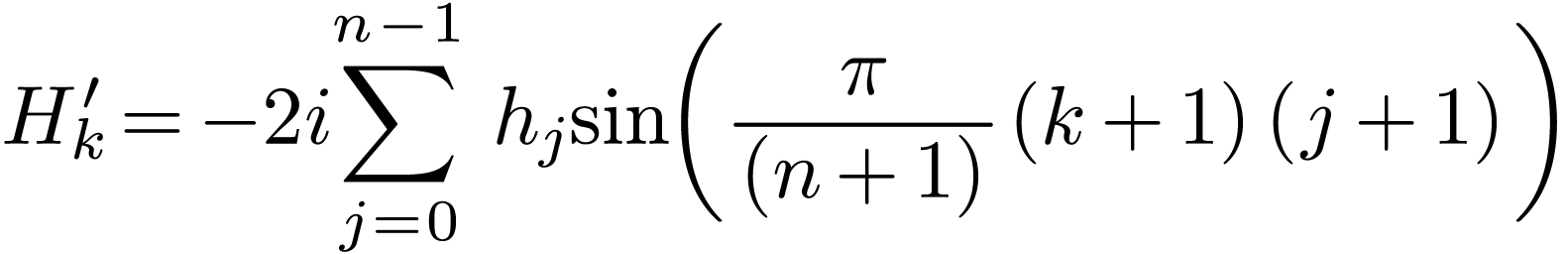

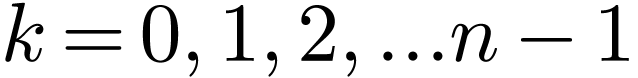

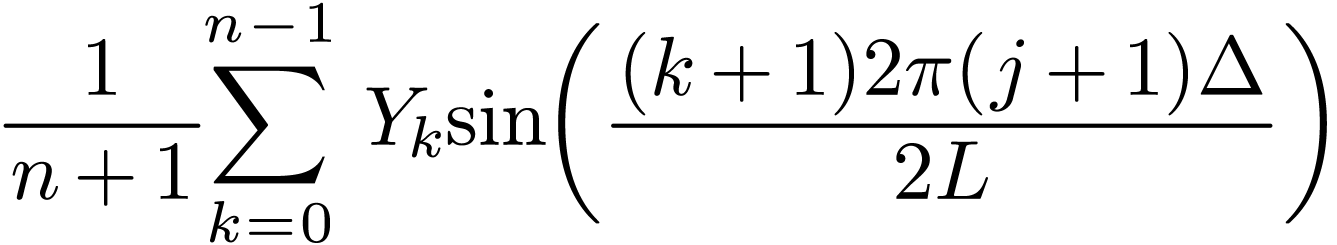

Next, let us discuss the sine and cosine transformation. Figure 4 illustrates the grids used in the following discussion.

There are several slightly different types of Discrete Sine Transforms (DST). One form I saw in W. Press's numerical recipe book is given by

|

(55) |

where  are assumed. This form can be obtained by

replacing DFT's exponential function

are assumed. This form can be obtained by

replacing DFT's exponential function  by

by  . The inverse sine transformation

is given by (I did not derive this, but had numerically verified that

this transform recovers the original data if applied after the sine

transform (55) (code at

/home/yj/project_new/test_space/sine_expansion/t2.f90))

. The inverse sine transformation

is given by (I did not derive this, but had numerically verified that

this transform recovers the original data if applied after the sine

transform (55) (code at

/home/yj/project_new/test_space/sine_expansion/t2.f90))

|

(56) |

which is identical with the forward sine transformation except for the

normalization factor  . (The

terms of index 0 in both Eq. () and () can be dropped since they are

zero. They are kept to make the representation look more similar to the

DFT, where the index begin from zero.) Replacing

. (The

terms of index 0 in both Eq. () and () can be dropped since they are

zero. They are kept to make the representation look more similar to the

DFT, where the index begin from zero.) Replacing  in Eq. (56) by

in Eq. (56) by  , we obtain the

reconstructing function

, we obtain the

reconstructing function

|

(57) |

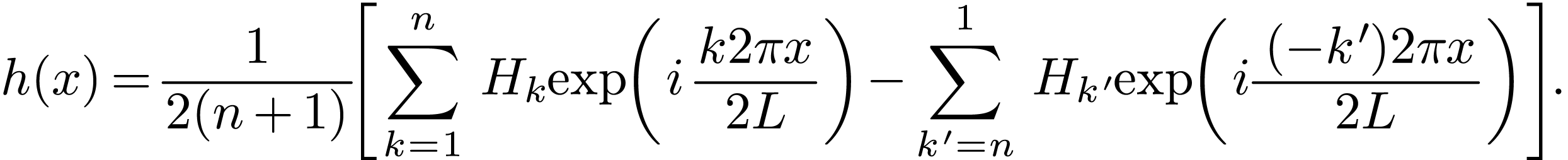

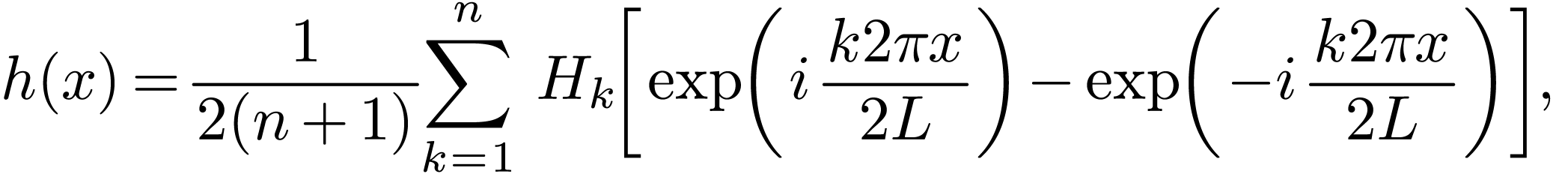

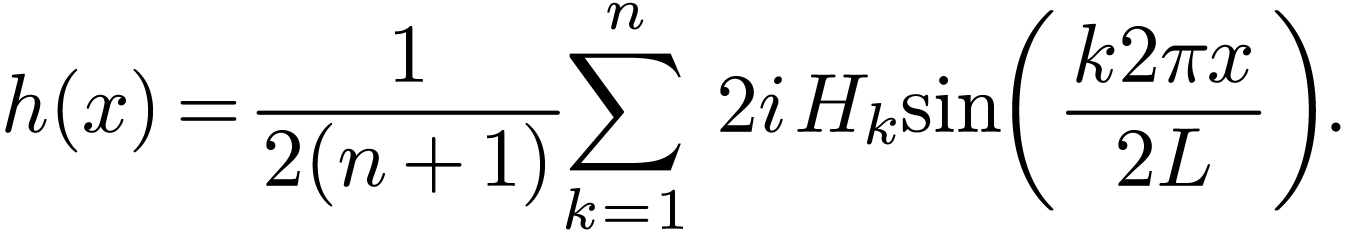

We need a fast method for computing the above DST. All fast methods finally need to make use of the fast method used in the computation of DFT, i.e., FFT. To make use of FFT, we need to define the DST in a way that the DST can be easily connected to the DFT so that FFT can be easily applied. A standard way of making this easy is to define the DST via the DFT of an odd extension of the original data. Next, let us discuss this.

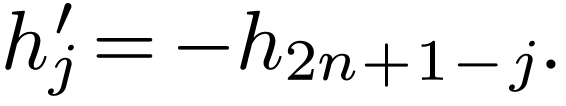

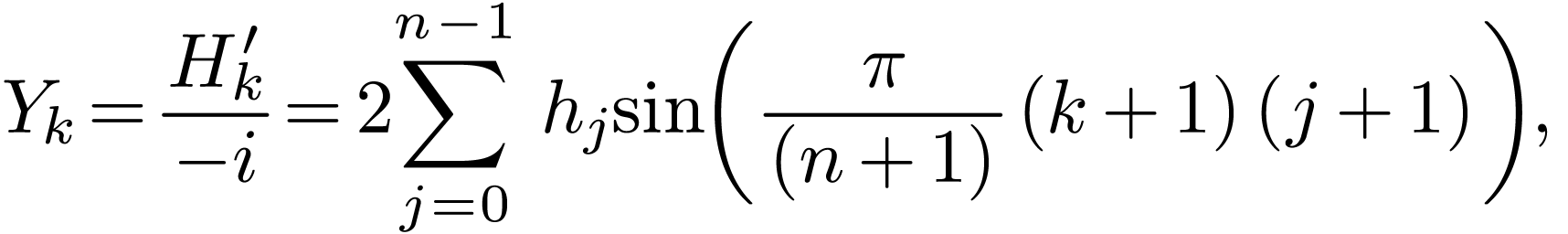

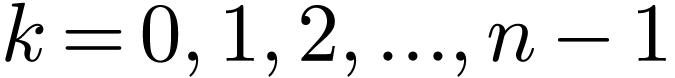

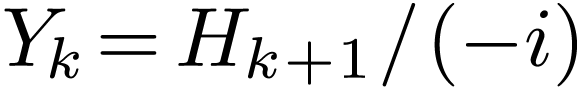

Let us introduce the Discrete Sine Transform (DST) by odd extending a

given real number sequence and then using the DFT of the extended data

to define DST. There are several slightly different ways of odd

extending a given sequence and thus different types of DST. Given a  real number sequence

real number sequence  ,

one frequently adopted odd extension is

,

one frequently adopted odd extension is  .

This odd extension is illustrated in Fig. 5.

.

This odd extension is illustrated in Fig. 5.

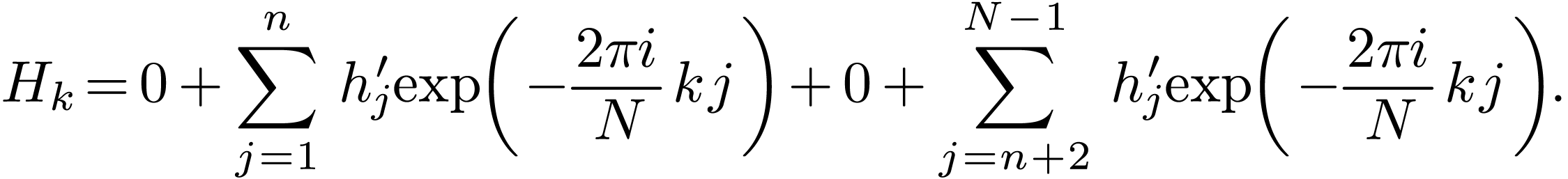

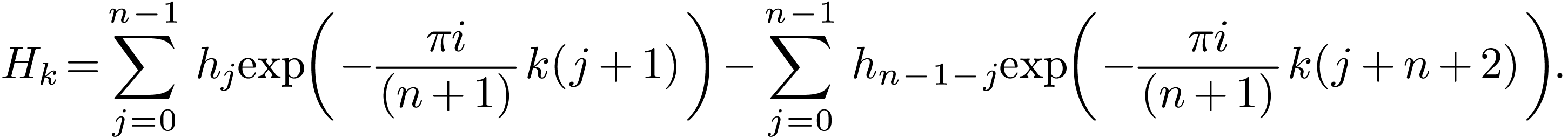

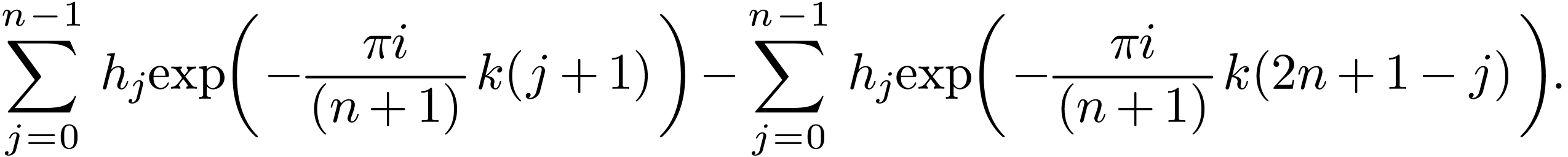

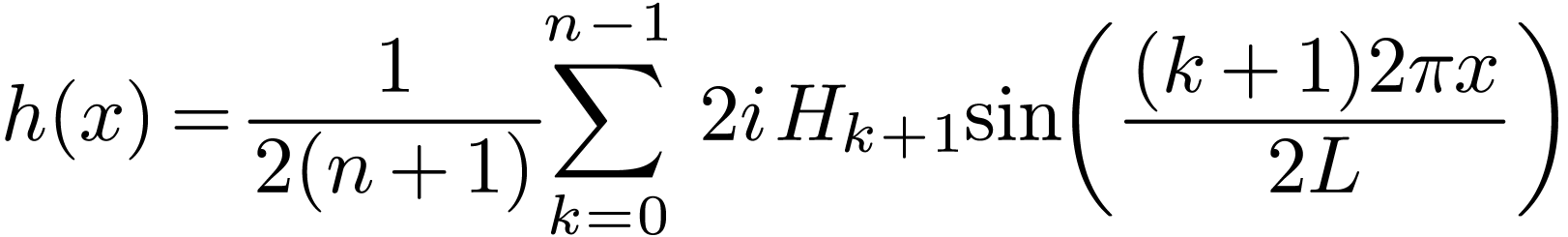

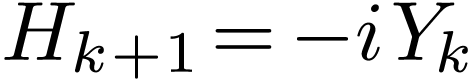

As illustrated in Fig. 5, after the old extension, the

total number of points is  with

with  . Then DFT use the

. Then DFT use the  points with index

points with index  as input. Since the input are

real and odd symmetric sequence, the output of this DFT is an odd

sequence of purely imaginary numbers. Next, let us prove this. The DFT

in this case is given by

as input. Since the input are

real and odd symmetric sequence, the output of this DFT is an odd

sequence of purely imaginary numbers. Next, let us prove this. The DFT

in this case is given by

|

(58) |

where  is the odd extension of the original data

is the odd extension of the original data

. For

. For  , the relation between

, the relation between  and

and

is given by

is given by

|

(59) |

For  , the relation is given

by

, the relation is given

by

|

(60) |

Noting that  and

and  ,

then expression (58) is written as

,

then expression (58) is written as

|

(61) |

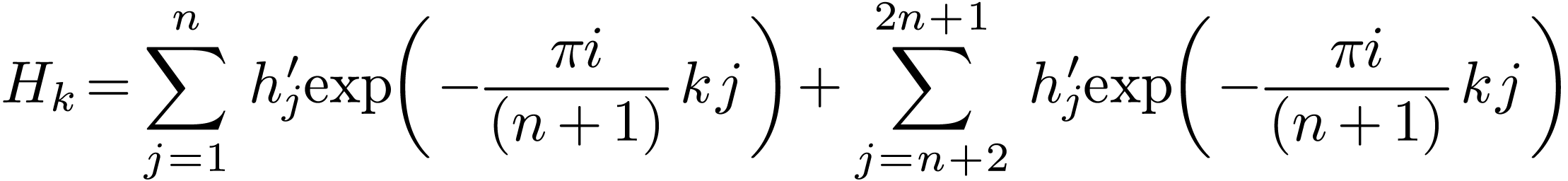

Using  , the above expression

is written as

, the above expression

is written as

|

(62) |

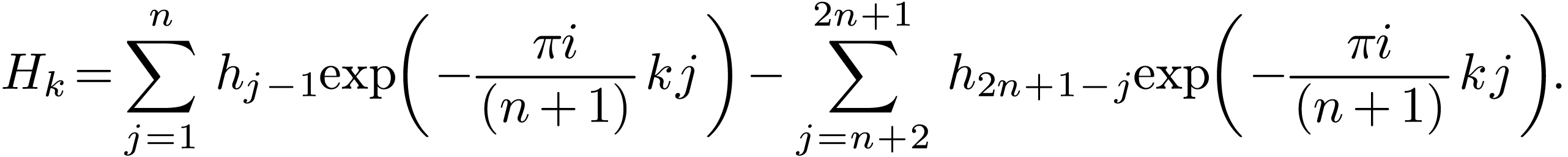

Using the relations (59) and (60) to replace

by

by  ,

the above expression is written

,

the above expression is written

|

(63) |

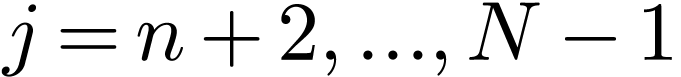

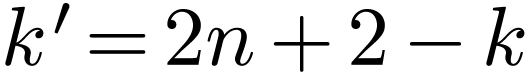

Change the definition of the dummy index  in the

above summation to make it in the conventional range

in the

above summation to make it in the conventional range  , the above expression is written as

, the above expression is written as

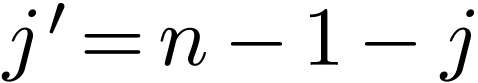

Defining  to replace the dummy index in the

second summation, the above expression is written as

to replace the dummy index in the

second summation, the above expression is written as

which is a purely imaginary number. Expression (64) also

indicates  has the following symmetry

has the following symmetry

|

(65) |

i.e. odd symmetry. Therefore only half of the data for  with

with  need to be stored, namely

need to be stored, namely  with

with  . Expression (64)

indicates that

. Expression (64)

indicates that  and

and  are

definitely zero and thus do not need to be stored. Then the remaining

data to be stored are

are

definitely zero and thus do not need to be stored. Then the remaining

data to be stored are  with

with  , i.e.

