is

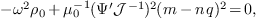

governed by the momentum equation

is

governed by the momentum equation

|

Abstract

This note discusses the linear ideal magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) theory of tokamak plasmas. This note also serves as a document for the GTAW code (General Tokamak Alfvén Waves code), which is a Fortran code calculating Alfven eigenmodes in realistic tokamak geometries.

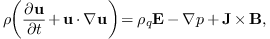

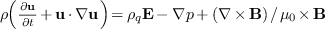

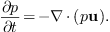

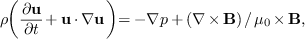

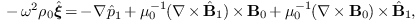

The time evolution of the fluid velocity  is

governed by the momentum equation

is

governed by the momentum equation

|

(1) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and  are mass density, charge density, thermal pressure, current density,

electric field, and magnetic field, respectively. The time evolution of

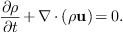

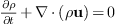

the mass density

are mass density, charge density, thermal pressure, current density,

electric field, and magnetic field, respectively. The time evolution of

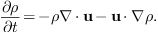

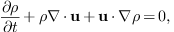

the mass density  is governed by the mass

continuity equation

is governed by the mass

continuity equation

|

(2) |

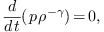

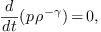

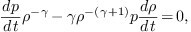

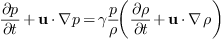

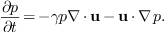

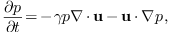

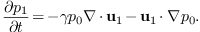

The time evolution equation for pressure  is

given by the equation of state

is

given by the equation of state

|

(3) |

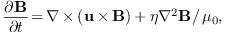

where  is the ratio of specific heats. The time

evolution of

is the ratio of specific heats. The time

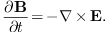

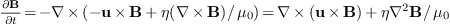

evolution of  is given by Faraday's law

is given by Faraday's law

|

(4) |

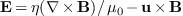

The current density  can be considered as a

derived quantity, which is defined through Ampere's law (the

displacement current being neglected)

can be considered as a

derived quantity, which is defined through Ampere's law (the

displacement current being neglected)

|

(5) |

The electric field  is considered to be a derived

quantity, which is defined through Ohm's law

is considered to be a derived

quantity, which is defined through Ohm's law

|

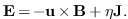

(6) |

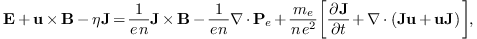

The charge density  can be considered to be a

derived quantity, which is defined through Poisson's equation,

can be considered to be a

derived quantity, which is defined through Poisson's equation,

|

(7) |

The above equations constitute a closed set of equations for the time

evolution of four quantities, namely,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  (the

electric field

(the

electric field  , current density

, current density  , and charge density

, and charge density  are eliminated

by using Eqs. (5), (6), and (6)).

In addition, there is an equation governing the spatial structure of the

magnetic field, namely

are eliminated

by using Eqs. (5), (6), and (6)).

In addition, there is an equation governing the spatial structure of the

magnetic field, namely

|

(8) |

In summary, the MHD equations can be categorized into three groups of equations, namely[1],

Evolution equations for base quantities  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and  :

:

,

,

,

,

Equation of constraint:  .

.

Definitions: (i.e., they are considered to be derived quantities.)

,

,

,

,

.

.

The electrical field term  in the momentum

equation (1) is usually neglected because this term is

usually much smaller than other terms for low-frequency phenomena in

tokamak plasmas (quasi-neutral approximation).

in the momentum

equation (1) is usually neglected because this term is

usually much smaller than other terms for low-frequency phenomena in

tokamak plasmas (quasi-neutral approximation).

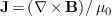

It is well known that the divergence of Faraday's law (4) is written

|

(9) |

which implies that  will hold in later time if it

is satisfied at the initial time.

will hold in later time if it

is satisfied at the initial time.

Because the displacement current is neglected in Ampere's law, the divergence of Ampere's law is written

|

(10) |

On the other hand, the charge density is defined through Poisson's equation, Eq. (7), i.e.,

which indicates that the charge density  is

usually time dependent, i.e.,

is

usually time dependent, i.e.,  . Therefore the

charge conservation is not guaranteed in this framework. This

inconsistency is obviously due to the fact that we neglect the

displacement current

. Therefore the

charge conservation is not guaranteed in this framework. This

inconsistency is obviously due to the fact that we neglect the

displacement current  in Ampere's law. Since, for

low frequency phenomena, the displacement current

in Ampere's law. Since, for

low frequency phenomena, the displacement current  term is usually much smaller than the the conducting current

term is usually much smaller than the the conducting current  , neglecting the displacement current term induces only

small errors in calculating

, neglecting the displacement current term induces only

small errors in calculating  by using Eq. (5).

by using Eq. (5).

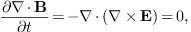

Referece [2] gives a clear derivation of the generalized Ohm's law, which takes the following form

|

(12) |

where the first term on the right-hand side is called the “Hall term”, the second term is the electron pressure term, and the third term is called the “electron inertia term” since it is proportional to the mass of electrons.

Note that both  and

and  are

the first-order moments, with

are

the first-order moments, with  being the weighted

sum of the first-order moment of electrons and ions while

being the weighted

sum of the first-order moment of electrons and ions while  being the difference between them. The generalized Ohm's

law is actually the difference between the electrons and ions

first-order moment equations. The generalized Ohm's law is an equation

that governs the time evolution of

being the difference between them. The generalized Ohm's

law is actually the difference between the electrons and ions

first-order moment equations. The generalized Ohm's law is an equation

that governs the time evolution of  . Also note

that Ampere's law, with the displacement current retained, is an

equation governing the time evolution of

. Also note

that Ampere's law, with the displacement current retained, is an

equation governing the time evolution of  .

However, in the approximation of the resistive MHD, the time derivative

term

.

However, in the approximation of the resistive MHD, the time derivative

term  is dropped in Ampere's law and and

is dropped in Ampere's law and and  is dropped in Ohm's law. In this approximation, Ohm's

law is directly solved to determine

is dropped in Ohm's law. In this approximation, Ohm's

law is directly solved to determine  and Ampere's

law is directly solved to determine

and Ampere's

law is directly solved to determine  .

.

from equation of state

from equation of state

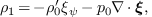

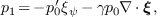

The equation of state (3) involves three physical

quantities, namely  ,

,  , and

, and

. It turns out that the continuity equation can

be used in the equation to eliminate

. It turns out that the continuity equation can

be used in the equation to eliminate  . The

equation of state

. The

equation of state

|

(13) |

can be written as

|

(14) |

which simplifies to

|

(15) |

Expand the total derivative, giving

|

(16) |

Using the mass continuity equation to eliminate  in the above equation gives

in the above equation gives

|

(17) |

This equation governs the time evolution of the pressure. A way to

memorize this equation is that, if  , the equation

will take the same form as a continuity equation, i.e.,

, the equation

will take the same form as a continuity equation, i.e.,

|

(18) |

For the convenience of reference, the MHD equations discussed above are

summarized here. The time evolution of the four quantities, namely  ,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  , are governed respectively by the following

four equations:

, are governed respectively by the following

four equations:

|

(19) |

|

(20) |

|

(21) |

|

(22) |

Note that only Eq. (19) involves the resistivity  . When

. When  , the above system is called

ideal MHD equations.

, the above system is called

ideal MHD equations.

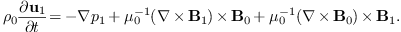

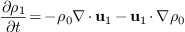

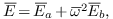

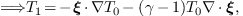

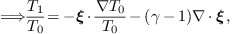

Next, consider the linearized version of the ideal MHD equations. Use

,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  to denote the equilibrium fluid velocity,

magnetic field, plasma pressure, and mass density, respectively. Use

to denote the equilibrium fluid velocity,

magnetic field, plasma pressure, and mass density, respectively. Use

,

,  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  to denote the perturbed fluid velocity,

magnetic field, plasma pressure, and mass density, respectively.

Consider only the case that there is no equilibrium flow, i.e.,

to denote the perturbed fluid velocity,

magnetic field, plasma pressure, and mass density, respectively.

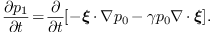

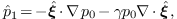

Consider only the case that there is no equilibrium flow, i.e.,  . From Eq. (21), the linearized equation

for the time evolution of the perturbed pressure is written

. From Eq. (21), the linearized equation

for the time evolution of the perturbed pressure is written

|

(23) |

The linearized momentum equation is written

|

(24) |

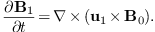

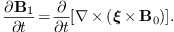

The linearized induction equation is written

|

(25) |

These three equations constitute a closed system for  ,

,

, and

, and  . Note that the

linearized equation for the perturbed mass density

. Note that the

linearized equation for the perturbed mass density

|

(26) |

is not needed when solving the system of equations (23)-(25) because  does not appear in

equations (23)-(25).

does not appear in

equations (23)-(25).

In dealing with the linear case of MHD theory, it is convenient to

introduce the plasma displacement vector  , which

is defined through the following equation

, which

is defined through the following equation

|

(27) |

Using the definition of  and the fact that the

equilibrium quantities are independent of time, the linearized induction

equation (25) is written

and the fact that the

equilibrium quantities are independent of time, the linearized induction

equation (25) is written

|

(28) |

Similarly, the equation for the perturbed pressure [Eq. (23)] is written

|

(29) |

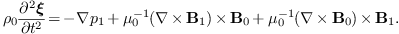

In terms of the displacement vector, the linearized momentum equation (24) is written

|

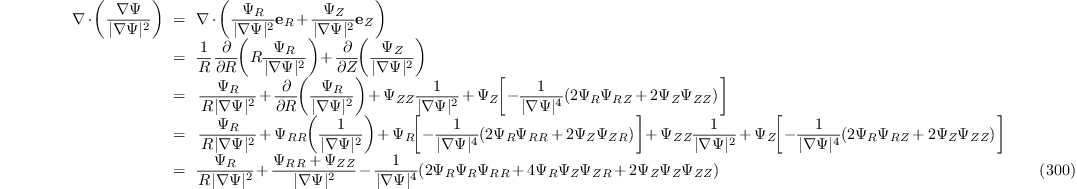

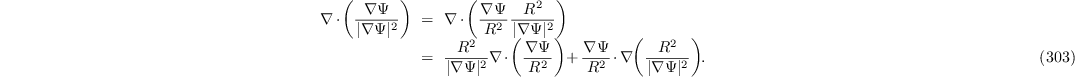

(30) |

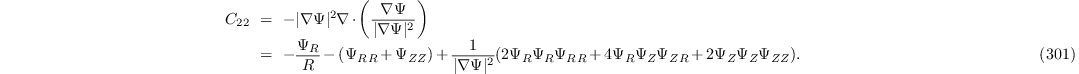

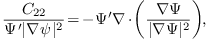

Equations (28), (29), and (30)

constitute a closed system for  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  .