, i.e.  .

Following the convention of making the index of

.

Following the convention of making the index of  in the range

in the range  , we define

, we define

. Then

. Then

|

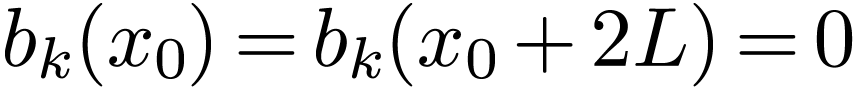

(66) |

with  , which is the index

that we prefer. Finally, the so-called type-I Discrete Sine Transform

(DST-I) is defined based on Eq. (66) via

, which is the index

that we prefer. Finally, the so-called type-I Discrete Sine Transform

(DST-I) is defined based on Eq. (66) via

|

(67) |

with  . This is the RODFT00

transform defined in the FFTW library.

. This is the RODFT00

transform defined in the FFTW library.

From the above derivation, we know that the DST,  , is related to the DFT,

, is related to the DFT,  , by

, by  ,

and thus the meaning of

,

and thus the meaning of  is in principle clear.

Next, let us use the DST to reconstruct the original function from which

the data are sampled. Since DST is only a special case of DFT,

reconstructing the function using DST follows the same procedure used in

DFT. In DFT, the function is reconstructed via Eq. (42)

(changing to the positive exponent convention), i.e.,

is in principle clear.

Next, let us use the DST to reconstruct the original function from which

the data are sampled. Since DST is only a special case of DFT,

reconstructing the function using DST follows the same procedure used in

DFT. In DFT, the function is reconstructed via Eq. (42)

(changing to the positive exponent convention), i.e.,

|

(68) |

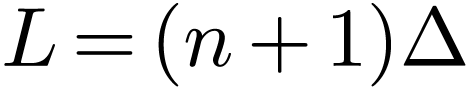

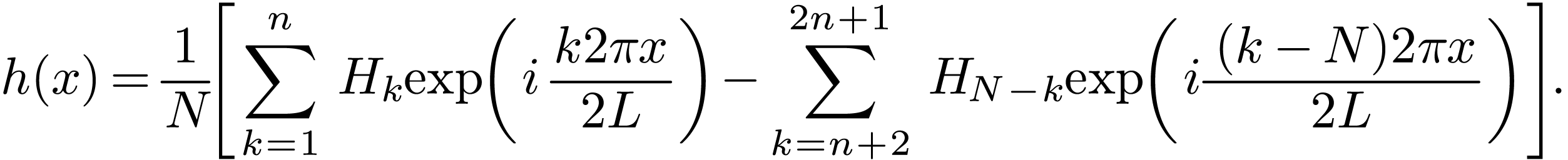

where  is the length of the interval in which the

samplings

is the length of the interval in which the

samplings  with

with  are made.

For our present case, i.e., an odd extension of the original

are made.

For our present case, i.e., an odd extension of the original  data, we have

data, we have  and

and  and

and  . Then Eq. (68)

is written as

. Then Eq. (68)

is written as

|

(69) |

Using the odd symmetry of  ,

i.e.,

,

i.e.,  , the above expansion

is written as

, the above expansion

is written as

|

(70) |

Define  , and note that

, and note that  , then the above expression is

written as

, then the above expression is

written as

|

(71) |

i.e.,

|

(72) |

which is simplified as

|

(73) |

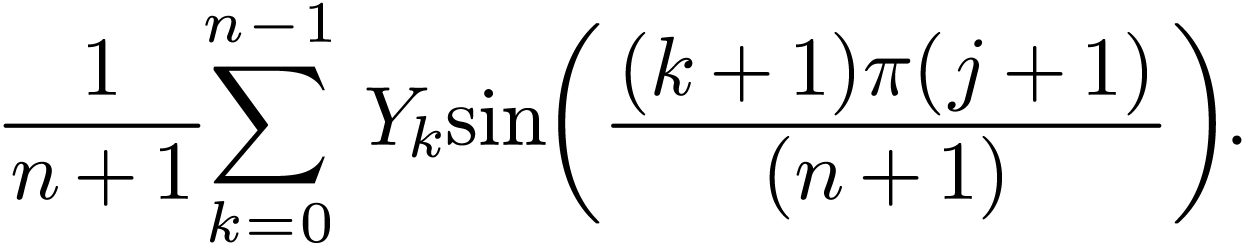

As a convention, we prefer that the summation index begins from 0 and

ends at  . Then expression (73) is written as

. Then expression (73) is written as

Using the relation between DST and DFT, i.e.,  , the above equation is written as

, the above equation is written as

|

(74) |

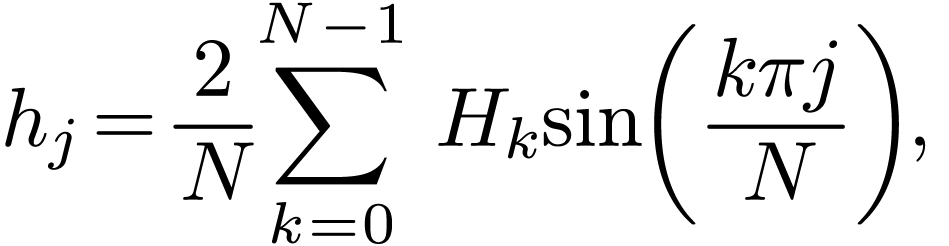

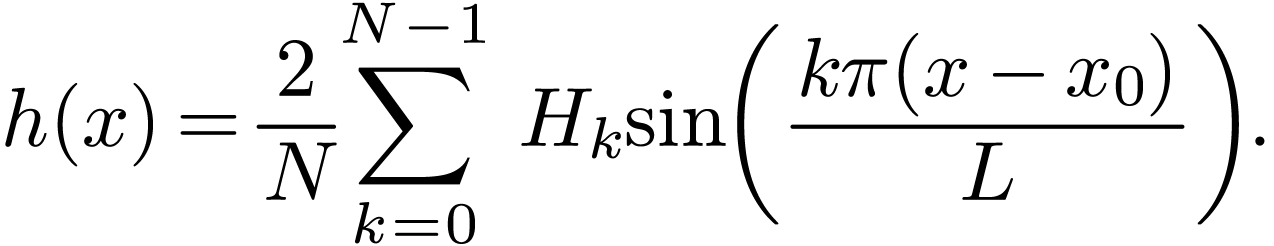

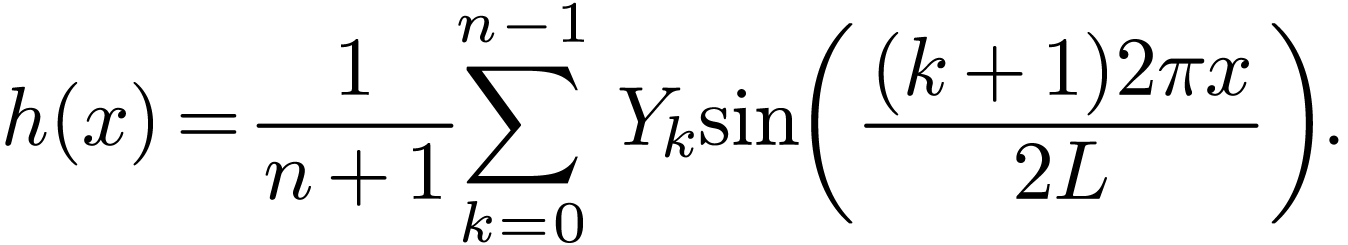

This is the formula for constructing the continuous function using the

DST data. This formula is an expansion over the basis functions  with the DST

with the DST  acting as the

expansion coefficients. Therefore the direct meaning of the DST,

acting as the

expansion coefficients. Therefore the direct meaning of the DST,  , is that they are the expansion

coefficients when using

, is that they are the expansion

coefficients when using  as the basis functions

to approximate a function in the domain

as the basis functions

to approximate a function in the domain  .

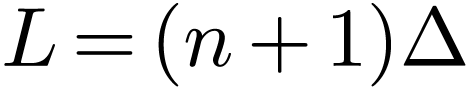

From Fig. 5, we know that the interval length

.

From Fig. 5, we know that the interval length  is given by

is given by  ,

where

,

where  is the uniform spacing between the

original

is the uniform spacing between the

original  sampling points.

sampling points.

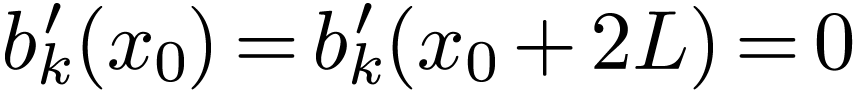

Evaluate the function in Eq. (74) at  with

with  , then we obtain

, then we obtain

It can be proved that  in the above equation

exactly recover

in the above equation

exactly recover  used in defining the DST

used in defining the DST  . Therefore Eq. (75)

is the Inverse Discrete Sine Transform.

. Therefore Eq. (75)

is the Inverse Discrete Sine Transform.

to be written

The trigonometric identity

|

(76) |

indicates that nonlinear interaction between two waves of the same frequency generates zero frequency component and its second harmonic. The process of generating of second-harmonic is also called frequency doubling.

Signals that are not band-limited usually contains all frequencies and

thus do not satisfy the condition required by the sampling theorem

(i.e.,  for

for  ).

In this case, for any given

).

In this case, for any given  data, we can still

calculate its DFT by using Eq. (34). However the results

obtained are meaningful only when

data, we can still

calculate its DFT by using Eq. (34). However the results

obtained are meaningful only when  approaches

zero as the frequency approaches

approaches

zero as the frequency approaches  from above and

approaches

from above and

approaches  from below, i.e., only when the

results obtained are consistent with the assumption used to obtain the

results (the assumption is that

from below, i.e., only when the

results obtained are consistent with the assumption used to obtain the

results (the assumption is that  for

for  ). When the results obtained do not satisfy the

above condition, then it indicates that the “aliasing

errors” have contributed to the results. We can reduce the

aliasing errors by increasing the sampling frequency. The aliasing

errors can be reduced but can not be completely removed for a

non-band-limited signal.

). When the results obtained do not satisfy the

above condition, then it indicates that the “aliasing

errors” have contributed to the results. We can reduce the

aliasing errors by increasing the sampling frequency. The aliasing

errors can be reduced but can not be completely removed for a

non-band-limited signal.

In signal processing and related disciplines, aliasing is an effect that causes different signals to become indistinguishable (or aliases of one another) when sampled. It also often refers to the distortion or artifact that results when a signal reconstructed from samples is different from the original continuous signal.

An alias is a false lower frequency component that appears in sampled data acquired at too low a sampling rate.

Aliasing errors are hard to detect and almost impossible to remove using software. The solution is to use a high enough sampling rate, or if this is not possible, to use an anti-aliasing filter in front of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) to eliminate the high frequency components before they get into the data acquisition system.

When a digital image is viewed, a reconstruction is performed by a display or printer device, and by the eyes and the brain. If the image data is processed in some way during sampling or reconstruction, the reconstructed image will differ from the original image, and an alias is seen.

Aliasing can be caused either by the sampling stage or the reconstruction stage; these may be distinguished by calling sampling aliasing (prealiasing) and reconstruction aliasing (postaliasing).

In video or cinematography, temporal aliasing results from the limited frame rate, and causes the wagon-wheel effect, whereby a spoked wheel appears to rotate too slowly or even backwards. Aliasing has changed its apparent frequency of rotation. A reversal of direction can be described as a negative frequency. Temporal aliasing frequencies in video and cinematography are determined by the frame rate of the camera, but the relative intensity of the aliased frequencies is determined by the shutter timing (exposure time) or the use of a temporal aliasing reduction filter during filming.

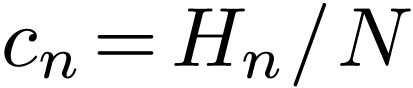

In the above, we go through the process “Fourier series Fourier transformation

Fourier transformation  DFT”, which corresponds to going from the

discrete case (Fourier series) to the continuous case (Fourier

transformation), and then back to the discrete case (DFT). Since both

Fourier series and DFT are discrete in frequency, it is instructive to

examine the relation between the Fourier coefficient

DFT”, which corresponds to going from the

discrete case (Fourier series) to the continuous case (Fourier

transformation), and then back to the discrete case (DFT). Since both

Fourier series and DFT are discrete in frequency, it is instructive to

examine the relation between the Fourier coefficient  and the DFT

and the DFT  . The Fourier

coefficient of

. The Fourier

coefficient of  is given by Eq. (93),

i.e.,

is given by Eq. (93),

i.e.,

|

(77) |

which can be equivalently written

|

(78) |

where  . On the other hand, if

. On the other hand, if

is sampled with sampling rate

is sampled with sampling rate  , then the number of sampling points per period

is

, then the number of sampling points per period

is  . Then the frequency at

which the Fourier transform

. Then the frequency at

which the Fourier transform  is evaluated in

getting the DFT [Eq. (36)] is written

is evaluated in

getting the DFT [Eq. (36)] is written

|

(79) |

which is identical to the frequency to which the Fourier coefficient

corresponds. Using

corresponds. Using  in

Eq. (78), we obtain

in

Eq. (78), we obtain

i.e., dividing the DFT  by

by  gives the corresponding Fourier expansion coefficient

gives the corresponding Fourier expansion coefficient  . We can further use Eqs. (29) and

(30) to recover the Fourier coefficients in terms of

trigonometric functions cosine and sine,

. We can further use Eqs. (29) and

(30) to recover the Fourier coefficients in terms of

trigonometric functions cosine and sine,

Note that the approximation in Eq. (80) becomes an exact

relation if the largest frequency contained in  is less than

is less than  .

.

The Fast Fourier Transform algorithm (FFT) makes the DFT fast enough to solve many real-life problems, which makes FFT be among the top algorithms that have changed the world. The FFT algorithm remained mysterious to me for many years until I read Cooley and Tukey's original paper (An algorithm for the machine calculation of complex Fourier series), which turns out to be a very concise paper and easy to follow.