.

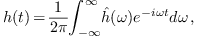

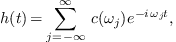

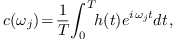

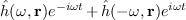

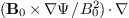

A general perturbation can be written

|

(31) |

where the coefficient  is given by the Fourier

transformation of

is given by the Fourier

transformation of  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

|

(32) |

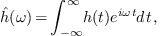

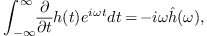

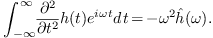

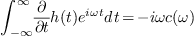

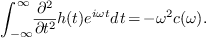

Using the definition of the Fourier transformtion, it is ready to prove that

|

(33) |

and

|

(34) |

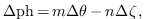

Performing Fourier transformation (in time) on both sides of the the linearized momentum equation (30) and noting that the equilibrium quantities are all independent of time, we obtain

|

(35) |

where use has been made of the property in Eq. (34). Similarly, the Fourier transformation of the equations of state (29) is written

|

(36) |

and the Fourier transformation of Faraday's law (28) is written

|

(37) |

Equations (35)-(37) agree with Eqs. (12)-(14)

in Cheng's paper[3]. They constitute a closed set of

equations for  ,

,  , and

, and  . In the next section, for notation ease, the hat on

. In the next section, for notation ease, the hat on

,

,  , and

, and  will be omitted, with the understanding that they are the Fourier

transformations of the corresponding quantities.

will be omitted, with the understanding that they are the Fourier

transformations of the corresponding quantities.

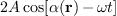

In dealing with eigenmodes, we ususally encounter discrete frequency

perturbations, i.e.,  is periodic function of

is periodic function of

so that they contian only discrete frequency

components. In this case, the inverse Fourier transformtion in Eq. (31) is replaced by the Fourier series, i.e.,

so that they contian only discrete frequency

components. In this case, the inverse Fourier transformtion in Eq. (31) is replaced by the Fourier series, i.e.,

|

(38) |

where the coefficients  are given by

are given by

|

(39) |

with  and

and  being the

period of

being the

period of  (

( is larger

enough so that

is larger

enough so that  is very small compared with

frequency we are interested). The relation between

is very small compared with

frequency we are interested). The relation between  and

and  given by Eqs. (33) and (34) also applies to the relation between

given by Eqs. (33) and (34) also applies to the relation between  and

and  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

|

(40) |

and

|

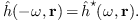

(41) |

Using the transformtion given by Eq. (39) on Eqs. (28), (29), and (30), respectively, we obtain the same equation as Eqs. (35)-(37).

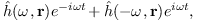

A general perturbation is given by Eq. (31), which is

composed of infinit single-frequency perturbation of the form  . It is obvious that a general perturbation can also be

considered to be composed of single frequency perturbation of the form

. It is obvious that a general perturbation can also be

considered to be composed of single frequency perturbation of the form

|

(42) |

In this case the range of  is limited in

is limited in  . Because a physical quanty is always a real function,

. Because a physical quanty is always a real function,

in the above should be a real function. It is

ready to prove that the Fourier transformation of

in the above should be a real function. It is

ready to prove that the Fourier transformation of  has the following symmetry in frequency domain:

has the following symmetry in frequency domain:

|

(43) |

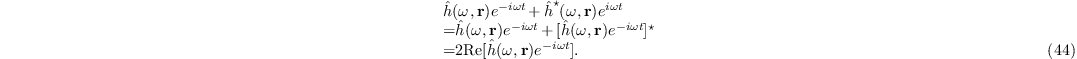

Uisng this, the expression (42) is written

Writing  , where

, where  and

and  are real numbers, then the above expression is

written as

are real numbers, then the above expression is

written as

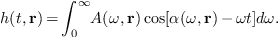

Using expression (45), the Fourier transformation is written

|

(46) |

If  satisfies the eigenmode equations (35)-(37), then it is ready to verify that

satisfies the eigenmode equations (35)-(37), then it is ready to verify that  is also a solution to the equations. Then Eq. (43) implies

that

is also a solution to the equations. Then Eq. (43) implies

that  is also a slution to the equations.

Therefore

is also a slution to the equations.

Therefore  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  , is a

solution to the linear equations (28), (29),

and (30). This tell us how to construct a real (physical)

eigenmode from the complex funtion

, is a

solution to the linear equations (28), (29),

and (30). This tell us how to construct a real (physical)

eigenmode from the complex funtion  , i.e., the

real part of

, i.e., the

real part of  is a physical eigenmode. Note that

it is the real part of

is a physical eigenmode. Note that

it is the real part of  , instead of the real part

of

, instead of the real part

of  , that is a physical eigenmode.

, that is a physical eigenmode.

Note that  is a real number by the definition of

Fourier transformation. However, strictly speaking, the above Fourier

transformation should be replaced by Laplace transformation. In this

case,

is a real number by the definition of

Fourier transformation. However, strictly speaking, the above Fourier

transformation should be replaced by Laplace transformation. In this

case,  is a complex number. In the following, we

will assume that we are using Laplace transformation, instead of Fourier

transformation. In the following section, we will prove that the

eigenvalue

is a complex number. In the following, we

will assume that we are using Laplace transformation, instead of Fourier

transformation. In the following section, we will prove that the

eigenvalue  of the ideal MHD system must be a

real number.

of the ideal MHD system must be a

real number.

Using Eqs. (36) and (37) to eliminate  and

and  from Eq. (35),

we obtain

from Eq. (35),

we obtain

|

(47) |

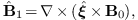

where  , the linear force operator, is given by

, the linear force operator, is given by

|

(48) |

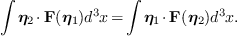

It can be proved that the linear force operator  is self-adjoint (or Hermitian) (I have never proven this), i.e., for any

two general functions

is self-adjoint (or Hermitian) (I have never proven this), i.e., for any

two general functions  and

and  that satisfy the same boundary condition, we have

that satisfy the same boundary condition, we have

|

(49) |

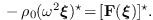

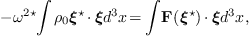

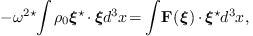

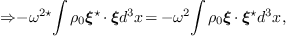

As a consequence of the self-adjointness, the eigenvalue,  , must be a real number. [Proof: Taking the complex

conjugate of Eq. (47), we obtain

, must be a real number. [Proof: Taking the complex

conjugate of Eq. (47), we obtain

|

(50) |

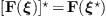

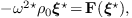

Note that the expression of  given in Eq. (48) have the property

given in Eq. (48) have the property  , Using this,

equation (50) is written

, Using this,

equation (50) is written

|

(51) |

Taking the scalar product of both sides of the above equation with  and integrating over the entire volume of the system,

gives

and integrating over the entire volume of the system,

gives

|

(52) |

Using the self-ajointness of  , the above equation

is written

, the above equation

is written

|

(53) |

|

(54) |

|

(55) |

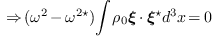

Since  is non-zero for any non-trivial

eigenfunction, it follows from Eq. (55) that

is non-zero for any non-trivial

eigenfunction, it follows from Eq. (55) that  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  must be a real number,

which implies that

must be a real number,

which implies that  is either purely real or

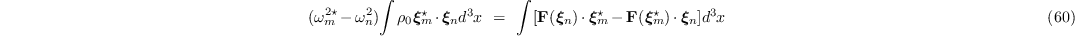

purely imaginary.] It can also be proved that two eigenfunctions of the

Hermitian operator corresponding to different eigenvalues are orthogonal

to each other. [Proof:

is either purely real or

purely imaginary.] It can also be proved that two eigenfunctions of the

Hermitian operator corresponding to different eigenvalues are orthogonal

to each other. [Proof:

|

(56) |

|

(57) |

Taking the scalar product of both sides of Eq. (56) with

and integrating over the entire volume of the

system, gives

and integrating over the entire volume of the

system, gives

|

(58) |

Taking the scalar product of both sides of Eq. (57) with

and integrating over the entire volume of the

system, gives

and integrating over the entire volume of the

system, gives

|

(59) |

Combining the above two equations, we obtain

Using the self-ajointness of  , we know the

right-hand side of Eq. (59) is zero. Thus Eq. (59)

is written

, we know the

right-hand side of Eq. (59) is zero. Thus Eq. (59)

is written

|

(61) |

Using  , the above equation is written

, the above equation is written

|

(62) |

Since we assume  , the above equation reduces to

, the above equation reduces to

|

(63) |

i.e.,  and

and  are orthogonal

to each other.]

are orthogonal

to each other.]

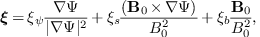

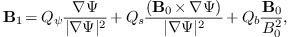

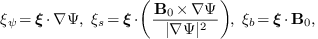

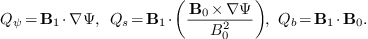

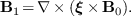

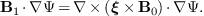

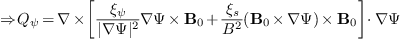

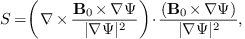

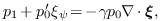

Next, we consider the form of the linearized MHD equations in toroidal devices (e.g. tokamak). In these devices, there exist magnetic surfaces. The motion of plasma along the surface and perpendicular to the surface are very different. Thus, it is useful to decompose the perturbed quantities into components lying on the surface and perpendicular to the surface. Following Ref. [3, 4], we write the displacement vector and perturbed magnetic field as

|

(64) |

and

|

(65) |

where  is the poloidal magnetic flux function

appearing in the GS equation (

is the poloidal magnetic flux function

appearing in the GS equation ( ). (In deriving the

eigenmode equation, we do not need the specific definition of

). (In deriving the

eigenmode equation, we do not need the specific definition of  . What we need is only that

. What we need is only that  is a

vector in the direction of

is a

vector in the direction of  and thus

and thus  is perpendicular to both

is perpendicular to both  and

and  ). Taking scalar product of the above two equations

with

). Taking scalar product of the above two equations

with  ,

,  , and

, and  , respectively, we obtain

, respectively, we obtain

|

(66) |

|

(67) |

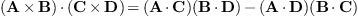

Next, we derive the component equations for the induction equation (37) and momentum equation (35). The derivation is straightforward but tedious. Those who are not interested in these details can skip them and read directly Sec. 3.7 for the final form of the component equations.

component of

induction equation

component of

induction equationThe induction equation is given by Eq. (37), i.e.,

|

(68) |

Next, consider the  component of the above

equation. Taking scalar product of the above equation with

component of the above

equation. Taking scalar product of the above equation with  , we obtain

, we obtain

|

(69) |

|

(70) |

|

(71) |

|

(72) |

|

(73) |

|

(74) |

|

(75) |

|

(76) |

|

(77) |

|

(78) |

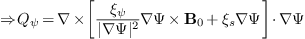

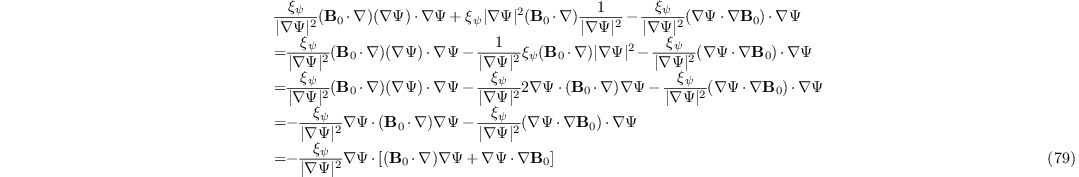

Excluding  terms, the terms on the right hand

side (r.h.s) of the above equation can be written

terms, the terms on the right hand

side (r.h.s) of the above equation can be written

Using  , we obtain

, we obtain

The r.h.s of the above equation is exactly the term appearing on the right-hand side of Eq. (79). Thus we obtain

|

(82) |

which agrees with Eq. (20) in Cheng's paper[3].

component of

induction equation

component of

induction equation

The  component of the induction equation is given

by

component of the induction equation is given

by

|

(83) |

which can be further written as

where

|

(85) |

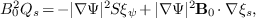

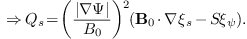

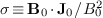

is the negative local magnetic shear. Using  ,

equation (84) is written as

,

equation (84) is written as

|

(86) |

|

(87) |

Eq. (87) agrees with Eq. (21) in Cheng's paper[3].

component of

induction equation

component of

induction equation

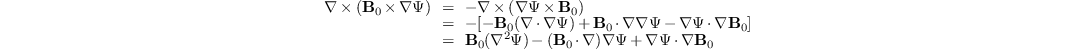

The component of the induction equation in the direction of  is written as

is written as

|

(88) |

|

(89) |

The term on right-hand side of the above equation is written as

Using this, the right-hand side of Eq. (89) is written as

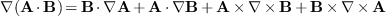

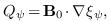

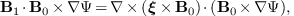

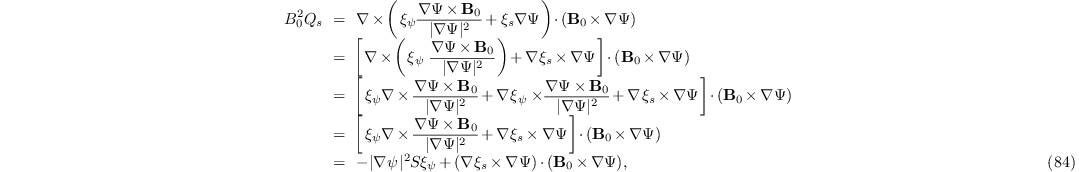

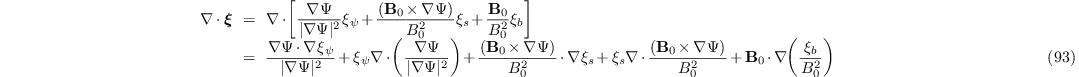

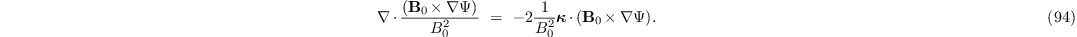

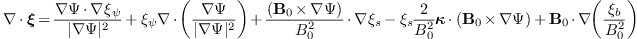

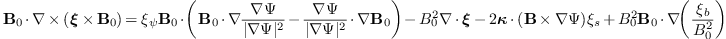

Before we try to simplify the above equation, we derive the expression

for the divergence of  , which is written as

, which is written as

It can be proved that the fourth term of the above equation can be written as (refer to (9.8) for the proof)

Then Eq. (93) is written as

|

(95) |

Eq. (95) agrees with Eq. (23) in Cheng's paper, but a  factor is missed in the fourth term of Cheng's

equation[3]. Using Eq. (95), Eq. (92)

is written as

factor is missed in the fourth term of Cheng's

equation[3]. Using Eq. (95), Eq. (92)

is written as

|

(96) |

It can be proved that

|

(97) |

(Refer to Sec. 9.10 for the proof.) Then Eq. (96) is written as

|

(98) |

and the component of the induction equation in the direction of  [Eq. (89)] is finally written as

[Eq. (89)] is finally written as

|

(99) |

Eq. (99) agrees with Eq. (22) in Cheng's paper[3].

The three components of the linearized momentum equation can be obtained

by taking scalar product of Eq. (35) with  ,

,

, and

, and  , respectively. We

first consider the

, respectively. We

first consider the  component of the momentum

equation, which is written as

component of the momentum

equation, which is written as

|

(100) |

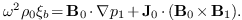

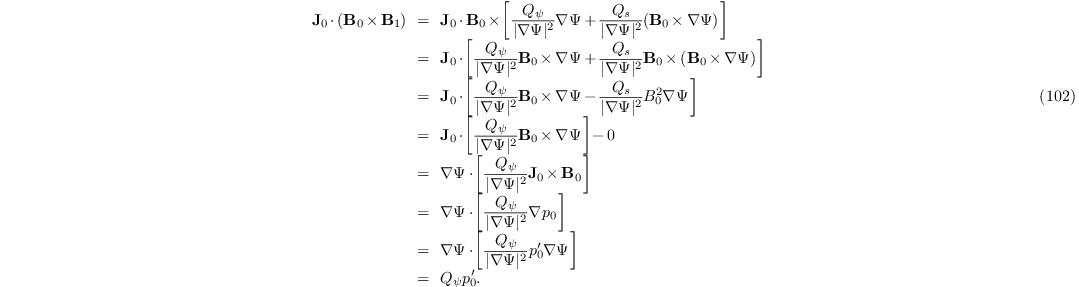

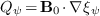

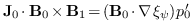

i.e.,

|

(101) |

The last term on the right-hand side of Eq. (101) can be written as

where  . Using Eq. (82), i.e.,

. Using Eq. (82), i.e.,  , the above equation is written as

, the above equation is written as

|

(103) |

Substituting Eq. (103) into Eq. (101) gives

|

(104) |

Using  in the above equation gives

in the above equation gives

|

(105) |

which agrees with Eq. (19) in Cheng's paper[3].

component of

momentum equation

component of

momentum equation

Next we consider the radial component of the momentum equation. Taking

scalar product of the momentum equation with  , we

obtain

, we

obtain

|

(106) |

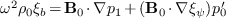

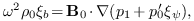

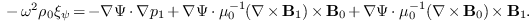

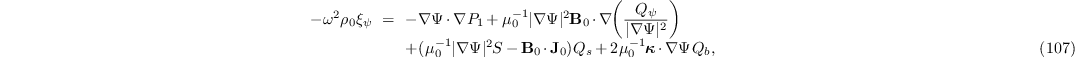

After some algebra (the details are given in Sec. (9.5)), Eq. (106) is written

where

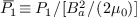

|

(108) |

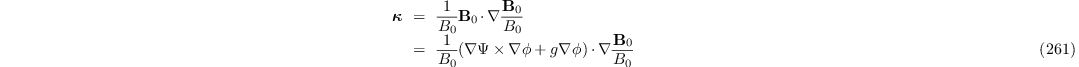

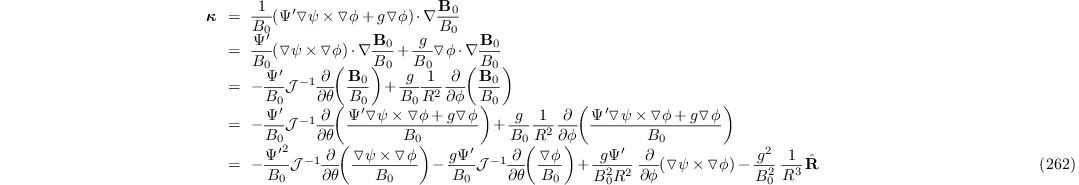

and  is the magnetic field curvature with

is the magnetic field curvature with  the unit vector along equilibrium magnetic field.

Equation (107) agrees with Eq. (17) in Cheng's paper[3]. In passing, let us examine the physical meaning of

the unit vector along equilibrium magnetic field.

Equation (107) agrees with Eq. (17) in Cheng's paper[3]. In passing, let us examine the physical meaning of  defined by (108). In linear

approximation, we have

defined by (108). In linear

approximation, we have

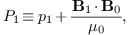

This indicates the perturbation in the square of the magnetic strength

is  . Therefore, the perturbation in magnetic

pressure is written

. Therefore, the perturbation in magnetic

pressure is written

|

(110) |

which indicate  defined by Eq. (108)

is the total perturbation in the thermal and magnetic pressure.

defined by Eq. (108)

is the total perturbation in the thermal and magnetic pressure.