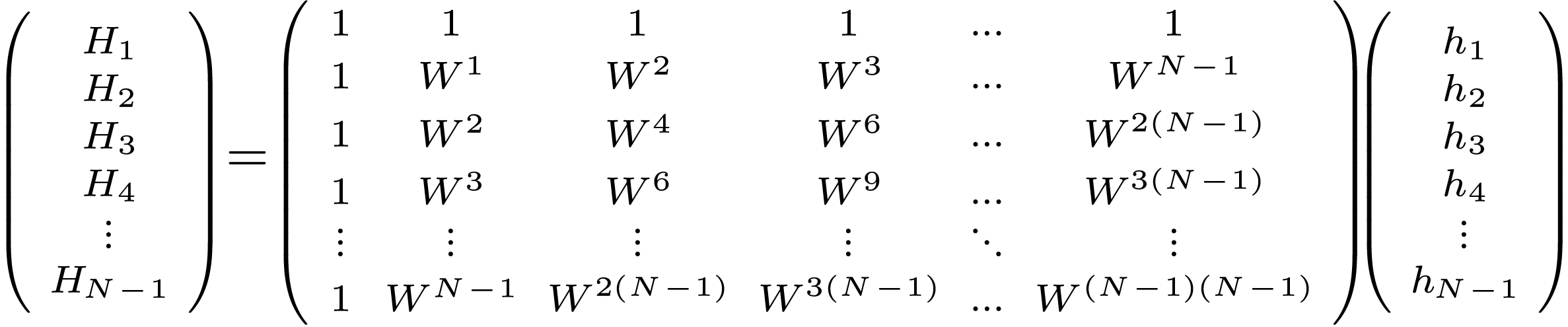

The DFT is defined by Eq. (34), i.e.,

|

(82) |

where  . Equations (82)

indicates that the DFT is the multiplication of a transformation matrix

. Equations (82)

indicates that the DFT is the multiplication of a transformation matrix

with a column vector

with a column vector  , where the transformation matrix

, where the transformation matrix  is symmetric and called DFT matrix. In the matrix form, the DFT is

written as

is symmetric and called DFT matrix. In the matrix form, the DFT is

written as

|

(83) |

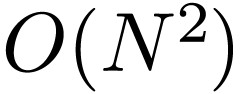

If directly using the definition in Eq. (83) to compute

DFT, then a matrix multiplication need to be performed, which requires

operations. Here the powers of

operations. Here the powers of  are assumed to be pre-computed, and we define “an operation”

as a multiplication followed by an addition.

are assumed to be pre-computed, and we define “an operation”

as a multiplication followed by an addition.

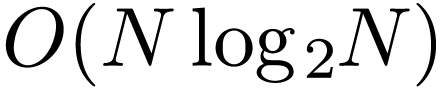

The Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT) algorithm manage to reduce the

complexity of computing the DFT from  to

to  by factoring the DFT matrix

by factoring the DFT matrix  into a product of sparse matrices.

into a product of sparse matrices.

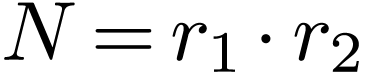

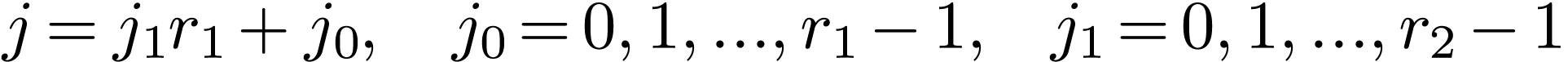

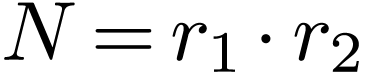

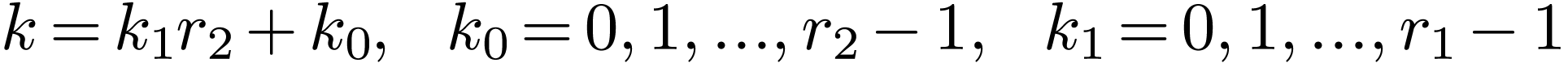

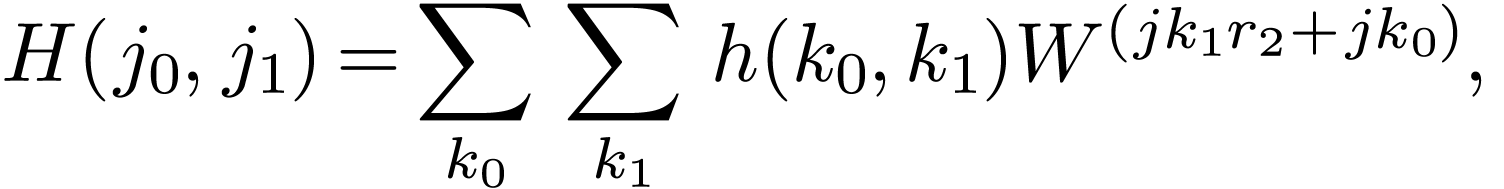

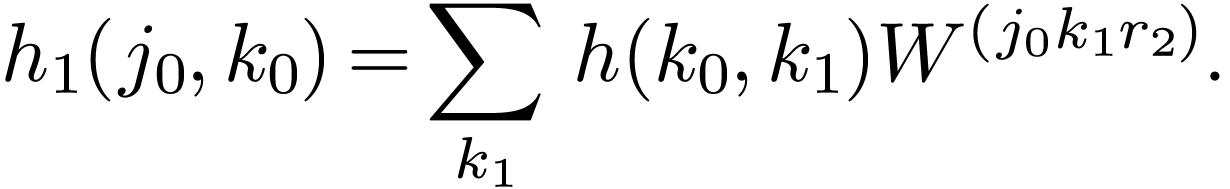

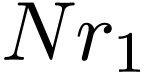

Suppose  is a composite, i.e.,

is a composite, i.e.,  . Then the indices in Eq. (82) can

be expressed as

. Then the indices in Eq. (82) can

be expressed as

|

(84) |

|

(85) |

Then, one can write

|

(86) |

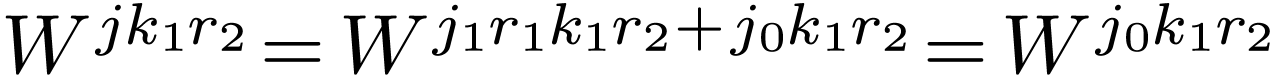

Noting that

|

(87) |

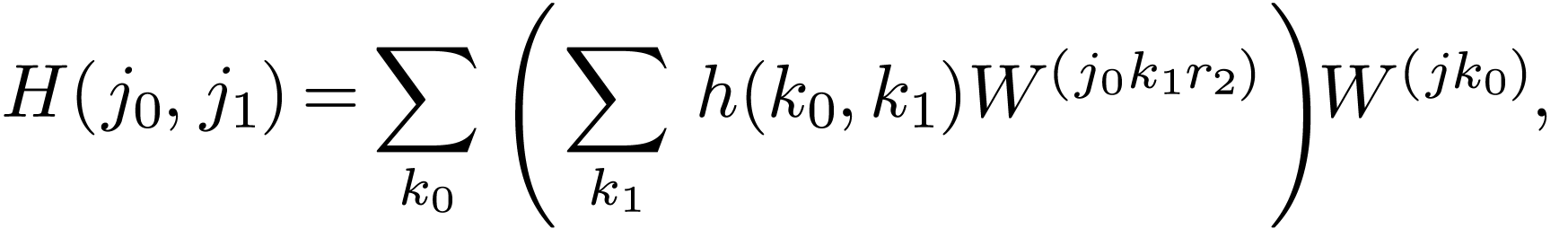

Eq. () is written as

|

(88) |

where the inner sum over  is independent of

is independent of  and can be defined as a new array

and can be defined as a new array

|

(89) |

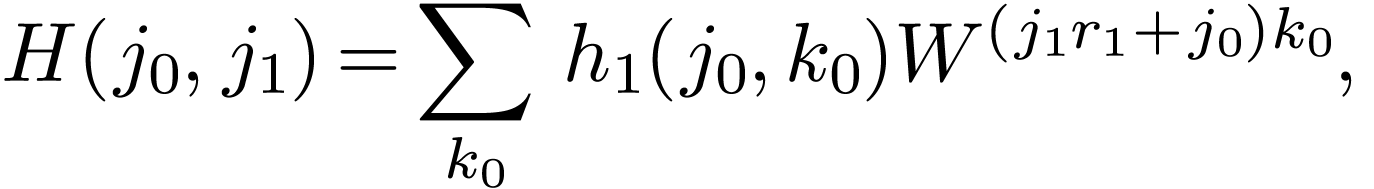

Then

|

(90) |

There are  elements in the array

elements in the array  , each requiring

, each requiring  operations, giving a total of

operations, giving a total of  operation to

obtain

operation to

obtain  . Similarly, it takes

. Similarly, it takes

operations to calculate

operations to calculate  from

from  . Therefore, this

two-step algorithm requires a total of

. Therefore, this

two-step algorithm requires a total of  operations.

operations.

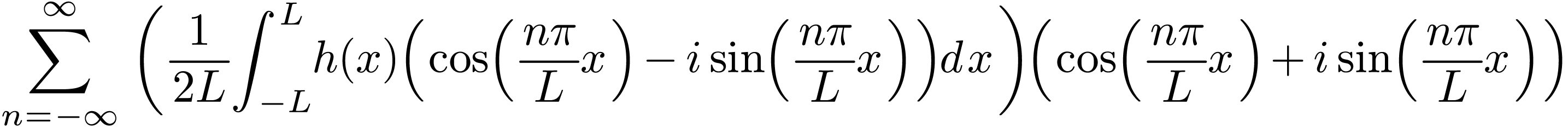

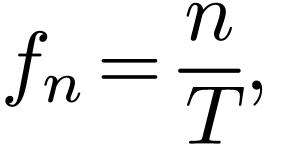

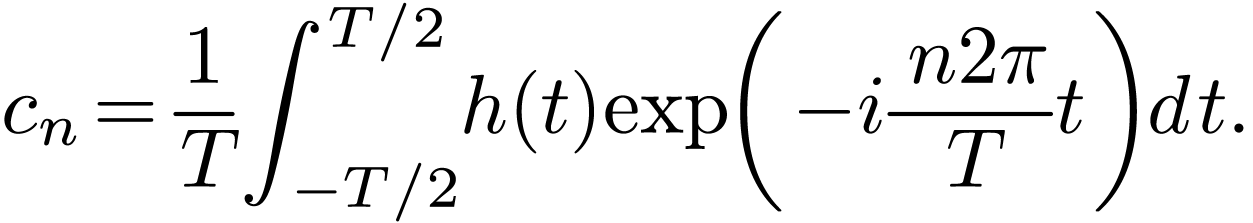

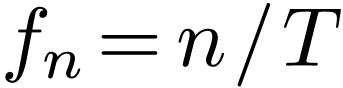

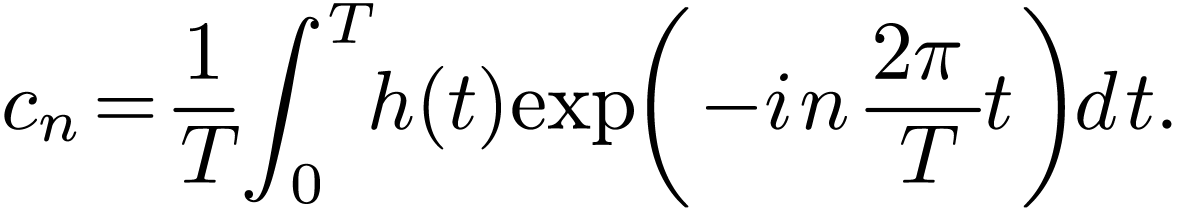

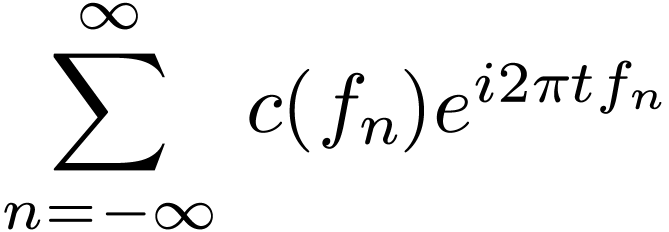

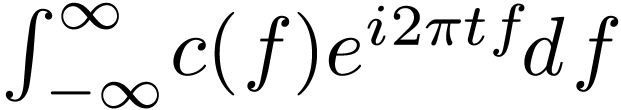

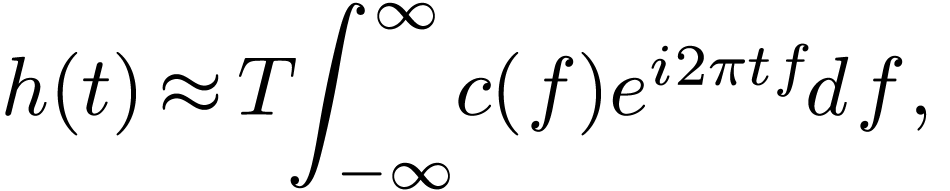

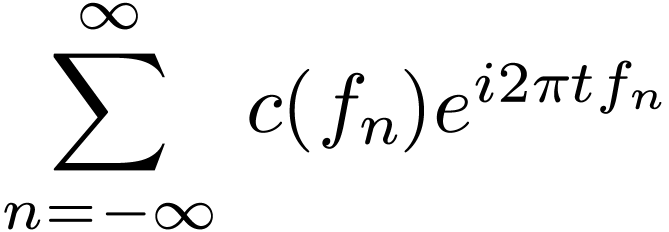

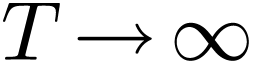

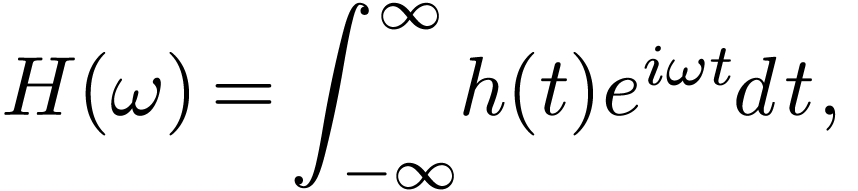

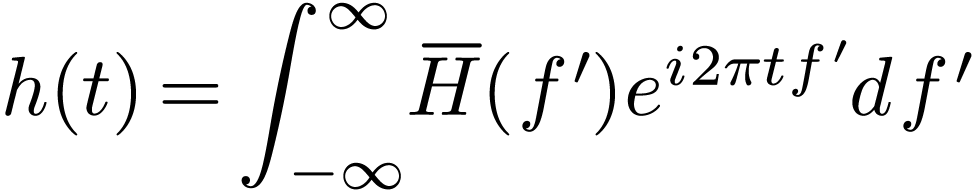

Fourier transformation

Fourier transformationThe Fourier series discussed above indicates that a periodic function is composed of discrete spectrum and is written as

|

(91) |

where  is the period of

is the period of  . The

. The  th

term of the above Fourier series corresponds to a harmonic of frequency

th

term of the above Fourier series corresponds to a harmonic of frequency

|

(92) |

and the expansion coefficient  is given by

is given by

|

(93) |

In terms of  , the coefficient

in Eq. (93) is written

, the coefficient

in Eq. (93) is written

|

(94) |

In terms of  , the Fourier

series in Eq. (91) is written

, the Fourier

series in Eq. (91) is written

Note that  is the value of function

is the value of function  at

at  . Further

note that the interval between

. Further

note that the interval between  and

and  is

is  . Thus the

above summation is the rectangular formula for numerically calculating

the integration

. Thus the

above summation is the rectangular formula for numerically calculating

the integration  . Therefore,

equation (95) can be approximately written as

. Therefore,

equation (95) can be approximately written as

|

(96) |

which will become exact when the interval  ,

i.e.,

,

i.e.,  . Therefore, for the

case

. Therefore, for the

case  , the Fourier series

exactly becomes

, the Fourier series

exactly becomes

|

(97) |

where  is given by Eq. (94), i.e.,

is given by Eq. (94), i.e.,

|

(98) |

Note that the function  given in Eq. (97)

is proportional to

given in Eq. (97)

is proportional to  while the function

while the function  given in Eq. (98) is proportional to

given in Eq. (98) is proportional to  . Since

. Since  , it is desired to eliminate the

, it is desired to eliminate the  and

and  factors in Eqs. (97) and (98), which can be easily achieved by defining a new function

factors in Eqs. (97) and (98), which can be easily achieved by defining a new function

|

(99) |

Then equations (97) and (98) are written as

|

(100) |

|

(101) |

Equations (100) and (101) are the Fourier transformation pairs discussed in the next section.