component of

momentum equation

component of

momentum equation

The  component of the linearized momentum

equation is written

component of the linearized momentum

equation is written

|

(111) |

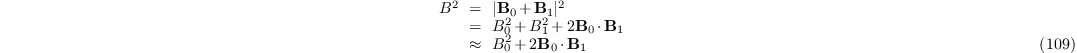

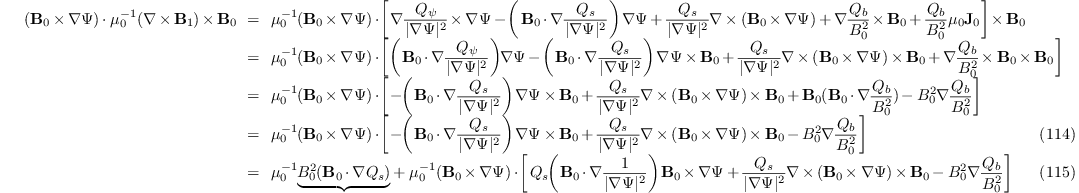

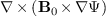

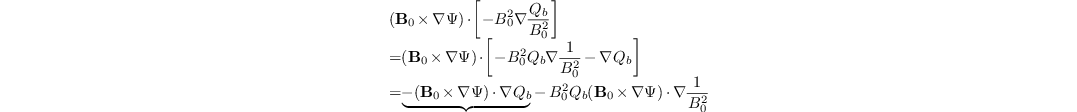

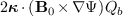

The last term of Eq. (111) is written

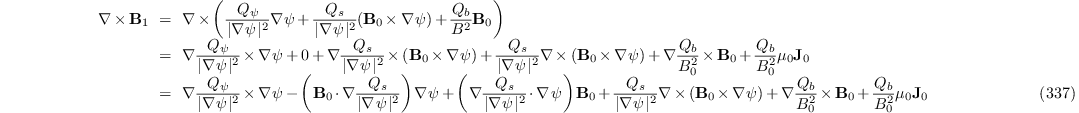

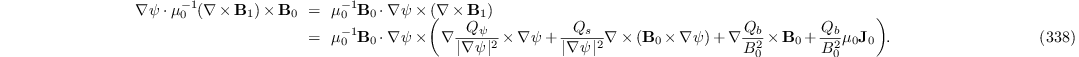

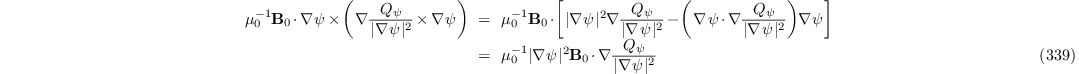

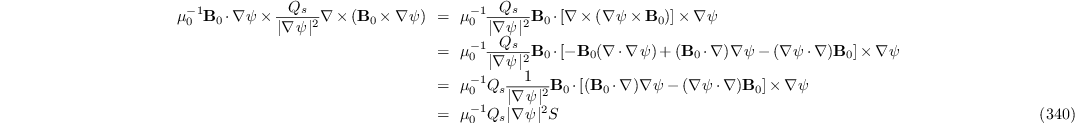

Using Eq. (337), i.e.,

|

(113) |

the second last term on the right-hand side of Eq. (111) is written

The term  in the above equation is written as

in the above equation is written as

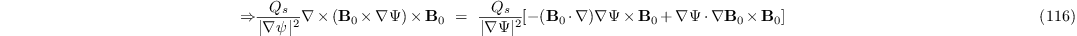

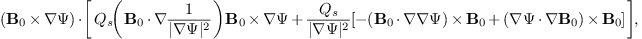

Gathering terms involving  , excluding the first

term, in expression (115) gives

, excluding the first

term, in expression (115) gives

which can be proved to be zero (refer to Sec. 9.6 for the

proof). Gathering terms involving  in expression

(115) gives

in expression

(115) gives

It can be proved that the second term of the above expression is equal

to  (refer to Sec. 9.9 for details).

Thus, from Eq. (114), we obtain

(refer to Sec. 9.9 for details).

Thus, from Eq. (114), we obtain

|

(117) |

Using Eqs. (112) and (117) in Eq. (111) yields

|

(118) |

Using  , the above equation can be arranged as

, the above equation can be arranged as

|

(119) |

which agrees with Eq. (18) in Cheng's paper[3].

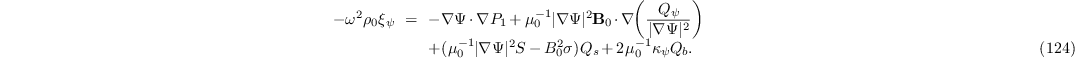

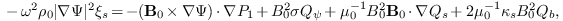

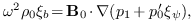

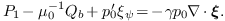

For the ease of reference, Eqs. (29), (82), (87), (99), (105), (76), and (119) are repeated here:

|

(120) |

|

(121) |

|

(122) |

|

(123) |

|

(125) |

|

(126) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

which is usually called the geodesic curvature,

,

which is usually called the geodesic curvature,  ,

which is usually called the normal curvature.

,

which is usually called the normal curvature.

as variables

as variables

Using Eqs. (121) and (122) to eliminate  ,

,  , Eqs. (124) and

(125) are written, respectively, as

, Eqs. (124) and

(125) are written, respectively, as

and

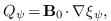

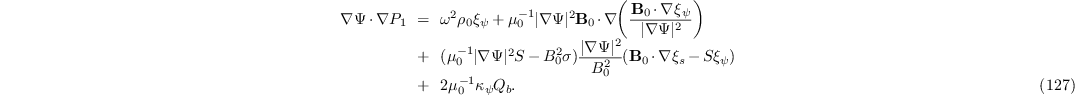

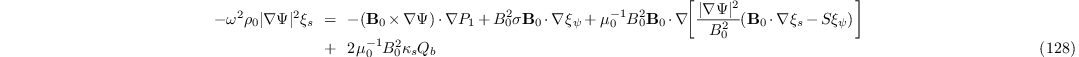

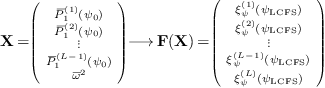

Following Ref. [3], we will express the final eigenmodes

equations in terms of the following four variables:  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and  .

In order to achieve this, we need to eliminate unwanted variables. Since

we will use

.

In order to achieve this, we need to eliminate unwanted variables. Since

we will use  instead of

instead of  as one of the variables. we write the equation (120) for

the perturbed pressure in terms of

as one of the variables. we write the equation (120) for

the perturbed pressure in terms of  variable,

which gives

variable,

which gives

|

(129) |

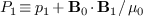

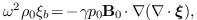

Using (129) to eliminate  in Eq. (128), we obtain

in Eq. (128), we obtain

Using pressure equation (120) to eliminate  in Eq. (126), we obtain

in Eq. (126), we obtain

|

(131) |

which can be used in Eq. (123) to eliminate  , yielding

, yielding

|

(132) |

Using Eq. (132) to eliminate  in Eq.

(129), we obtain

in Eq.

(129), we obtain

|

(133) |

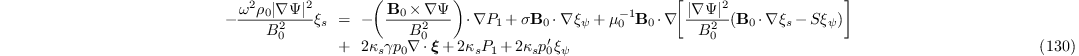

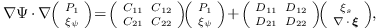

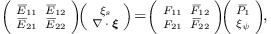

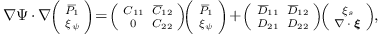

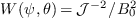

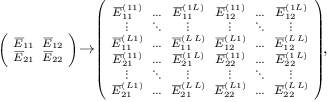

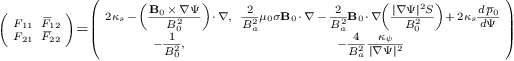

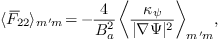

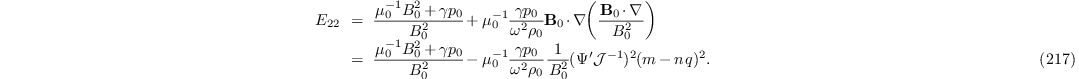

Equations (130) and (133), which involves only surface derivative operators, can be put in the following matrix form:

|

(134) |

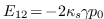

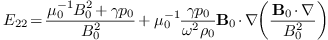

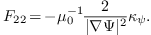

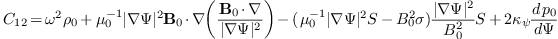

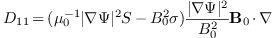

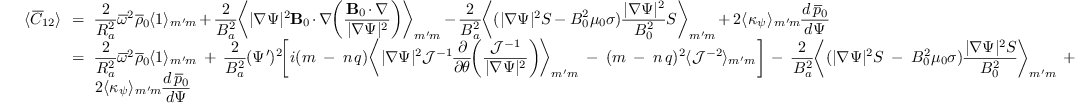

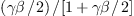

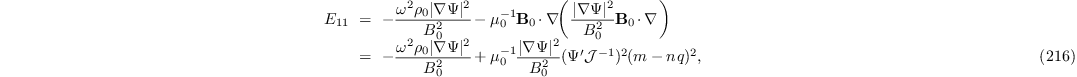

with the matrix elements given by

|

(135) |

|

(136) |

|

(137) |

|

(138) |

|

(139) |

|

(140) |

|

(141) |

|

(142) |

Equations (134)-(142) agree with equations (25), (28), and (29) of Ref [3].

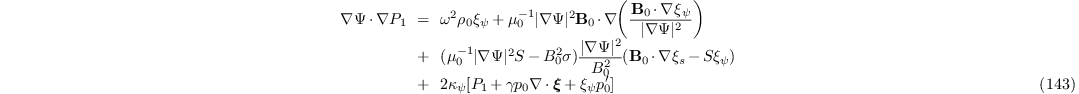

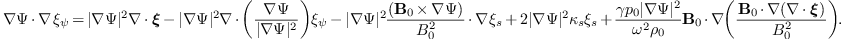

Using Eq. (129) to eliminate  in Eq.

(127), we obtain

in Eq.

(127), we obtain

The equation for the divergence of  [Eq. (95)] is written

[Eq. (95)] is written

|

(144) |

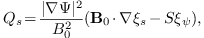

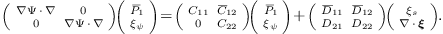

Equations (143) and (144) can be put in the following matrix form

|

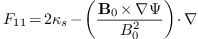

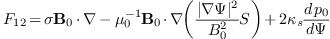

(145) |

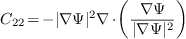

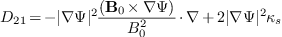

with the matrix elements given by

|

(146) |

|

(147) |

|

(148) |

|

(149) |

|

(150) |

|

(151) |

|

(152) |

|

(153) |

Equations (146)-(153) agree with Equations (26) and (27) in Ref.[3]. (It took me several months to manage to put the equations in the matrix form given here.)

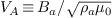

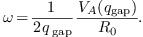

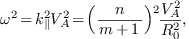

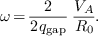

Denote the strength of the equilibrium magnetic field at the magnetic

axis by  , the mass density at the magnetic axis

by

, the mass density at the magnetic axis

by  , and the major radius of the magnetic axis by

, and the major radius of the magnetic axis by

. Define a characteristic speed

. Define a characteristic speed  ,

which is the Alfvén speed at the magnetic axis. Using the

Alfvén speed, we define a characteristic frequency

,

which is the Alfvén speed at the magnetic axis. Using the

Alfvén speed, we define a characteristic frequency  . Multiplying the matrix equation (134) by

. Multiplying the matrix equation (134) by

gives

gives

|

(154) |

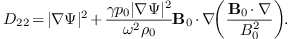

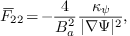

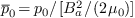

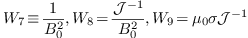

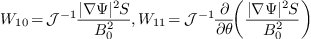

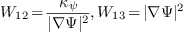

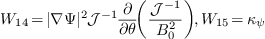

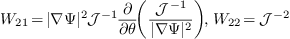

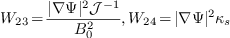

with new quantities defined as follows:  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

,

,  , and

, and  .