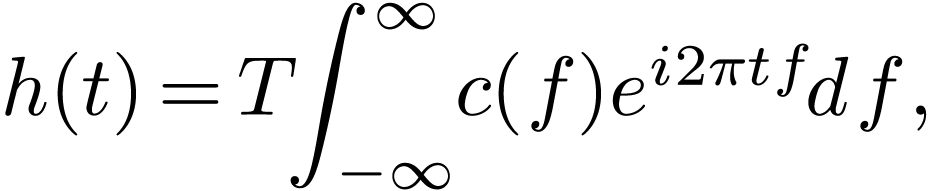

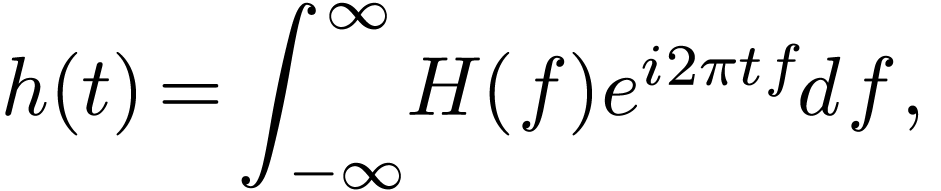

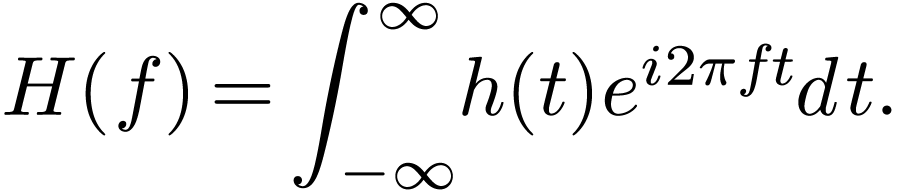

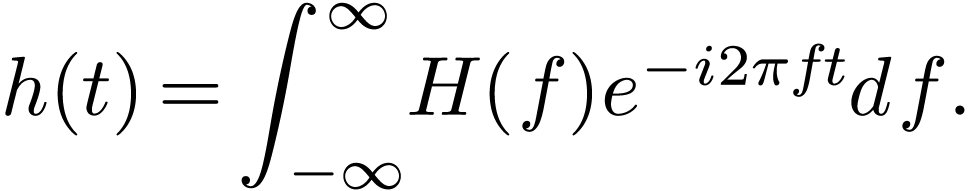

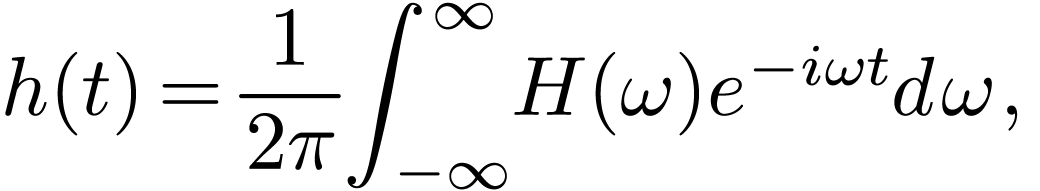

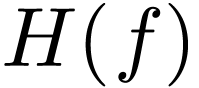

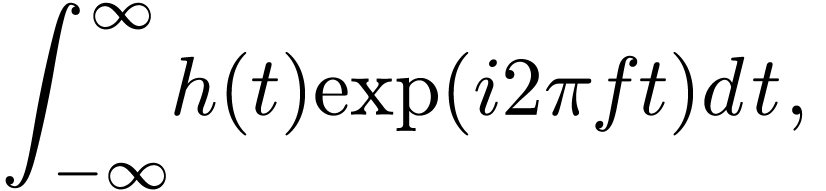

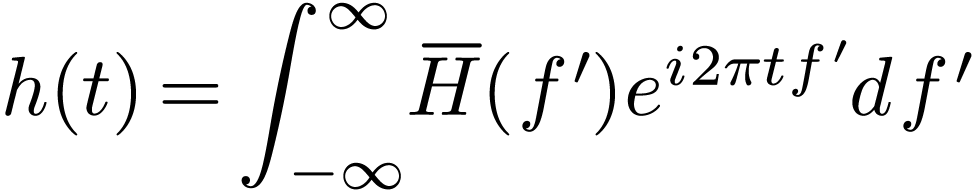

As discussed above, the Fourier transformation of a function  is given by

is given by

|

(102) |

Once the Fourier transformation  is known, the

original function

is known, the

original function  can be reconstructed via

can be reconstructed via

|

(103) |

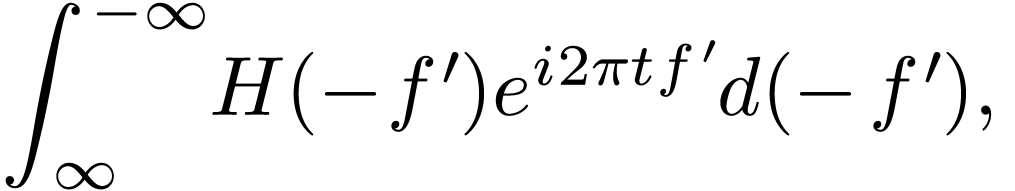

[Note that the signs in the exponential of Eq. (100) and

(101) are opposite. Which one should be minus or positive

is actually a matter of convention because a trivial variable

substitution  can change the sign between minus

and positive. Proof. In terms of

can change the sign between minus

and positive. Proof. In terms of  ,

Eq. (103) is written

,

Eq. (103) is written

Define

Then Eq. (104) is written

|

(106) |

The signs in the exponential of Eqs. (105) and (106) are opposite to Eqs. (102) and (103), respectively.]

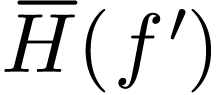

[Some physicists prefer to use the angular frequency  rather than the frequency

rather than the frequency  to represent the

Fourier transformation. Using

to represent the

Fourier transformation. Using  ,

equations. (102) and (103) are written,

respectively, as

,

equations. (102) and (103) are written,

respectively, as

|

(107) |

|

(108) |

where we see that the asymmetry between the Fourier transformation and

its inverse is more severe in this representation: besides the

opposite-sign in the exponents, there is also a  factor difference between the Fourier transformation and its inverse.

Whether the

factor difference between the Fourier transformation and its inverse.

Whether the  factor appears at the forward

transformation or inverse one is actually a matter of convention. The

only requirement is that the product of the two factors in the forward

and inverse transformation is equal to

factor appears at the forward

transformation or inverse one is actually a matter of convention. The

only requirement is that the product of the two factors in the forward

and inverse transformation is equal to  .

To obtain a more symmetric pair, one can adopt a factor

.

To obtain a more symmetric pair, one can adopt a factor  at both the forward and inverse transformation. The representation in

Eqs. (102) and (103) is adopted in this note.

But we should know how to change to the

at both the forward and inverse transformation. The representation in

Eqs. (102) and (103) is adopted in this note.

But we should know how to change to the  representation when needed.]

representation when needed.]

[

|

(109) |

]

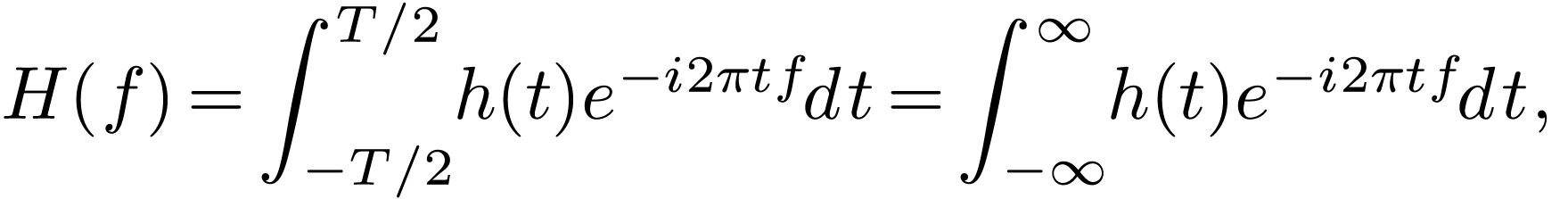

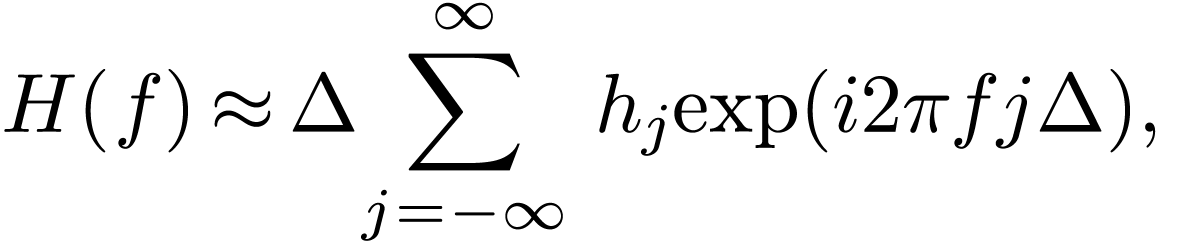

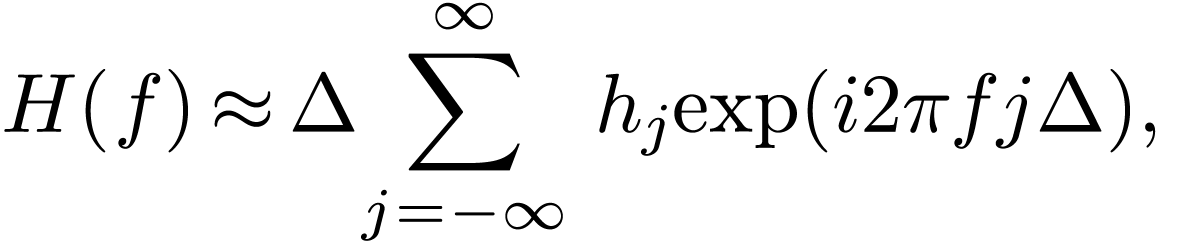

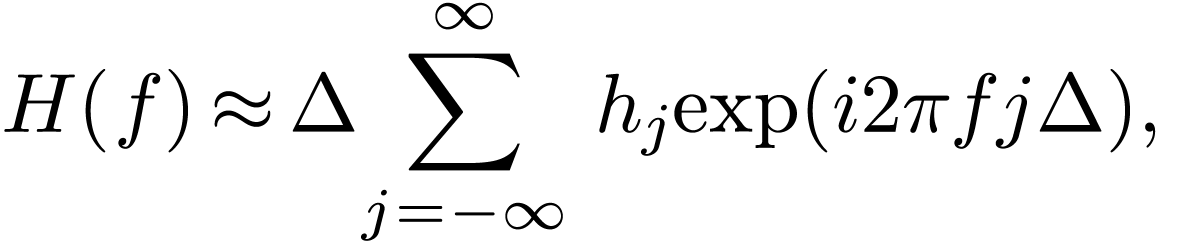

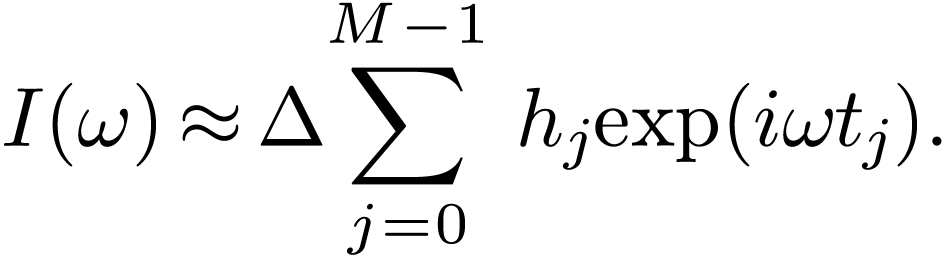

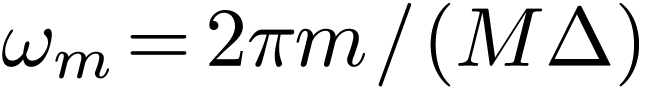

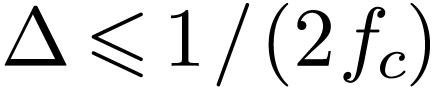

Next, consider how to numerically compute the Fourier transformation of

a function  . A simple way is

to use the rectangle formula to approximate the integration in Eq. (102), i.e.,

. A simple way is

to use the rectangle formula to approximate the integration in Eq. (102), i.e.,

|

(110) |

where  and

and  with

with  . Note Eq. (110) is an

approximation, which will become exact if

. Note Eq. (110) is an

approximation, which will become exact if  .

In practice, we can sample

.

In practice, we can sample  only with a nonzero

only with a nonzero

. Therefore Eq. (110)

is usually an approximation. Do we have some rules to choose a suitable

. Therefore Eq. (110)

is usually an approximation. Do we have some rules to choose a suitable

so that Eq. (110) can become a good

approximation or even an exact relation? This important question is

answered by the sampling theorem, which sates that a suitable

so that Eq. (110) can become a good

approximation or even an exact relation? This important question is

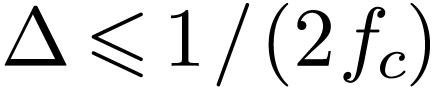

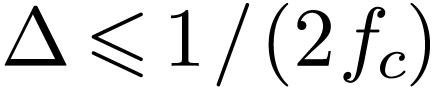

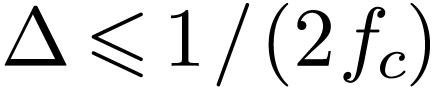

answered by the sampling theorem, which sates that a suitable  to make Eq. (110) exact is given by

to make Eq. (110) exact is given by  , where

, where  is

the largest frequency contained in

is

the largest frequency contained in  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  for

for  ).

).

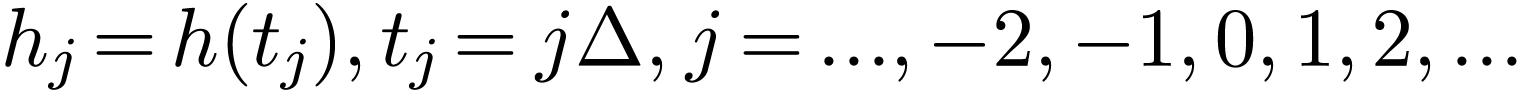

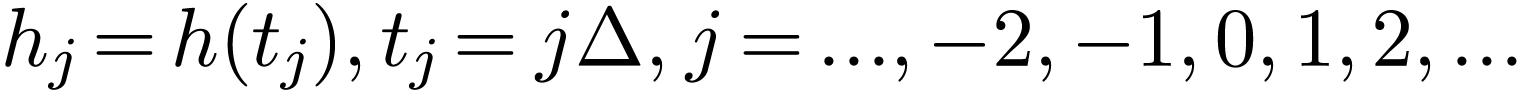

In computational and experimental work, we know only a list of values

sampled at discrete values of

sampled at discrete values of  . Let us suppose that

. Let us suppose that  is sampled with uniform interval between consecutive points:

is sampled with uniform interval between consecutive points:

|

(111) |

The sampling rate is defined by  .

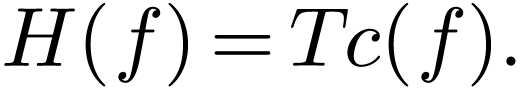

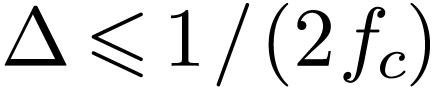

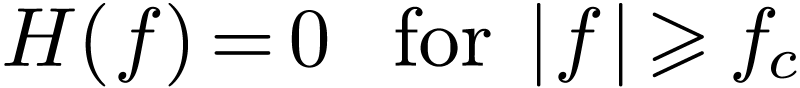

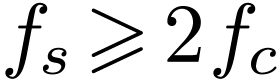

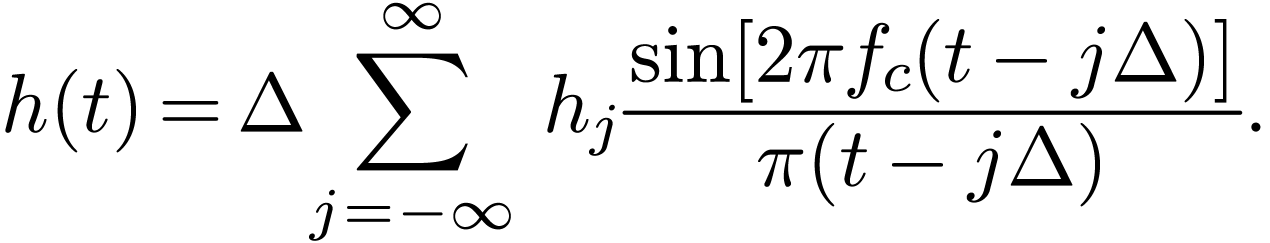

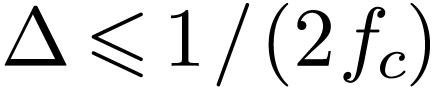

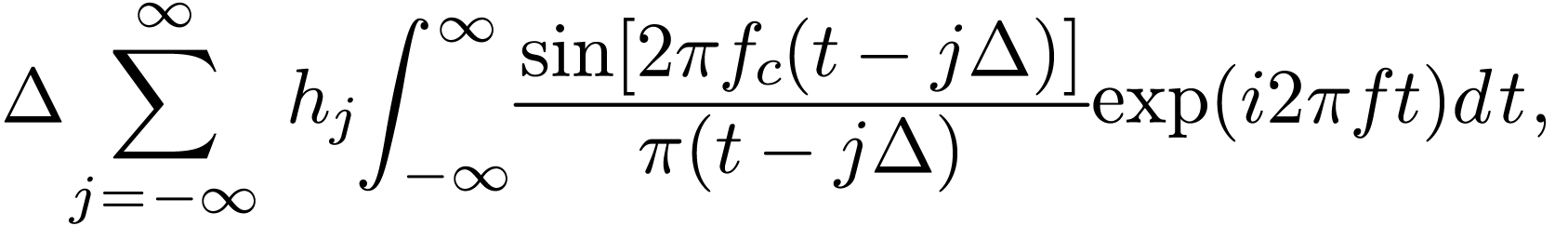

The sampling theorem states that: If the Fourier transformation of

function

.

The sampling theorem states that: If the Fourier transformation of

function  ,

,  , has the following property

, has the following property

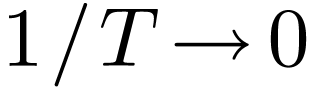

|

(112) |

then sampling  with the sampling rate

with the sampling rate  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  ) will

completely determine

) will

completely determine  , which

is given explicitly by the formula

, which

is given explicitly by the formula

|

(113) |

We will not concern us here with the proof of the sampling theorem and

simply start working with Eq. (113) to derive the concrete

expression for the Fourier transformation of  . Substituting the expression (113) for

. Substituting the expression (113) for

into the Fourier transformation (102),

we obtain the explicit form of the Fourier transformation of

into the Fourier transformation (102),

we obtain the explicit form of the Fourier transformation of  :

:

With the help of Wolfram Mathematica, the integration in Eq. (114) is evaluated analytically, giving

|

(115) |

Using this, Eq. (114) is written

|

(116) |

which shows that  for

for  , which is consistent with the assumption of

sampling theorem, i.e.,

, which is consistent with the assumption of

sampling theorem, i.e.,  has the property given

in Eq. (112). The second line of Eq. (116) is

identical to Eq. (110) except that Eq. (116)

in this case is exact while Eq. (110) is only approximate.

In other words, if

has the property given

in Eq. (112). The second line of Eq. (116) is

identical to Eq. (110) except that Eq. (116)

in this case is exact while Eq. (110) is only approximate.

In other words, if  , then the

Fourier transformation is exactly given by Eq. (116), where

, then the

Fourier transformation is exactly given by Eq. (116), where

is the largest frequency contained in

is the largest frequency contained in  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  for

for  ).

).

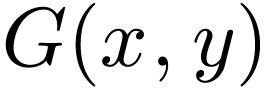

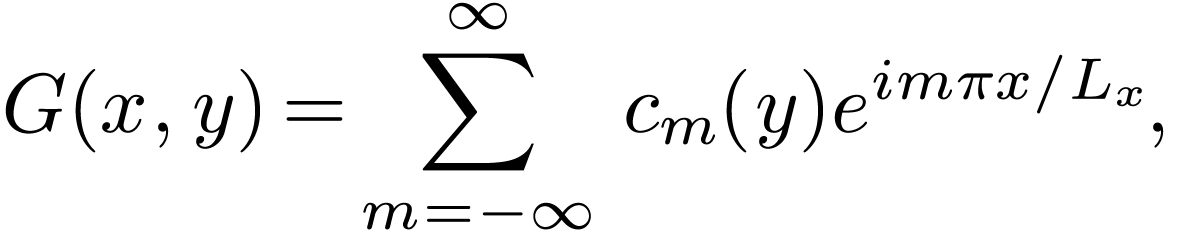

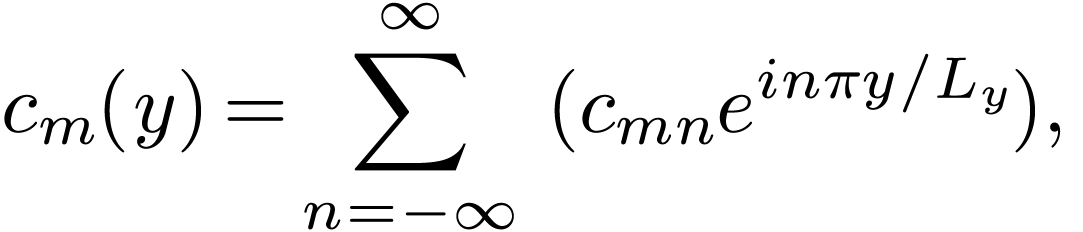

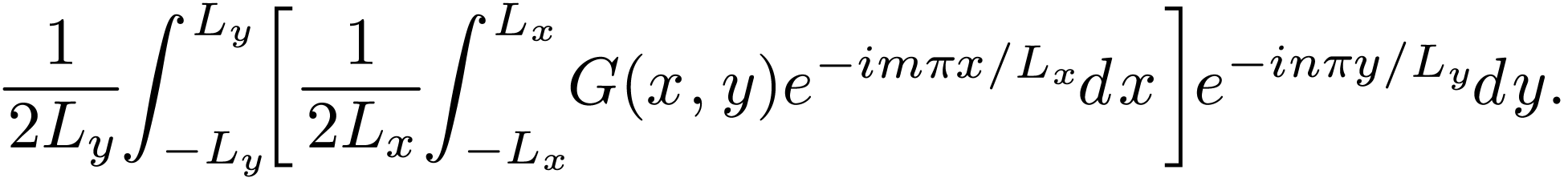

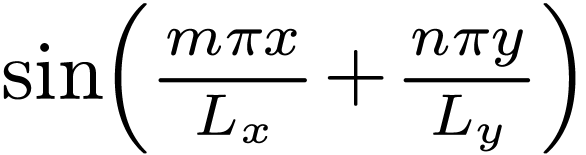

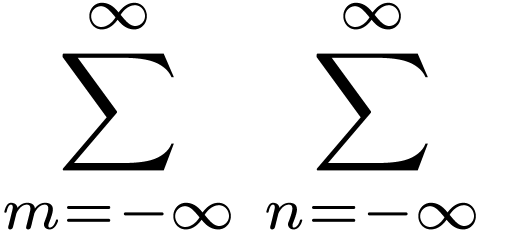

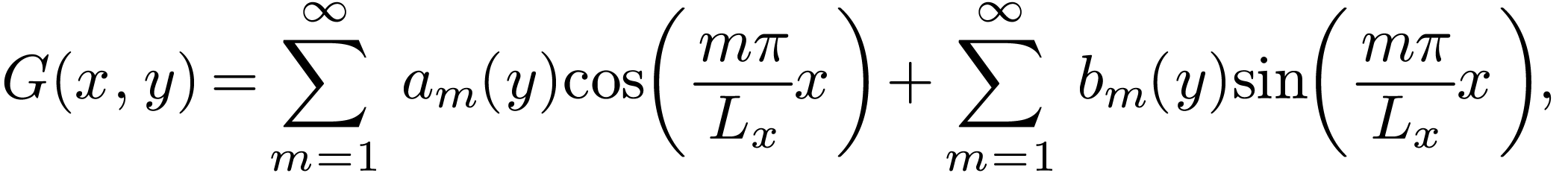

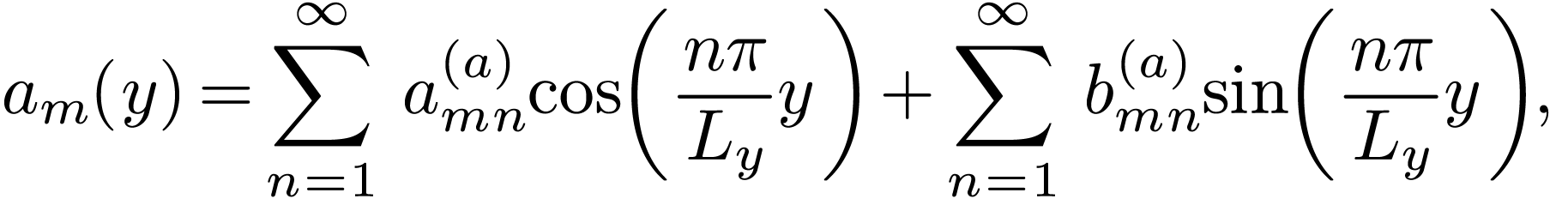

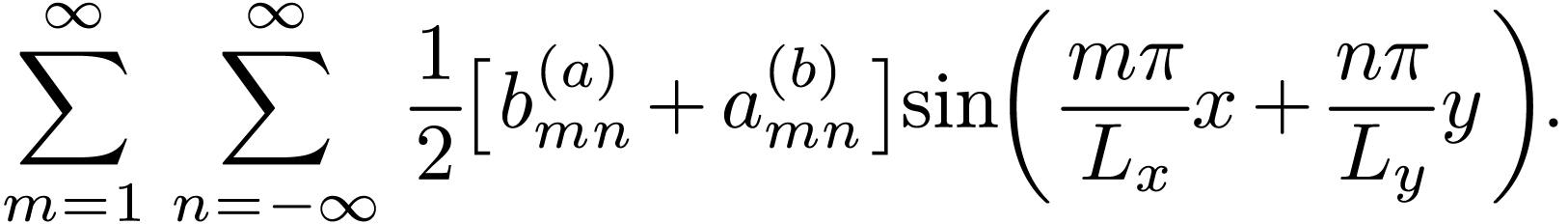

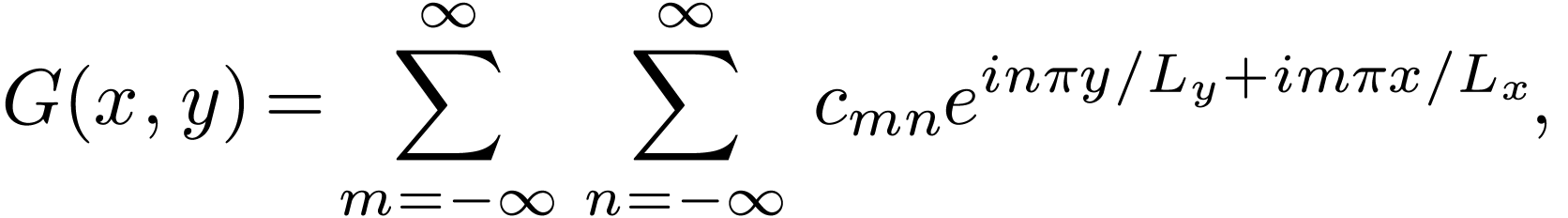

Compared with Eq. (1) that uses the trigonometric

functions, Fourier series (15) and (16), which

is expressed in terms of the complex exponential function  , is more compact. The convenience introduced

by the complex exponential function is more obvious when we deal with

multiple-dimensional cases. For example, a two-dimensional function

, is more compact. The convenience introduced

by the complex exponential function is more obvious when we deal with

multiple-dimensional cases. For example, a two-dimensional function  can be expanded as Fourier series about

can be expanded as Fourier series about  ,

,

|

(117) |

where  is the period of

is the period of  in

in  direction. The expansion coefficients

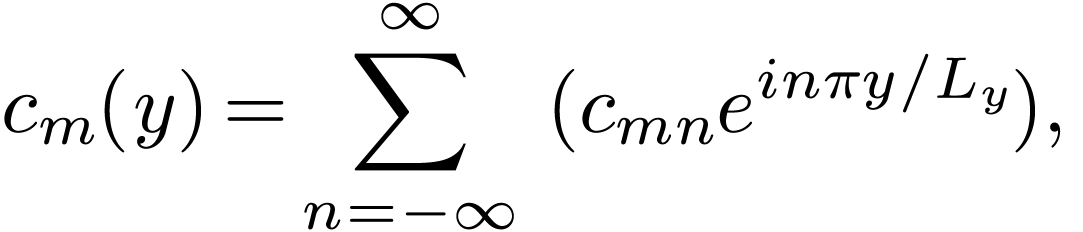

direction. The expansion coefficients  can be further expanded as Fourier series about

can be further expanded as Fourier series about  ,

,

|

(118) |

where  is the period of

is the period of  in

in  direction, and the coefficients

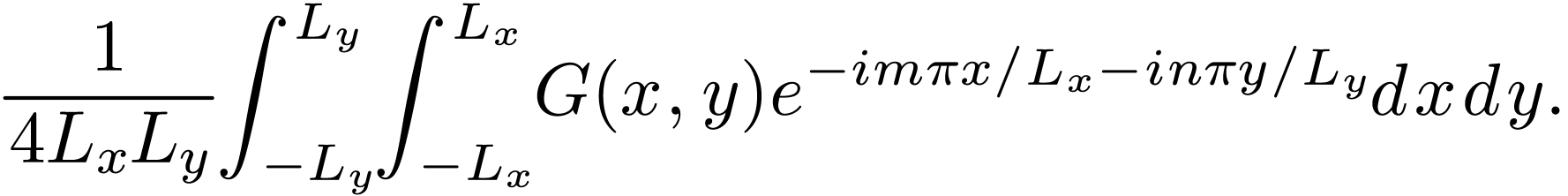

direction, and the coefficients  is given by

is given by

Using Eq. (118) in Eq. (117), we obtain

|

(120) |

Equations (120) and (119) give the

two-dimensional Fourier series of  .

.