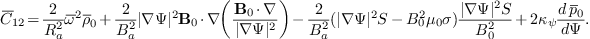

Using the equations (135), (136), (140),

(137), (138), and (142), the

expression of

.

Using the equations (135), (136), (140),

(137), (138), and (142), the

expression of  ,

, ,

,  ,

,  ,

, , and

, and  are written respectively as

are written respectively as

|

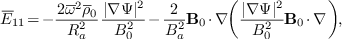

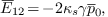

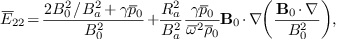

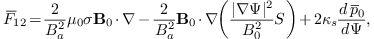

(155) |

|

(156) |

|

(157) |

|

(158) |

|

(159) |

|

(160) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  .

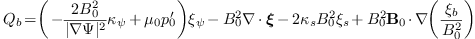

Next, consider re-normalizing the matrix equation (145).

Multiply the first equation of matrix equation (145) by

.

Next, consider re-normalizing the matrix equation (145).

Multiply the first equation of matrix equation (145) by

, giving

, giving

|

(161) |

with the new matrix elements defined as follows:  ,

,

, and

, and  . (Note that,

although the second equation of matrix equation (161) uses

. (Note that,

although the second equation of matrix equation (161) uses

, instead of

, instead of  , as a

variable , it is actually identical with the second equation of matrix

equation (145) because the

, as a

variable , it is actually identical with the second equation of matrix

equation (145) because the  term is

multiplied by zero.) Using Eqs. (147), (148)

(149) , we obtain

term is

multiplied by zero.) Using Eqs. (147), (148)

(149) , we obtain

|

(162) |

|

(163) |

|

(164) |

Note that, after the normalization, all the coefficients of the

resulting equations are of the order  , thus, are

suitable for accurate numerical calculation. Also note that, for typical

tokamak plasmas, the normalization factor

, thus, are

suitable for accurate numerical calculation. Also note that, for typical

tokamak plasmas, the normalization factor  is of

the order

is of

the order  , which is six order away from

, which is six order away from  . Therefore the normalization performed here is

necessary for accurate numerical calculation. [If the normalizing factor

is two (or less) order from

. Therefore the normalization performed here is

necessary for accurate numerical calculation. [If the normalizing factor

is two (or less) order from  , then, from my

experience, it is usually not necessary to perform additional

normalization for the purpose of optimizing the numerical accuracy,

i.e., the original units system has provided a reasonable normalization.

Of course, suitable re-normalization will be of benefit to developing a

clear physical insight into the problem in question.]

, then, from my

experience, it is usually not necessary to perform additional

normalization for the purpose of optimizing the numerical accuracy,

i.e., the original units system has provided a reasonable normalization.

Of course, suitable re-normalization will be of benefit to developing a

clear physical insight into the problem in question.]

In the above, we do not specify which coordinate system to use. In this

article, we will use the straight-line magnetic surface coordinate

system (i.e. flux coordinate system)  . The

details of this coordinate system are given in my notes on tokamak

equilibrium

(/home/yj/theory/tokamak_equilibrium/tokamak_equilibrium.tm).

. The

details of this coordinate system are given in my notes on tokamak

equilibrium

(/home/yj/theory/tokamak_equilibrium/tokamak_equilibrium.tm).

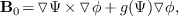

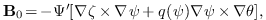

Any axisymetrical magnetic field consistent with the equilibrium

equation  can be written in the form

can be written in the form

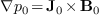

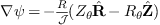

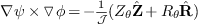

where  . In the straight-line magnetic surface

coordinates system

. In the straight-line magnetic surface

coordinates system  , the contra-variant form of

the equilibrium magnetic field is expressed as

, the contra-variant form of

the equilibrium magnetic field is expressed as

|

(165) |

where  . The covariant form of the equilibrium

magnetic field is given by

. The covariant form of the equilibrium

magnetic field is given by

|

(166) |

where  is the Jacobian of

is the Jacobian of  coordinate system.

coordinate system.

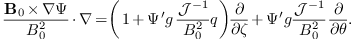

The form of the radial differential operator  in

in

coordinates is given by

coordinates is given by

|

(167) |

(Refer to my notes “tokamak_equilibrium.tm” for the proof.)

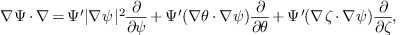

The MHD eigenmode equations (154) and (161)

involve two surface operators,  and

and  (they are called surface operators because they involve

only differential on magnetic surfaces). Next, we provide the form of

the two operators in flux coordinate system

(they are called surface operators because they involve

only differential on magnetic surfaces). Next, we provide the form of

the two operators in flux coordinate system  .

Using Eq. (165), the

.

Using Eq. (165), the  operator

(usually called magnetic differential operator) is written

operator

(usually called magnetic differential operator) is written

|

(168) |

Using the covariant form of the equilibrium magnetic field [Eq. (166)], the  operator is written

operator is written

|

(169) |

and

and

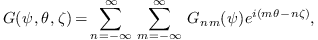

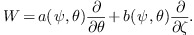

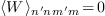

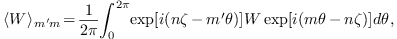

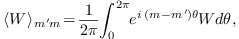

A perturbation  must be a periodic function of

the poloidal angle

must be a periodic function of

the poloidal angle  and toroidal angle

and toroidal angle  , and thus can be expanded as the following two-dimensional

Fourier series,

, and thus can be expanded as the following two-dimensional

Fourier series,

|

(170) |

where the expansion coefficient  is given by

is given by

|

(171) |

Our next task is to derive the equations for the coefficients  .

.

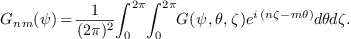

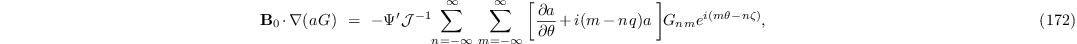

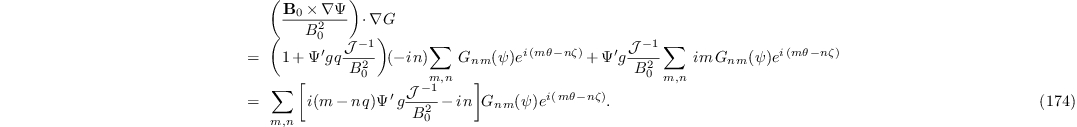

Next, consider the calculation of the surface operators acting on the above perturbation. Using Eqs. (168) and (170), we obtain

where  is a known function that is independent of

is a known function that is independent of

. Similarly, we have

. Similarly, we have

Using Eq. (169), we obtain

,

,  ,

,  , and

, and

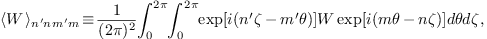

The elements of matrix  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  are two dimensional

differential operators about

are two dimensional

differential operators about  , which can be

called surface differential operators. As discussed above, we use

Fourier expansion to treat the differential with respect to

, which can be

called surface differential operators. As discussed above, we use

Fourier expansion to treat the differential with respect to  and

and  . In this method, we need to

take inner product between different Fourier harmonics (this is the

standard spectrum method, instead of the pseudo-spectral method). Noting

this, we recognize that it is useful to define the following inner

product operator:

. In this method, we need to

take inner product between different Fourier harmonics (this is the

standard spectrum method, instead of the pseudo-spectral method). Noting

this, we recognize that it is useful to define the following inner

product operator:

where  is a surface differential operator of the

following form

is a surface differential operator of the

following form

|

(175) |

Because both of the coefficients in expression (175) are

independent of  , it is ready to see that, for

, it is ready to see that, for

,

,  . This indicates that

. This indicates that

with different

with different  are

decoupled with each other.

are

decoupled with each other.

For notation ease,  is denoted by

is denoted by  when

when  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

[For the special case that  is an algebra

operator

is an algebra

operator  , equation (175) can be

reduced to

, equation (175) can be

reduced to

|

(176) |

where  is independent of

is independent of  because, as we will see below,

because, as we will see below,  is determined by

equilibrium quantities (for example,

is determined by

equilibrium quantities (for example,  ), which is

axisymetrical. Expression (176) is a Fourier integration

over the interval

), which is

axisymetrical. Expression (176) is a Fourier integration

over the interval  , which can be efficiently

calculated by using the FFT algorithm (details are given in Chapter 13.9

of Ref. [5]).] After using the Fourier harmonics expansion

and taking the inner product, every element of the matrices

, which can be efficiently

calculated by using the FFT algorithm (details are given in Chapter 13.9

of Ref. [5]).] After using the Fourier harmonics expansion

and taking the inner product, every element of the matrices  , and

, and  becomes a

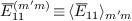

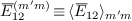

becomes a  matrix, where

matrix, where  is the total number of the Fourier

harmonics included in the expansion. Taking the matrix

is the total number of the Fourier

harmonics included in the expansion. Taking the matrix  as an example, it is discretized as

as an example, it is discretized as

|

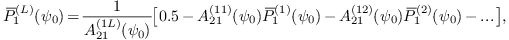

(177) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

. Next, let us derive the expressions of

. Next, let us derive the expressions of  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

. The goal of the derivation is to perform the

surface differential operators so that all the inner products take the

form of the Fourier integration given by Eq. (176). For the

convenience of reference, the expression of matrix

. The goal of the derivation is to perform the

surface differential operators so that all the inner products take the

form of the Fourier integration given by Eq. (176). For the

convenience of reference, the expression of matrix  is repeated here:

is repeated here:

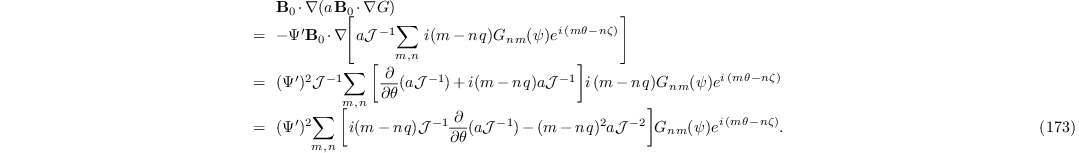

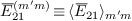

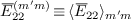

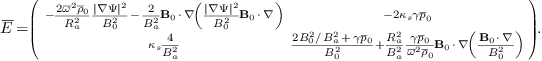

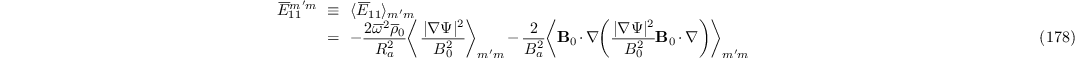

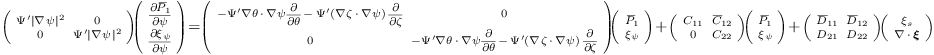

Then  is written as

is written as

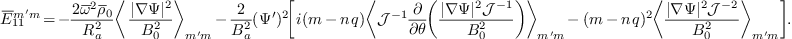

Making use of Eq. (173), equation (178) is written as

|

(179) |

Note that all the operators within the inner operator  of the above equation are algebra operators. Therefore the calculation

of the inner product

of the above equation are algebra operators. Therefore the calculation

of the inner product  reduces to the calculation

of the Fourier integration (176), which can be efficiently

calculated by using the FFT algorithm (it is thus implemented in GTAW

code). Similarly, the discrete form of the other matrix elements are

written respectively as:

reduces to the calculation

of the Fourier integration (176), which can be efficiently

calculated by using the FFT algorithm (it is thus implemented in GTAW

code). Similarly, the discrete form of the other matrix elements are

written respectively as:

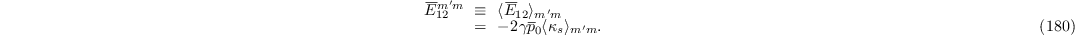

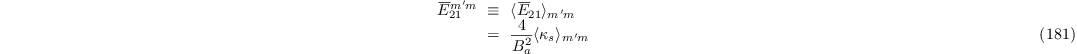

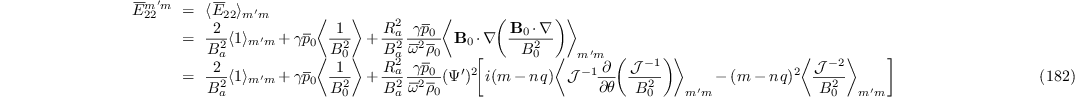

Next, consider the discrete form of the normalized  matrix, which is given by

matrix, which is given by

|

(183) |

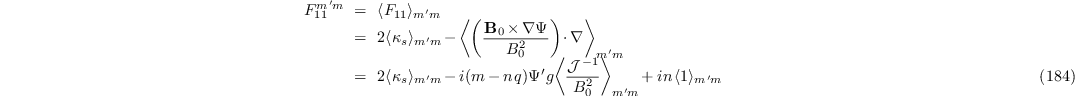

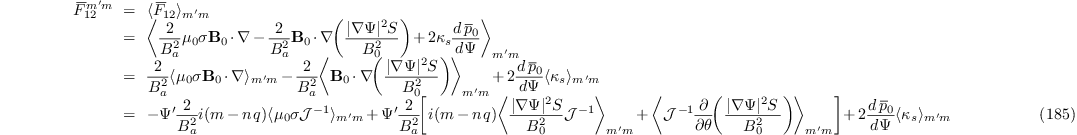

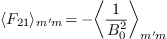

Using Eqs. (139) and (159), we obtain

|

(186) |

|

(187) |

Next, we derive the discrete form of matrix  and

and

. Before doing this, we examine matrix equation

(161), which can be written as

. Before doing this, we examine matrix equation

(161), which can be written as

|

(188) |

Using the expression of the operator  , i.e.,

, i.e.,

|

(189) |

equation (188) is written as

|

(190) |

Define the first matrix on the r.h.s of the above equation as  , then

, then  , and

, and  and

and  are given by

are given by

|

(191) |

Then

|

(192) |

|

(193) |

|

(194) |

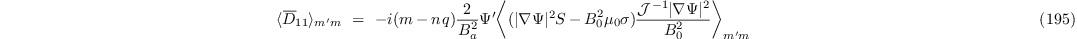

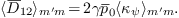

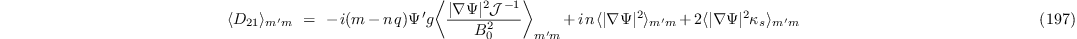

The formula for calculating the right-hand side of Eq. (194) is given in Sec. 8.6.

|

(196) |

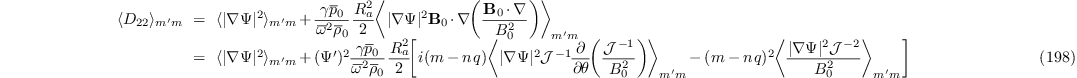

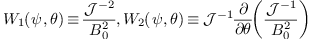

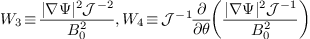

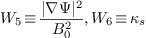

In the GTAW code, the weight functions appearing in the Fourier integration are numbered as follows:

|

(199) |

|

(200) |

|

(201) |

|

(202) |

|

(203) |

|

(204) |

|

(205) |

|

(206) |

|

(207) |

|

(208) |

|

(209) |

|

(210) |

|

(211) |

The formulas for calculating the equilibrium quantities, such as the

geodesic curvature  , normal curvature

, normal curvature  , and the local magnetic shear

, and the local magnetic shear  , are

given in Sec. 8.4.

, are

given in Sec. 8.4.

In the GTAW code, the matrix elements  and

and  are multiplied by

are multiplied by  (check

whether this will make

(check

whether this will make  a root of

a root of  ?). After this, the matrix elements

?). After this, the matrix elements  can be written in the following form

can be written in the following form

|

(212) |

where  and

and  are

are  matrix which are both independent of

matrix which are both independent of  .

.

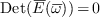

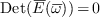

The continua are determined by the condition that  ,

which is the condition that the matrix equation

,

which is the condition that the matrix equation  has nonzero solutions. Using Eq. (212), the matrix equation

has nonzero solutions. Using Eq. (212), the matrix equation

can be written

can be written

|

(213) |

Thus finding  that can make

that can make  have nonzero solution reduces to finding the eigenvalues of the

generalized eigenvalue problem in Eq. (213). In GTAW code,

the generalized eigenvalue problem in Eq. (213) is solved

numerically by using the zggev subroutine in Lapack

library. The numerical results of the continuous spectrum are given in

Sec. 8.2.

have nonzero solution reduces to finding the eigenvalues of the

generalized eigenvalue problem in Eq. (213). In GTAW code,

the generalized eigenvalue problem in Eq. (213) is solved

numerically by using the zggev subroutine in Lapack

library. The numerical results of the continuous spectrum are given in

Sec. 8.2.

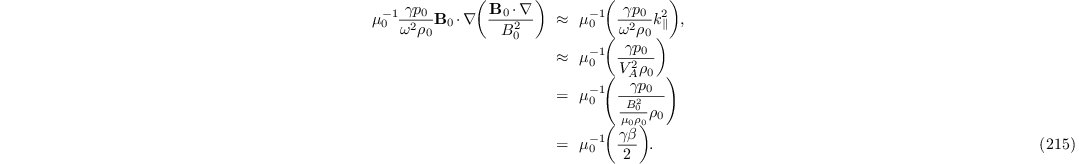

Before we give the numerical solution for the continuous spectrum, we consider some approximations that can be made when solving continuous spectrum.

Examining the expression (138) for matrix element  , we find that the first term of

, we find that the first term of  can be written as

can be written as

|

(214) |

where  , while the second term of

, while the second term of  can be written as

can be written as

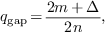

where  is the parallel wave vector and we have

used the approximation

is the parallel wave vector and we have

used the approximation  . Using Eqs. (214)

and (215), the ratio of the second term to the first term

of

. Using Eqs. (214)

and (215), the ratio of the second term to the first term

of  is written as

is written as  . For

low

. For

low  (

( ) equilibrium, the

ratio is small and therefore the second term of

) equilibrium, the

ratio is small and therefore the second term of  can be dropped. This approximation is called the slow sound

approximation in the literature[6, 7].

Numerical results indicate this approximation will remove all the sound

continua while keeping the Alfven continua nearly unchanged.

can be dropped. This approximation is called the slow sound

approximation in the literature[6, 7].

Numerical results indicate this approximation will remove all the sound

continua while keeping the Alfven continua nearly unchanged.

If we set all the thermal pressure terms in  and

and

to be zero (this is equivalent with setting

to be zero (this is equivalent with setting  ), the sound wave will be removed from the system.

This approximation is called zero beta limit in literature[6].

Numerical results indicate the zero beta limit will remove all the sound

continua. Compared with the slow sound approximation, the zero beta

limit will make the frequency of the Alfven continua a little lower, and

make the zeroth continua gaps (BAE gaps) disappear[7].

), the sound wave will be removed from the system.

This approximation is called zero beta limit in literature[6].

Numerical results indicate the zero beta limit will remove all the sound

continua. Compared with the slow sound approximation, the zero beta

limit will make the frequency of the Alfven continua a little lower, and

make the zeroth continua gaps (BAE gaps) disappear[7].

Consider the form of matrix  in the cylindrical

geometry limit, in which the equilibrium quantities are independent of

poloidal angle. Equation (284) indicates that the geodesic

curvature

in the cylindrical

geometry limit, in which the equilibrium quantities are independent of

poloidal angle. Equation (284) indicates that the geodesic

curvature  is zero in this case. Thus, the matrix

elements

is zero in this case. Thus, the matrix

elements  and

and  are zero.

Next, consider the matrix elements

are zero.