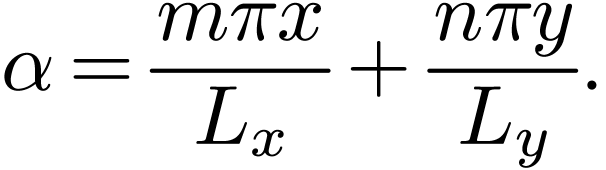

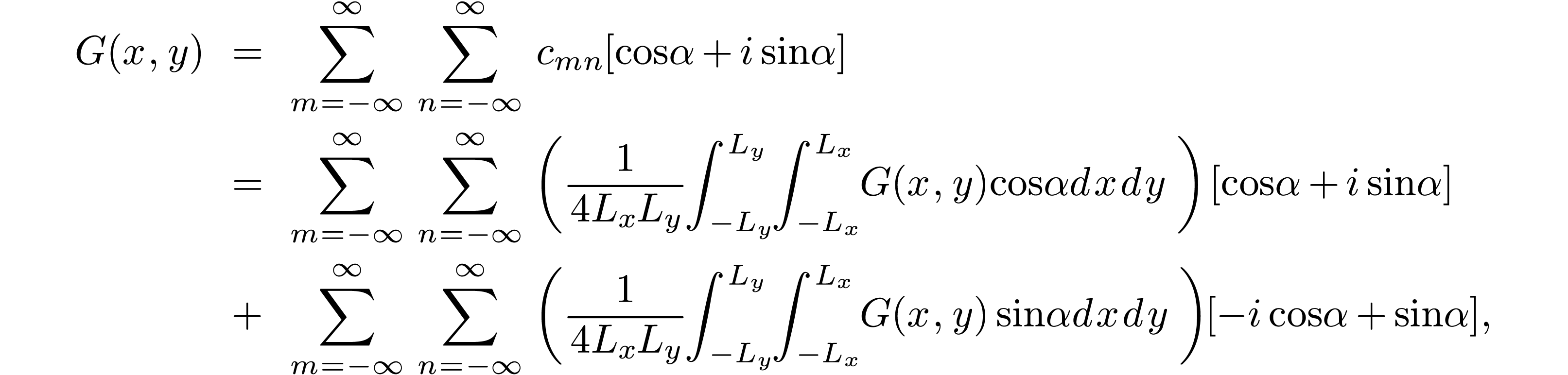

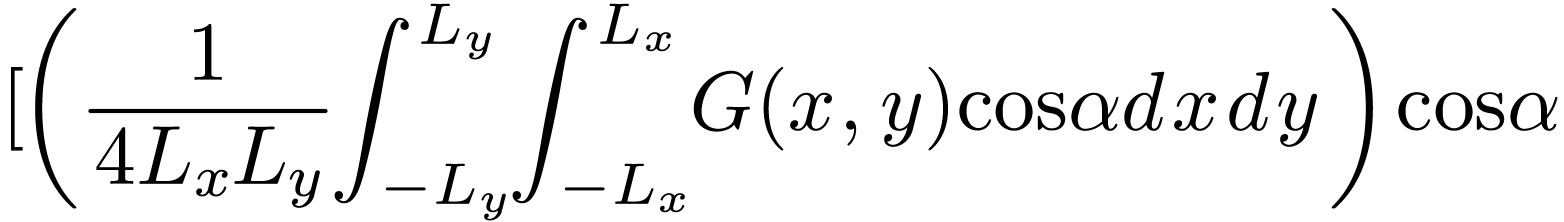

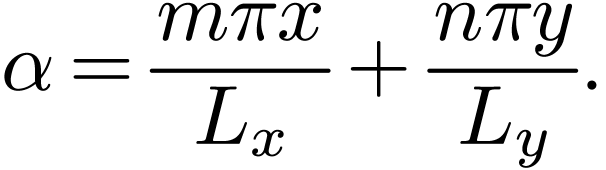

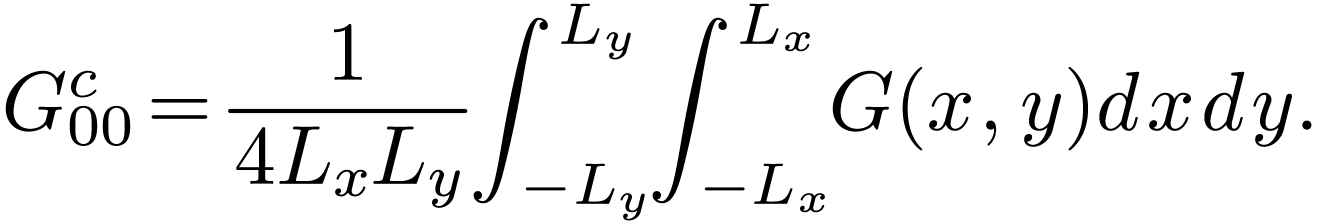

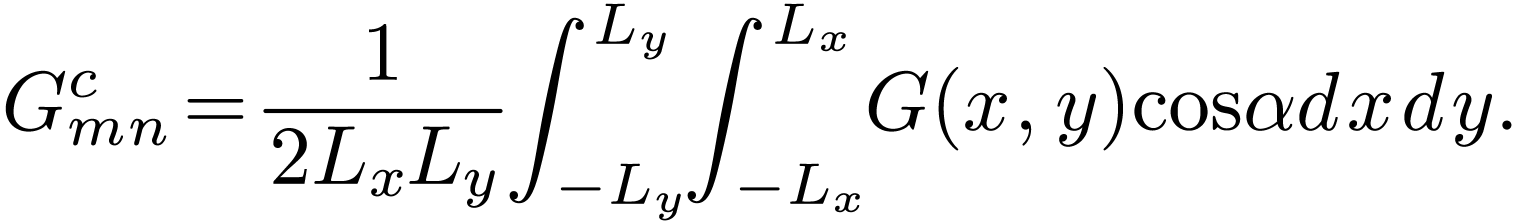

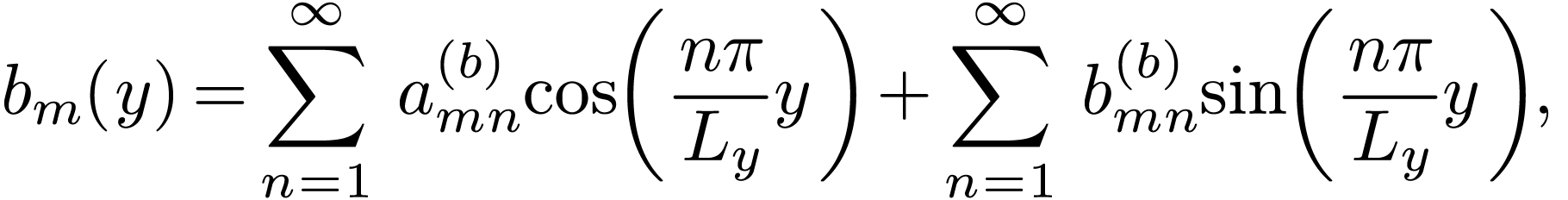

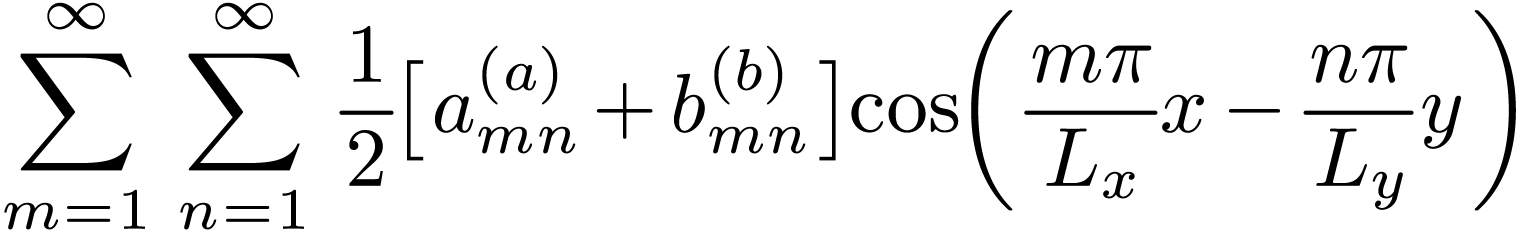

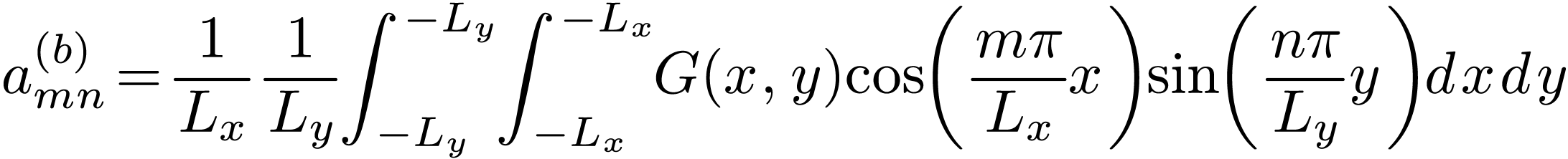

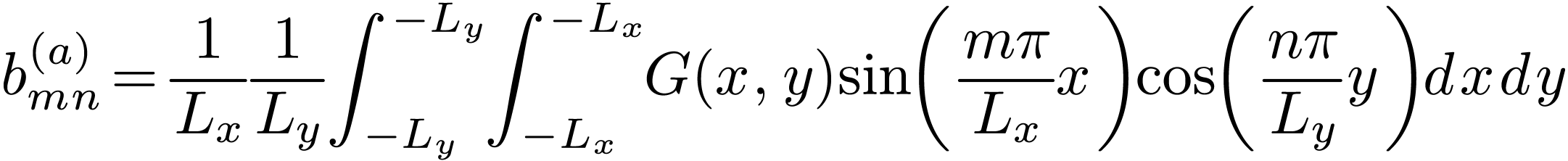

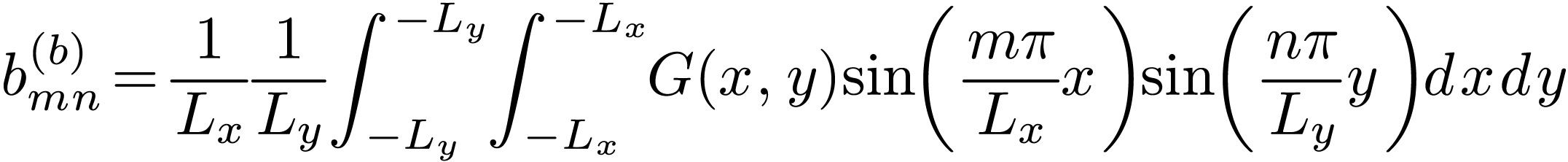

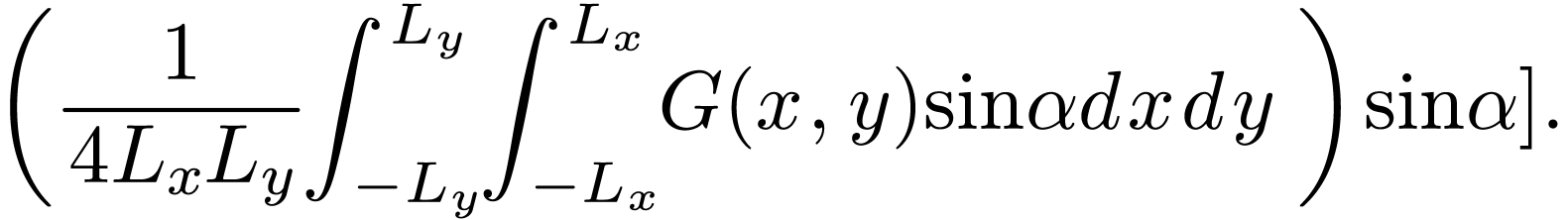

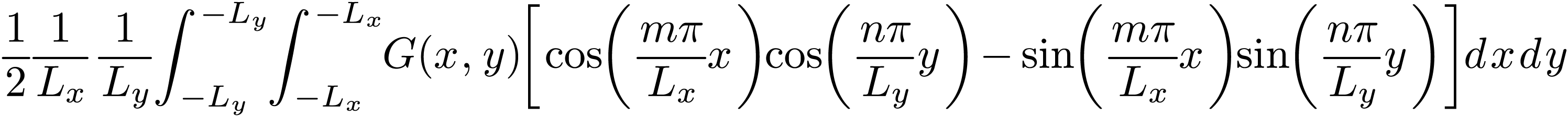

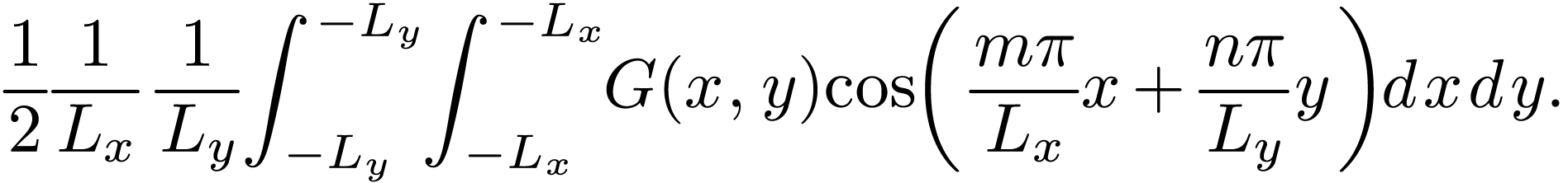

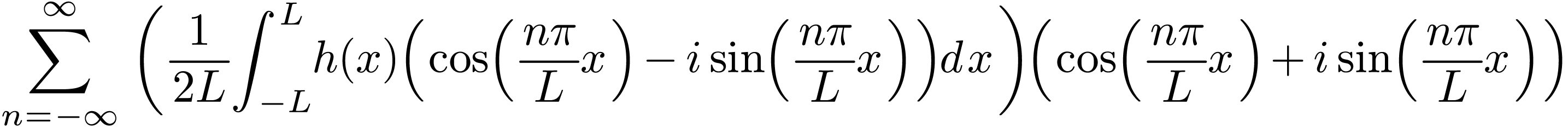

The formula for expanding a real-valued two-dimensional function  in terms of basis functions

in terms of basis functions  and

and  can be readily recovered from Eqs. (120)

and (119). For notation ease, define

can be readily recovered from Eqs. (120)

and (119). For notation ease, define

|

(121) |

Then Eq. (120) is written as

Sine  is assumed to be real-valued, the imaginary

parts of the above expression will cancel each other. Therefore, the

above expansion is simplified to

is assumed to be real-valued, the imaginary

parts of the above expression will cancel each other. Therefore, the

above expansion is simplified to

This is a compact Fouier expansion for 2D real-valued function.

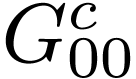

Furthermore, noting that  term is equal to

term is equal to  term, the above expansion can be further reduced to

term, the above expansion can be further reduced to

with

|

(124) |

and the other coefficients given by

|

(125) |

|

(126) |

Here the range of  is reduced to

is reduced to  . In this case, we have an edge case,

. In this case, we have an edge case,  , that needs special treatment. We

see that allowing the index runing from

, that needs special treatment. We

see that allowing the index runing from  to

to  has the advantage of that there are no edge cases

that needs special treatment.

has the advantage of that there are no edge cases

that needs special treatment.

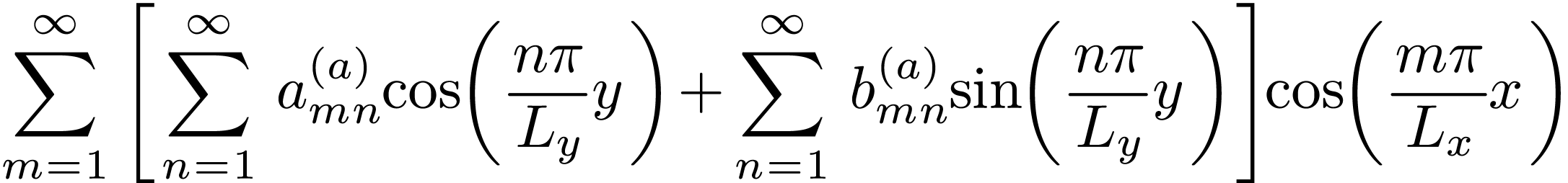

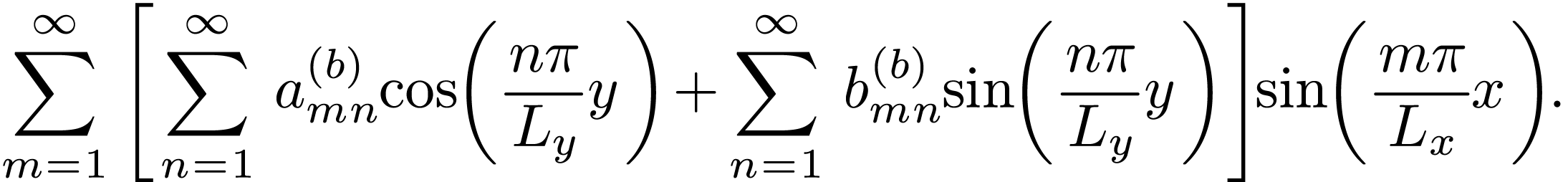

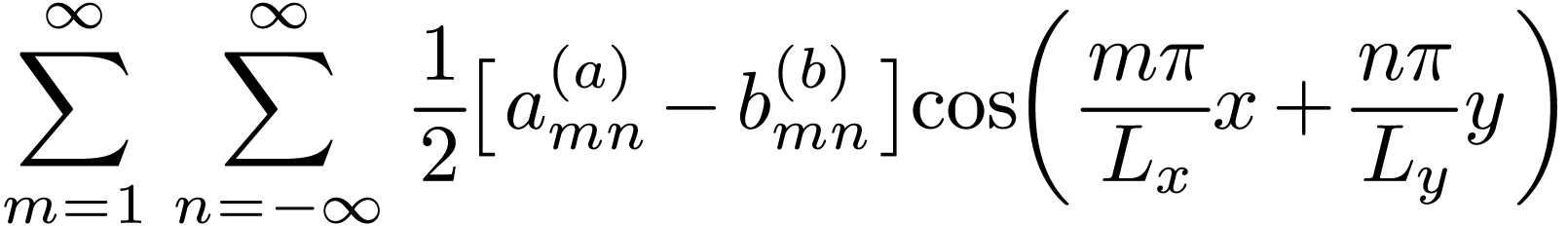

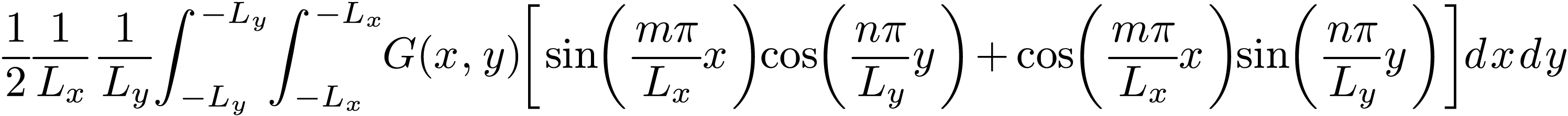

We see that the extension of Fourier series from one-dimension case to

two-dimension case is straightforward when expressed in terms of the

complex exponential function  .