Next, consider the matrix elements  and

and  . Because all equilibrium quantities are independent of the

poloidal angle, different poloidal harmonics of the perturbation are

decoupled. Therefore, we can consider a perturbation with a single

poloidal mode number . For a poloidal harmonic with poloidal mode number

. Because all equilibrium quantities are independent of the

poloidal angle, different poloidal harmonics of the perturbation are

decoupled. Therefore, we can consider a perturbation with a single

poloidal mode number . For a poloidal harmonic with poloidal mode number

, matrix element

, matrix element  is

written

is

written

and matrix element  is written

is written

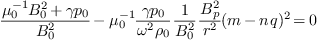

The continua are the roots of the equation  ,

which, in the cylindrical geometry limit, reduces to

,

which, in the cylindrical geometry limit, reduces to

|

(218) |

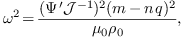

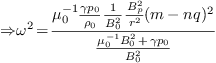

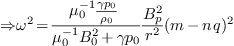

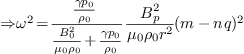

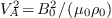

Two branches of the roots of Eq. (218) are given by  and

and  , respectively. The

equation

, respectively. The

equation  is written

is written

|

(219) |

which gives

|

(220) |

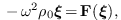

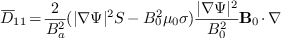

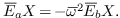

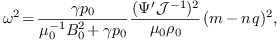

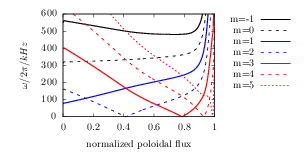

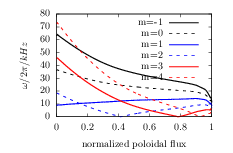

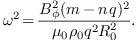

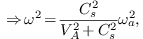

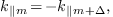

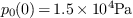

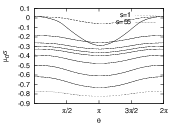

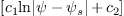

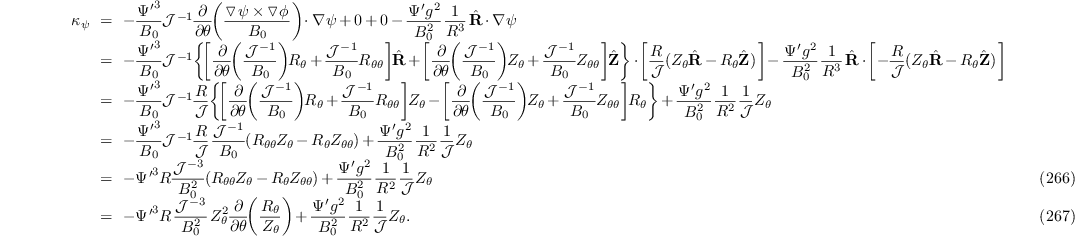

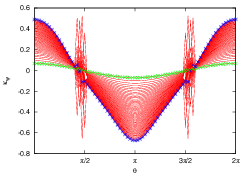

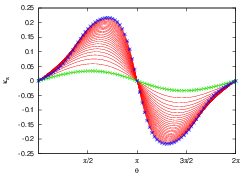

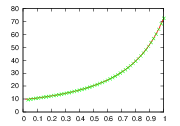

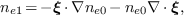

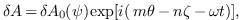

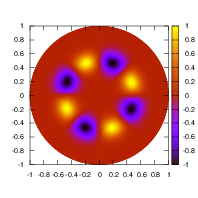

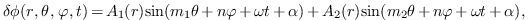

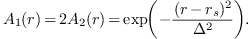

which is the Alfvén branch of the continua. Figure 1a

plots the results of Eq. (220). The equation  is written

is written

|

(221) |

which is the sound branch of the continua. Figure 1b plots the results of Eq. (221).

|

Figure 1. |

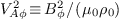

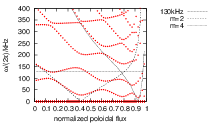

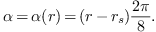

Figures 2 compares the Alfven continua in the cylindrical limit with those in the toroidal geometry. The results indicate that the Alfven continua in the toroidal geometry reconnect, forming gaps near the locations where the Alfven continua in the cylindrical limit intersect each other.

The result in Eq. (220) is not clear from the physical point of view since it involves the Jacobian, which is a mathematical factor due to the freedom in the choice of coordinates. Next, we try to write the right-hand side of Eq. (220) in more physical form. In cylindrical geometry limit, magnetic surfaces are circular. Thus the radial coordinate can be chosen to be the geometrical radius of the circular magnetic surface, and the usual poloidal angle (i.e., equal-arc angle) can be used as the poloidal coordinate. Then the poloidal magnetic flux is written as

|

(222) |

where  is the length of the cylinder. We know

that

is the length of the cylinder. We know

that  used in the Grad-Shafranov equation is

related to

used in the Grad-Shafranov equation is

related to  by

by

|

(223) |

Using Eqs. (222) and (223), we obtain

|

(224) |

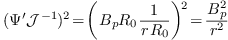

Next, we calculate the Jacobian  , which is

defined by

, which is

defined by

|

(225) |

Since we choose  and

and  (the

positive direction of

(the

positive direction of  is count clockwise when

observers view along the positive direction of

is count clockwise when

observers view along the positive direction of  ),

the above equation is written

),

the above equation is written

Using Eqs. (224) and (226) ,  is written

is written

|

(227) |

Using these, Eq. (220) is written

|

(228) |

Using the definition of safety factor in the cylindrical geometry

|

(229) |

equation (228) is written

|

(230) |

In the cylindrical geometry, the parallel (to equilibrium magnetic field) wave-number is given by

|

(231) |

Using this, Eq. (230) is written

|

(232) |

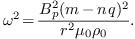

Using the definition of Alfven speed  , the above

equation is written as

, the above

equation is written as

|

(233) |

which gives the well known Alfven resonance condition. For later use, define

|

(234) |

then Eq. (228) is written as  .

.

Similarly, by using Eq. (227), equation (217)

for  is written as

is written as

Then equation  reduces to

reduces to

|

(235) |

|

(236) |

where  ,

,  . Equation (166) gives the sound branch of the continua. For present

tokamak plasma parameters,

. Equation (166) gives the sound branch of the continua. For present

tokamak plasma parameters,  is usually one order

smaller than

is usually one order

smaller than  . Thus, equation (236)

indicates the sound continua are much smaller than the Alfven continua

for the same

. Thus, equation (236)

indicates the sound continua are much smaller than the Alfven continua

for the same  and

and  .

.

In the cylindrical geometry, continua with different poloidal mode

numbers will intersect each other, as shown in Fig. 1.

Next, we calculate the radial location of the intersecting point of two

continua with poloidal mode number  and

and  , respectively. In the intersecting point, we have

, respectively. In the intersecting point, we have

|

(237) |

i.e.

|

(238) |

which gives

|

(239) |

or

|

(240) |

Inspecting the expression for  in Eq. (323),

i.e.,

in Eq. (323),

i.e.,

we know that only the case in Eq. (240) is possible, which gives

|

(241) |

which further reduces to

|

(242) |

The above equation determines the radial location where the  continuum intersect the

continuum intersect the  continuum.

Note that a mode with two poloidal modes has two corresponding resonant

surfaces. For the case where the mode has

continuum.

Note that a mode with two poloidal modes has two corresponding resonant

surfaces. For the case where the mode has  and

and

poloidal harmonics, the resonant surfaces are

respectively

poloidal harmonics, the resonant surfaces are

respectively  and

and  . Note

that the value of

. Note

that the value of  given in Eq. (242)

is between the above two values.

given in Eq. (242)

is between the above two values.

In toroidal geometry, the different poloidal modes are coupled, and the continuum will “reconnect” to form a gap in the vicinity of the original intersecting point, as shown in Fig. 2. Therefore the original intersecting point, Eq. (242), gives the approximate location of the gap. Furthermore, using Eq. (242), we can determine the frequency of the intersecting point, which is given by

|

(243) |

which can be further written

|

(244) |

According to the same reasoning given in the above, Eq. (244) is an approximation to the center frequency of the TAE gap. The frequency and the location given above are also an approximation to the frequency and location of the TAE modes that lie in the gap.

For the ellipticity-induced gap (EAE gap), which is formed due to the

coupling of  and

and  harmonics, the location is approximately determined by

harmonics, the location is approximately determined by

|

(245) |

which gives

|

(246) |

and the approximate center angular frequency is

|

(247) |

which can be written as

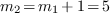

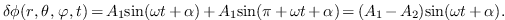

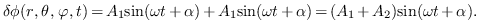

Generally, for the gap formed due to the coupling of  and

and  harmonics, we have

harmonics, we have

which gives

|

(248) |

and

|

(249) |

Equation (249) can also be written as

|

(250) |

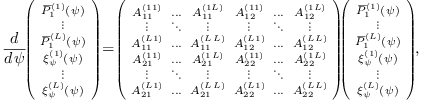

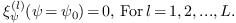

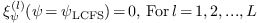

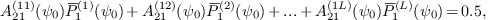

After using Fourier spectrum expansion and taking the inner product over

, Eq. (190) can be written as the

following system of ordinary differential equations:

, Eq. (190) can be written as the

following system of ordinary differential equations:

|

(251) |

where  is the total number of the poloidal

harmonics included in the Fourier expansion, the matrix elements

is the total number of the poloidal

harmonics included in the Fourier expansion, the matrix elements  are functions of

are functions of  and

and  . Next, we specify the boundary condition for the

system. Note that equations system (251) has

. Next, we specify the boundary condition for the

system. Note that equations system (251) has  first-order differential equations, for which we need to

specify

first-order differential equations, for which we need to

specify  boundary conditions to make the solution

unique. The geometry determines that the radial displacement at the

magnetic axis must be zero, i.e.,

boundary conditions to make the solution

unique. The geometry determines that the radial displacement at the

magnetic axis must be zero, i.e.,

|

(252) |

We consider only the modes that vanish at the plasma boundary, for which we have the following boundary conditions:

|

(253) |

Now Eqs. (252) and (253) provide  boundary conditions, half of which are at the boundary

boundary conditions, half of which are at the boundary

and half are at the boundary

and half are at the boundary  .

Therefore equations system (251) along with the boundary

conditions Eqs. (252) and (253) constitutes a

standard two-points boundary problem[5]. Note, however,

that we are solving a eigenvalue problem, for which there is an

additional equation for

.

Therefore equations system (251) along with the boundary

conditions Eqs. (252) and (253) constitutes a

standard two-points boundary problem[5]. Note, however,

that we are solving a eigenvalue problem, for which there is an

additional equation for  :

:

|

(254) |

This increases the number of equations by one and so we need one

additional boundary condition. Note that, by eliminating all  , equations system (251) can be written as a

system of second-order differential equations for

, equations system (251) can be written as a

system of second-order differential equations for  .

Further note that the unknown functions

.

Further note that the unknown functions  satisfy

homogeneous equations and homogeneous boundary conditions, which

indicates that if

satisfy

homogeneous equations and homogeneous boundary conditions, which

indicates that if  with

with  are solutions, then

are solutions, then  are also solutions to the

original equations, where

are also solutions to the

original equations, where  is a constant.

Therefore the value of the derivative of

is a constant.

Therefore the value of the derivative of  at the

boundary have one degree of freedom. Due to this fact, one of the

derivatives

at the

boundary have one degree of freedom. Due to this fact, one of the

derivatives  ,

,  ,…,

,…,

at

at  can be set to be a

nonzero value. For example, setting the value of

can be set to be a

nonzero value. For example, setting the value of  at

at  to be

to be  and making use

of

and making use

of  at

at  , we obtain

, we obtain

|

(255) |

which can be solved to give

|

(256) |

which provides the additional boundary condition we need. In the present

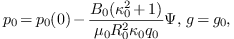

version of my code, for convenience, I directly set the value of  to a small value, instead of using Eq. (256).