However, if we use

.

However, if we use  ,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  as basis functions, the derivation of the

two-dimensional Fourier series of

as basis functions, the derivation of the

two-dimensional Fourier series of  is a little

complicated (product-to-sum trigonometric identities are involved to

simplify the results). Let's see the derivation. A two-dimensional

function

is a little

complicated (product-to-sum trigonometric identities are involved to

simplify the results). Let's see the derivation. A two-dimensional

function  can be first expanded as Fourier series

about

can be first expanded as Fourier series

about  ,

,

|

(127) |

(the zero-frequency component is dropped, will take it back later) and

then the two coefficients  and

and  can be further expanded as Fourier series about

can be further expanded as Fourier series about  ,

,

|

(128) |

|

(129) |

(the zero-frequency component is dropped, will take it back later) Substituting Eq. (128) and (129) into Eq. (127), we obtain

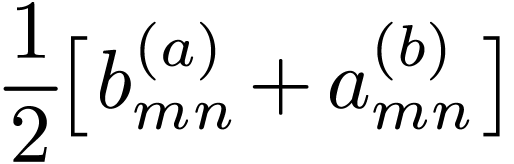

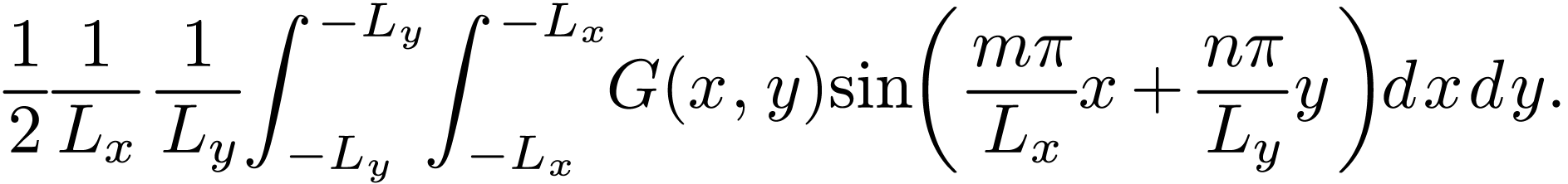

Using the product-to-sum trigonometric identities, equation (130) is written

which can be organized as

The coefficients appearing above are written as

|

(132) |

|

(133) |

|

(134) |

|

(135) |

|

(136) |

|

(137) |

Noting that  , and

, and  and

and  , then Eq.

(131) can be written as

, then Eq.

(131) can be written as

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The coefficients can be further written as

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Then comes the drudgery to handle the special cases of  and/or

and/or  . The final results

are identical to Eqs. (123)-(126). This kind

of derivation is also discussed in my notes on mega code.

. The final results

are identical to Eqs. (123)-(126). This kind

of derivation is also discussed in my notes on mega code.

The following is about a specific FFT subroutine provided by the Numerical recipes book[2]. This is not a general case.

The input and output of the DFT are usually complex numbers. In the

implementation of FFT algorithm provided by Numerical recipes book[2], to avoid using complex numbers, the algorithm adopts the

real number representation of the complex numbers. In this scheme, two

elements of a real number array are used to store one complex number. To

store a complex array “cdata” of length  , we will need a real number array

“rdata” of length

, we will need a real number array

“rdata” of length  .

The first elements of array “rdata” will contain the real

part of “cdata(1)”, the second elements of

“rdata” will contain the imaginary part of

“cdata(1)”, and so on.

.

The first elements of array “rdata” will contain the real

part of “cdata(1)”, the second elements of

“rdata” will contain the imaginary part of

“cdata(1)”, and so on.

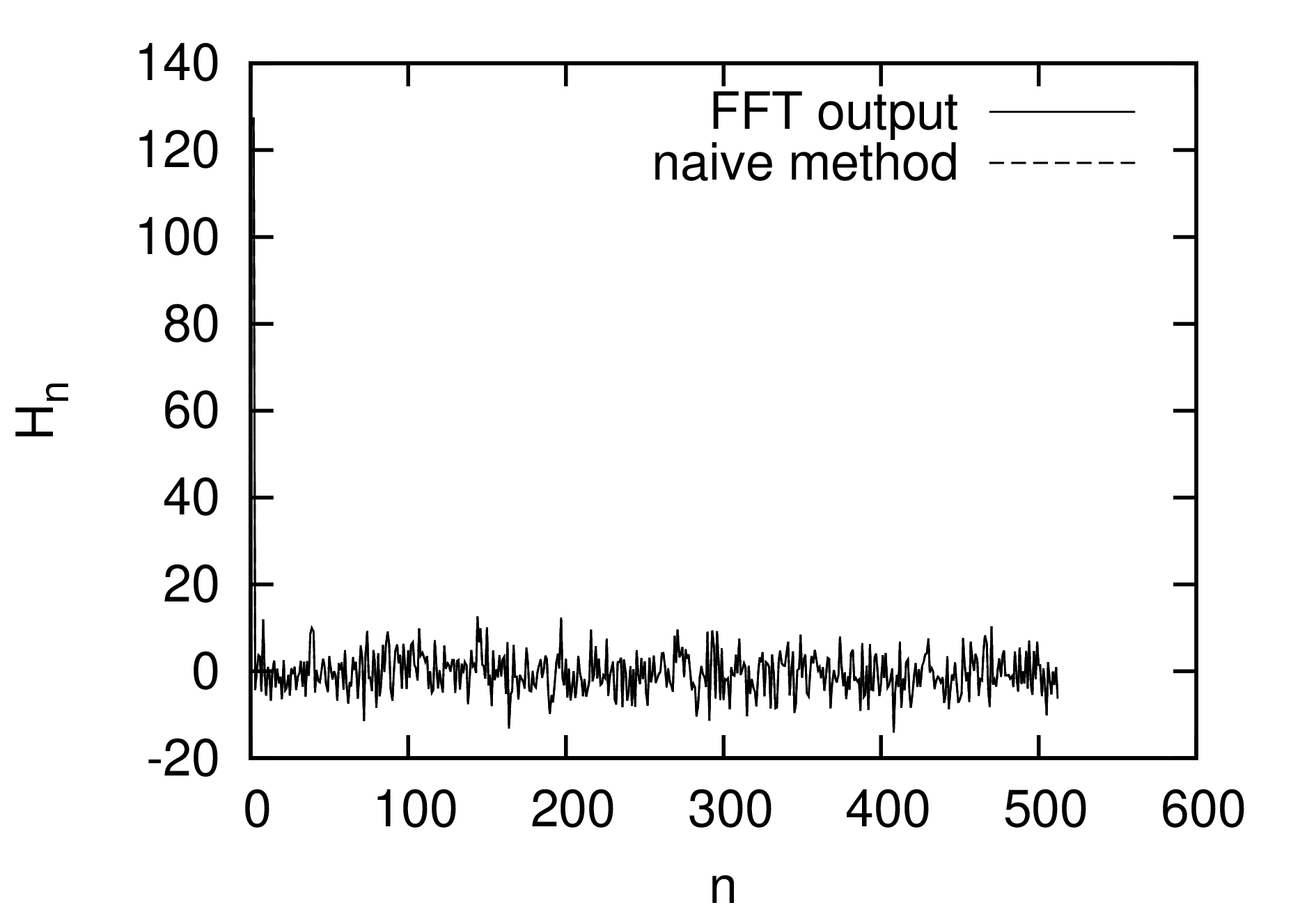

To test the correctness of the above statement, I generated a real

number array with length  by using a random

generating routine and calculate the DFT of the array with two methods.

The real array generated by the random generator are considered to be a

real number representation of a complex array with length

by using a random

generating routine and calculate the DFT of the array with two methods.

The real array generated by the random generator are considered to be a

real number representation of a complex array with length  . Using the real array as the input of the FFT

routine (the code in ~/project_new/fft). To check the correctness of my

understanding of the input and output of the FFT, I manually convert the

real number of length

. Using the real array as the input of the FFT

routine (the code in ~/project_new/fft). To check the correctness of my

understanding of the input and output of the FFT, I manually convert the

real number of length  to a complex array with

length

to a complex array with

length  , and use directly the

summation in Eq. () to calculate the DFT. The output I got is obviously

a complex array with length

, and use directly the

summation in Eq. () to calculate the DFT. The output I got is obviously

a complex array with length  .

Then I manually convert the complex array to a real number array of

length

.

Then I manually convert the complex array to a real number array of

length  and plot the output in Fig. 6

with dashed line. The results in Fig. 6 indicates the

results given by the FFT and the naive method used by me agree with each

other well. This proves that my understanding of the input and output of

FFT (especially the storage arrangement) is correct.

and plot the output in Fig. 6

with dashed line. The results in Fig. 6 indicates the

results given by the FFT and the naive method used by me agree with each

other well. This proves that my understanding of the input and output of

FFT (especially the storage arrangement) is correct.

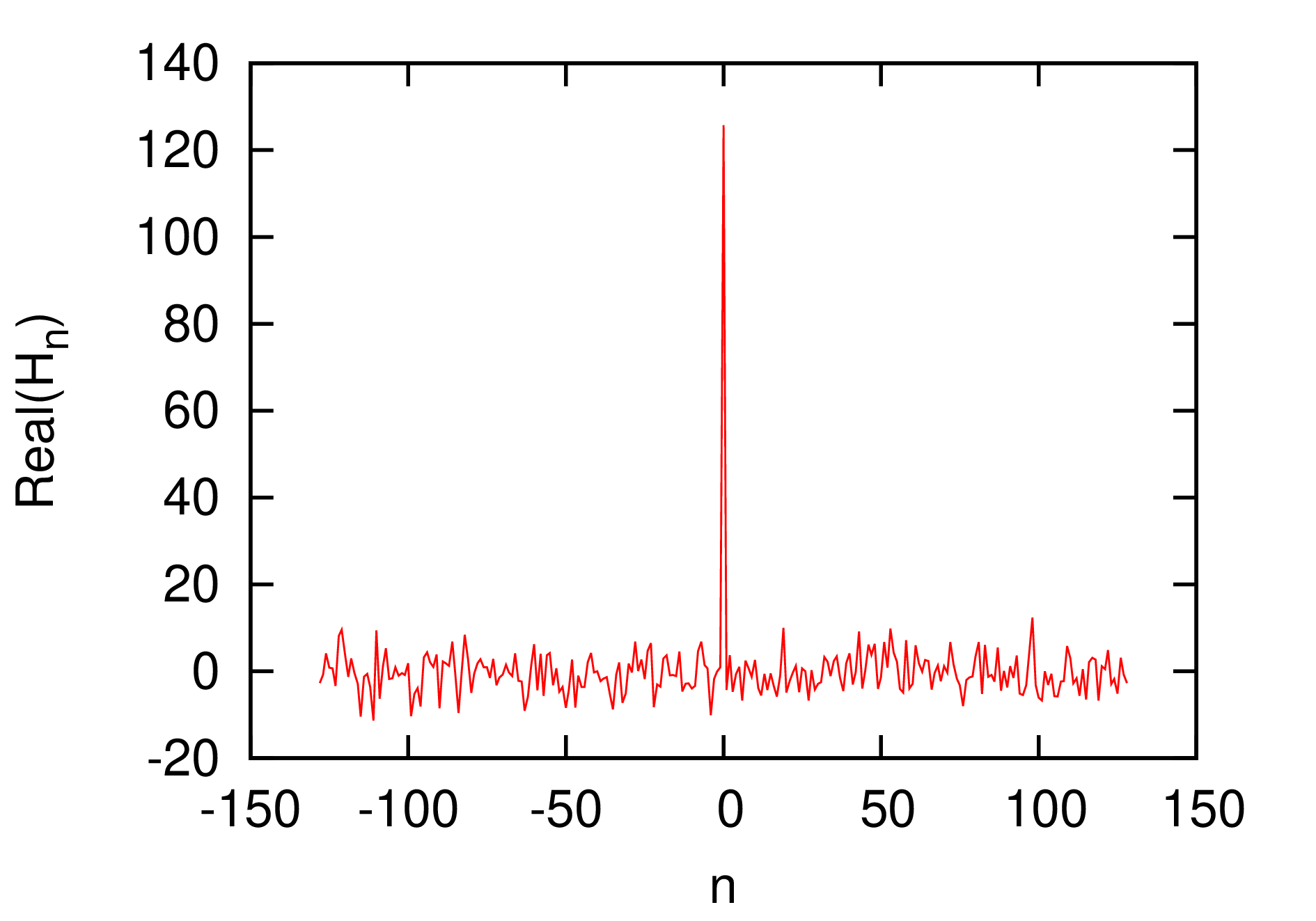

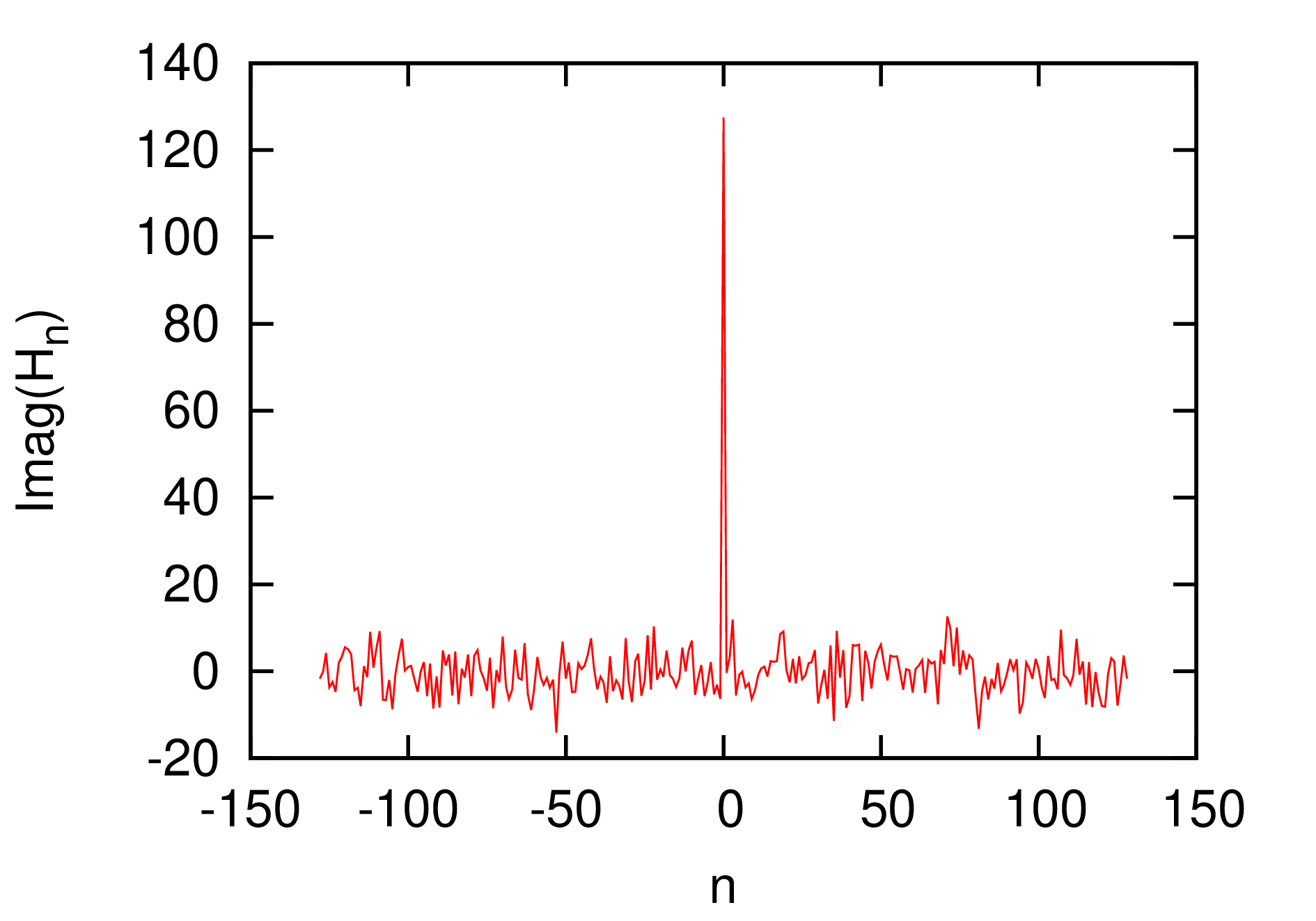

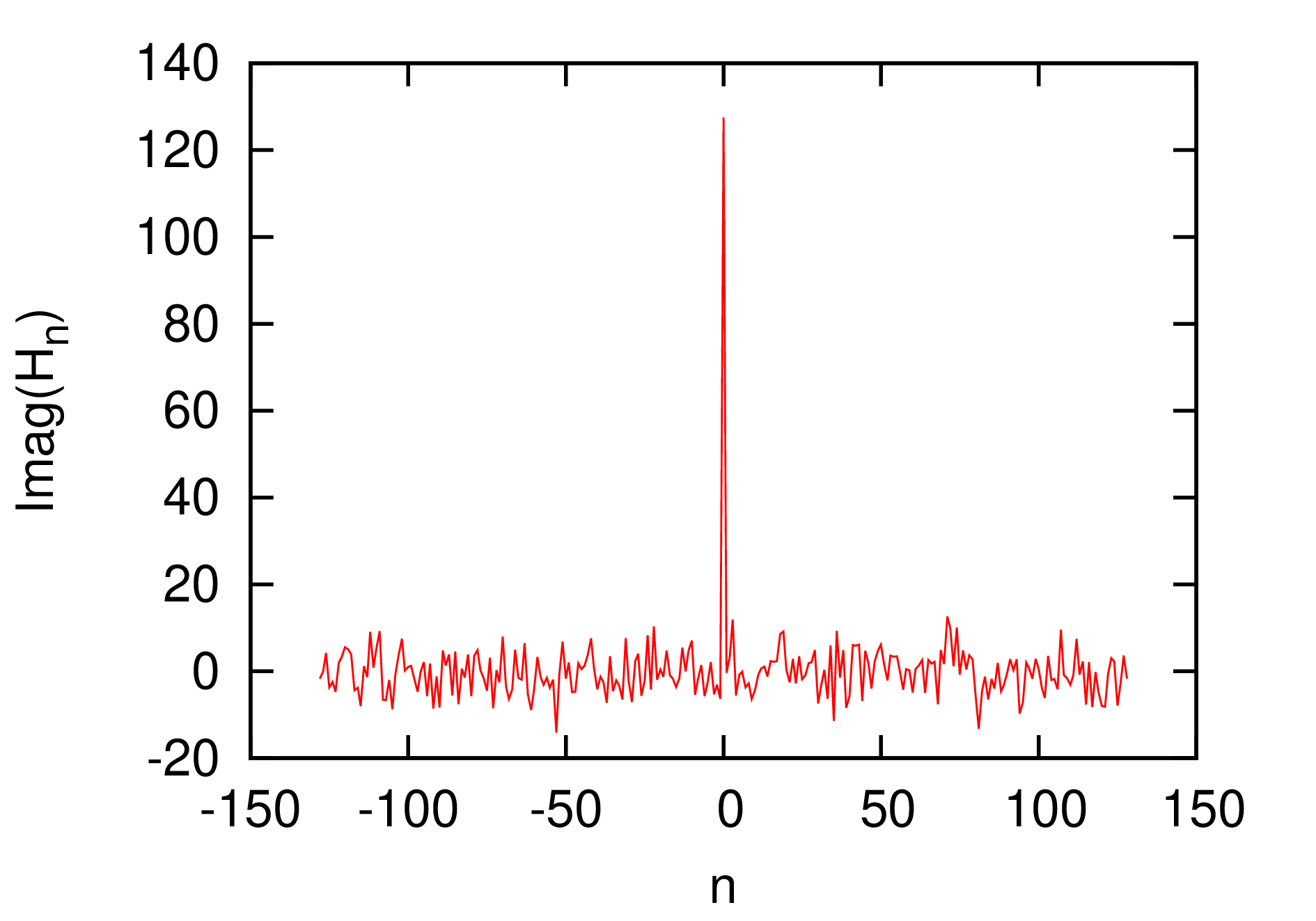

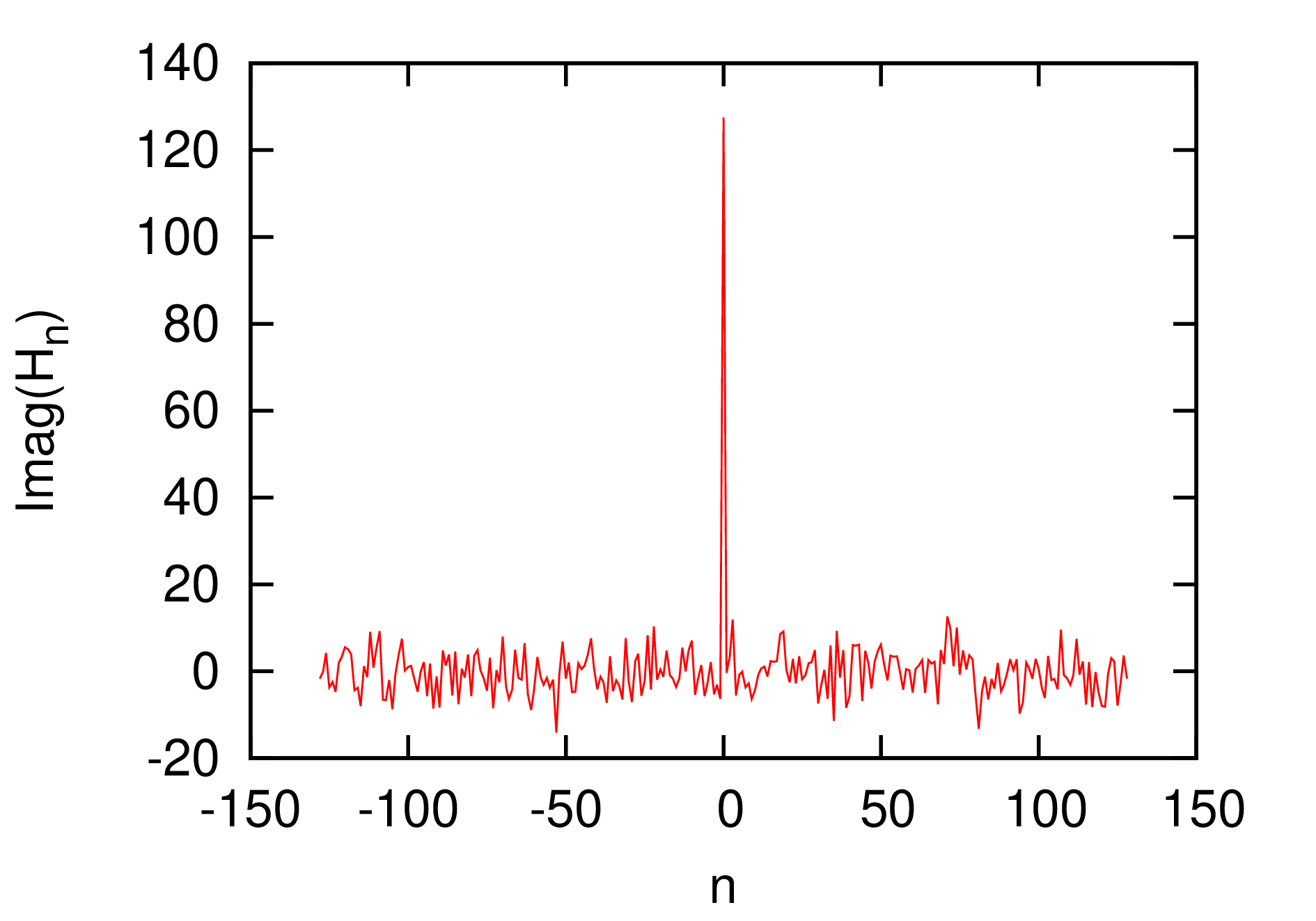

To clearly show the output of FFT, we recover the real and imaginary part of DFT from the output of FFT and plots the data as a function of their corresponding frequency. The results are given in Fig. 7.

|

Figure 7. The real (left) and

imaginary (right) part of the discrete Fourier transformation as

a function of the frequency. The point |

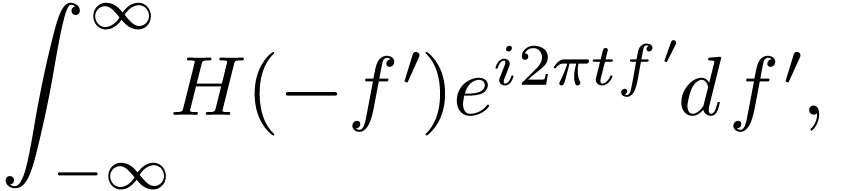

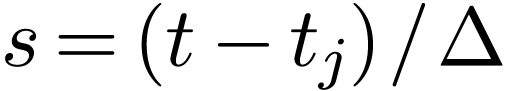

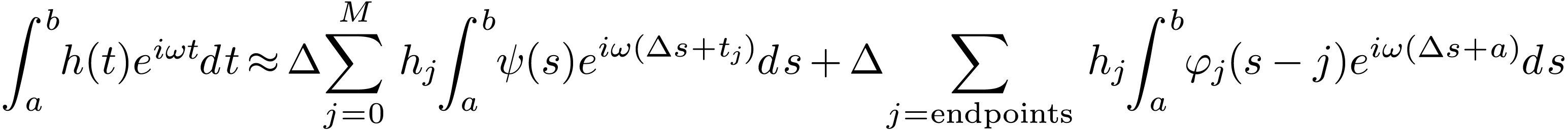

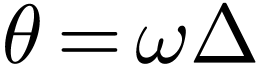

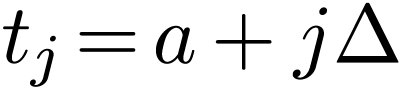

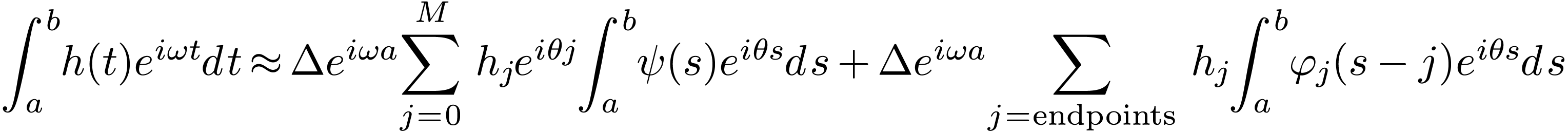

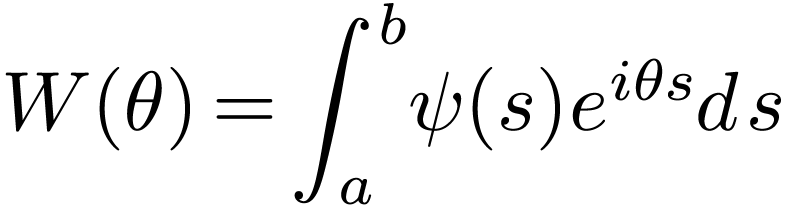

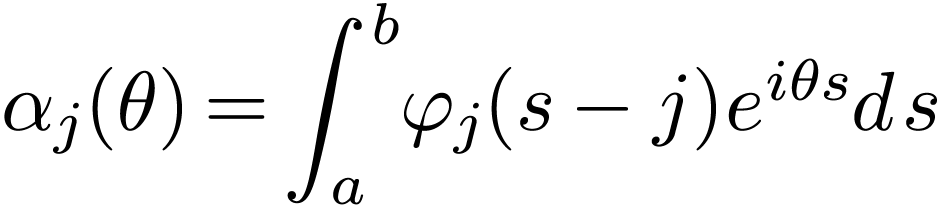

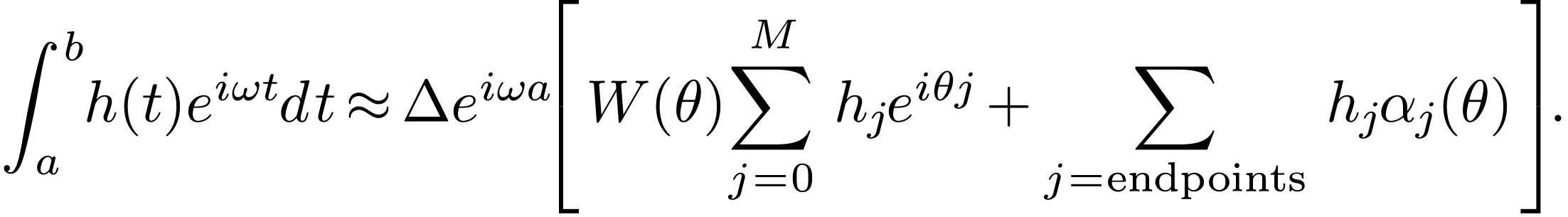

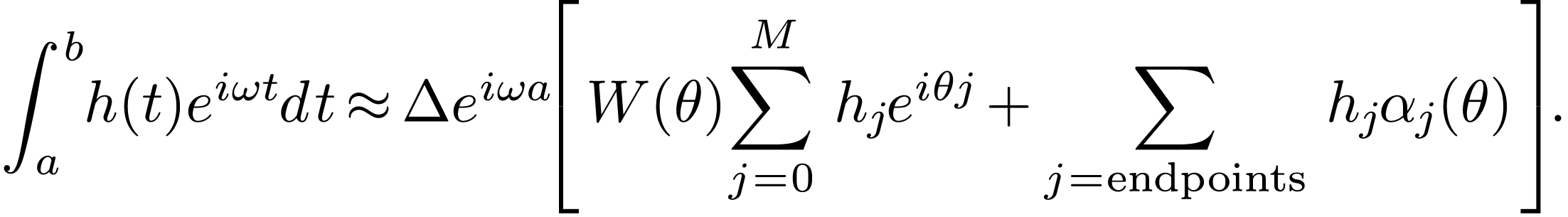

Consider the calculation of the following integral:

|

(141) |

Divide the interval  into

into  uniform sub-intervals and define

uniform sub-intervals and define

|

(142) |

Then the integration in Eq. (141) can be approximated as

|

(143) |

Define  with integer

with integer  and

and

. Consider the calculation of

. Consider the calculation of

. Using Eq. (143),

we obtain

. Using Eq. (143),

we obtain

Equation (145) indicates the value of the integration  can be obtained by calculating the discrete Fourier

transformation of

can be obtained by calculating the discrete Fourier

transformation of  . However,

as discussed in Ref. [2], equation (145) is

not recommended for practical use because the oscillatory nature of the

integral will make Eq. (145) become systematically

inaccurate as

. However,

as discussed in Ref. [2], equation (145) is

not recommended for practical use because the oscillatory nature of the

integral will make Eq. (145) become systematically

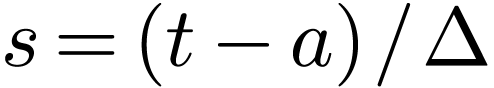

inaccurate as  increases. Next, consider a new

method, in which

increases. Next, consider a new

method, in which  is expanded as

is expanded as

|

(146) |

Apply the integral operator to both sides of Eq.

(146), we obtain

to both sides of Eq.

(146), we obtain

|

(147) |

Make the change of variables  in the first

integral and

in the first

integral and  in the second integral, the above

equation is written as

in the second integral, the above

equation is written as

|

(148) |

Define  and make use of

and make use of  , the above equation is written as

, the above equation is written as

|

(149) |

Define

|

(150) |

|

(151) |

Then Eq. (149) is written as

|

(152) |

|