The following sketch map describes the function

to a small value, instead of using Eq. (256).

The following sketch map describes the function  for which we need to find roots in the shooting process.

for which we need to find roots in the shooting process.

|

(257) |

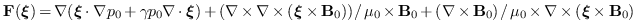

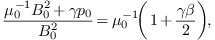

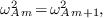

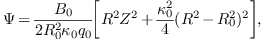

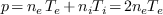

To benchmark GTAW code, we use it to calculate the continua and gap modes of the Solovev equilibrium and compare the results with those given by NOVA code. The Solovev equilibrium used in the benchmark case is given by

|

(258) |

|

(259) |

with  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and  . The flux surface

with the minor radius being

. The flux surface

with the minor radius being  (corresponding to

(corresponding to

) is chosen as the boundary flux surface. Main

plasma is taken to be Deuterium and the number density is taken to be

uniform with

) is chosen as the boundary flux surface. Main

plasma is taken to be Deuterium and the number density is taken to be

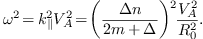

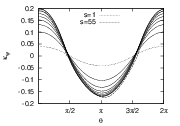

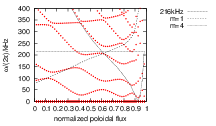

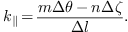

uniform with  . Figure 3 compares the

Alfven continua calculated by NOVA and GTAW, which shows good agreement

between them.

. Figure 3 compares the

Alfven continua calculated by NOVA and GTAW, which shows good agreement

between them.

|

Figure 3. Comparison of the |

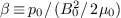

A gap mode with frequency  is found in the NAE

gap by both NOVA and GTAW. The poloidal mode numbers of the two dominant

harmonics are

is found in the NAE

gap by both NOVA and GTAW. The poloidal mode numbers of the two dominant

harmonics are  and

and  , which

is consistent with the fact that a NAE is formed due to the coupling

between

, which

is consistent with the fact that a NAE is formed due to the coupling

between  and

and  harmonics.

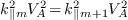

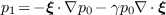

Before comparing the radial structure of the poloidal harmonics given by

the two codes, a discussion about the assumption adopted in NOVA is

desirable. As is pointed out by Dr. Gorelenkov, NOVA at present is

restricted to up-down symmetric equilibrium and, for this case, it can

be shown that the amplitude of all the radial displacement can be

transformed to real numbers. For this reason, NOVA use directly real

numbers for the radial displacement in its calculation. In GTAW code,

the amplitude of the poloidal harmonics of the radial displacement are

complex numbers. The Solovev equilibrium used here is up-down symmetric

and the results given by GTAW indicate the poloidal harmonics of the

radial displacement can be transformed (by multiplying a constant such

as

harmonics.

Before comparing the radial structure of the poloidal harmonics given by

the two codes, a discussion about the assumption adopted in NOVA is

desirable. As is pointed out by Dr. Gorelenkov, NOVA at present is

restricted to up-down symmetric equilibrium and, for this case, it can

be shown that the amplitude of all the radial displacement can be

transformed to real numbers. For this reason, NOVA use directly real

numbers for the radial displacement in its calculation. In GTAW code,

the amplitude of the poloidal harmonics of the radial displacement are

complex numbers. The Solovev equilibrium used here is up-down symmetric

and the results given by GTAW indicate the poloidal harmonics of the

radial displacement can be transformed (by multiplying a constant such

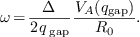

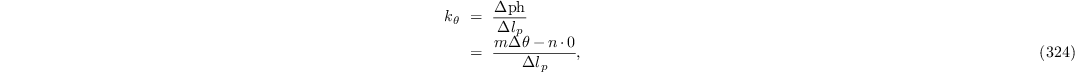

as  ) to real numbers. After transforming the

radial displacement to real numbers, the results can be compared with

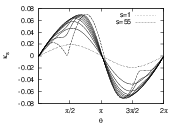

those of NOVA. Figure 4 compares the radial structure of

the dominant poloidal harmonics

) to real numbers. After transforming the

radial displacement to real numbers, the results can be compared with

those of NOVA. Figure 4 compares the radial structure of

the dominant poloidal harmonics  given by the two

codes, which indicates the results given by the two codes agree with

each other well.

given by the two

codes, which indicates the results given by the two codes agree with

each other well.

|

Figure 4. The dominant poloidal

harmonics ( |

|

Figure 5. Slow sound approximation of the |

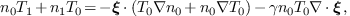

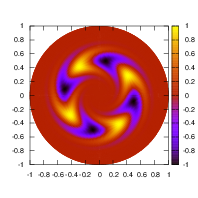

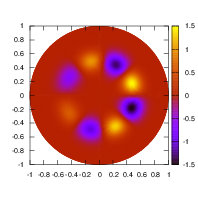

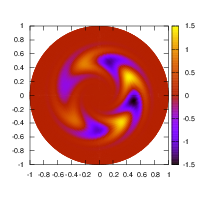

Figure 6 plots the mode structure of the NAE on  plane, which shows that the mode has an anti-ballooning

structure, i.e., the mode is stronger at the high-field side than at the

low-field side.

plane, which shows that the mode has an anti-ballooning

structure, i.e., the mode is stronger at the high-field side than at the

low-field side.

|

Figure 6. Two dimension mode

structure of the NAE in Fig. 4. The dashed line in

the figure indicates the boundary magnetic surface and the small

circle indicates the inner boundary used in the numerical

calculation.

|

|

Figure 7. Real part (a), imaginary part (b), and

absolute value of the amplitude (c) of the poloidal harmonics of a

|

|

Figure 8. Slow sound approximation of the

continua of the Solovev equilibrium. Also plotted are the

frequency of the TAE ( |

For the case that  , a TAE with

, a TAE with  is found in the TAE gap. The radial dependence of the poloidal harmonics

of the mode is plotted in Fig. 9. Figure 10

plots the frequency of the mode on the Alfven continua graphic.

is found in the TAE gap. The radial dependence of the poloidal harmonics

of the mode is plotted in Fig. 9. Figure 10

plots the frequency of the mode on the Alfven continua graphic.

|

Figure 9. Real part (a), imaginary

part (b), and absolute value of the amplitude (c) of the poloidal

harmonics of a |

|

Figure 10. Slow sound approximation

of the continua of the Solovev equilibrium. Also plotted are the

frequency of the TAE ( |

The content in this section has been published in my 2014 paper[8].

The tokamak equilibrium used in this paper is reconstructed by EFIT code

by using the information of profiles measured in EAST experiment[9]. The shape of flux surfaces within the last-closed-flux

surface (LCFS) are plotted in Fig. 11, where  curves are also plotted. In the paper, I said that the

equilibrium was a double-null configuration with the LCFS connected to

the lower X point. This is wrong. The configuration with the LCFS

connected to the lower X point should be called lower single null

configuration. The double-null configuration is a configuration with

LCFS connected to both the lower and upper X points. In practice, if the

spacial seperation between the flux surface connected to the low X point

and the flux surface connected to the upper X point,

curves are also plotted. In the paper, I said that the

equilibrium was a double-null configuration with the LCFS connected to

the lower X point. This is wrong. The configuration with the LCFS

connected to the lower X point should be called lower single null

configuration. The double-null configuration is a configuration with

LCFS connected to both the lower and upper X points. In practice, if the

spacial seperation between the flux surface connected to the low X point

and the flux surface connected to the upper X point,  ,

is smaller than a value (e.g. 1cm), the configuration can be considered

as a double null configuration, where

,

is smaller than a value (e.g. 1cm), the configuration can be considered

as a double null configuration, where  is the

spacial separation between the two flux surfaces on the low-field side

of the midplane.

is the

spacial separation between the two flux surfaces on the low-field side

of the midplane.

The profiles of safety factor, pressure, and electron number density are plotted in Fig. 12.

The mass density  is calculated from

is calculated from  , where

, where  is the mass of the main

ions (deuterium ions in this discharge),

is the mass of the main

ions (deuterium ions in this discharge),  is the

number density of the ions, which is inferred from

is the

number density of the ions, which is inferred from  by using the neutral condition

by using the neutral condition  (impurity ions

are neglected).

(impurity ions

are neglected).

|

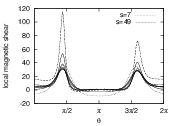

Figure 13. Normal and geodesic magnetic

curvature as a function of the poloidal angle. Different lines in

the figure correspond to different magnetic surfaces.

|

|

Figure 14. Negative local magnetic

shear |

|

Figure 15. |

The eigenfrequency of Eq. (213),  ,

as a function of the radial coordinate gives the continua for the

equilibrium. It can be proved analytically that the eigenfrequency of

Eq. (213),

,

as a function of the radial coordinate gives the continua for the

equilibrium. It can be proved analytically that the eigenfrequency of

Eq. (213),  , is a real number (I do

not prove this). Making use of this fact, we know that a crude method of

finding the eigenvalue of Eq. (213) is to find the zero

points of the real part of the determinant of

, is a real number (I do

not prove this). Making use of this fact, we know that a crude method of

finding the eigenvalue of Eq. (213) is to find the zero

points of the real part of the determinant of  .

Since, in this case, both the independent variables and the value of the

function are real, the zero points can be found by using a simple

one-dimension root finder. This method was adopted in the older version

of GTAW (bisection method is used to find roots). In the latest version

of GTAW, as mentioned above, the generalized eigenvalue problem in Eq.

(213) is solved numerically by using the

zggev subroutine in Lapack library. (The eigenvalue

problem is solved without the assumption that

.

Since, in this case, both the independent variables and the value of the

function are real, the zero points can be found by using a simple

one-dimension root finder. This method was adopted in the older version

of GTAW (bisection method is used to find roots). In the latest version

of GTAW, as mentioned above, the generalized eigenvalue problem in Eq.

(213) is solved numerically by using the

zggev subroutine in Lapack library. (The eigenvalue

problem is solved without the assumption that  is

real number. The eigenvalue

is

real number. The eigenvalue  obtained from the

routine is very close to a real number, which is consistent with the

analytical conclusion that the eigenvalue

obtained from the

routine is very close to a real number, which is consistent with the

analytical conclusion that the eigenvalue  must

be a real number.)

must

be a real number.)

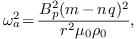

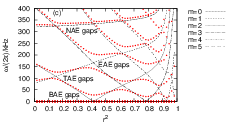

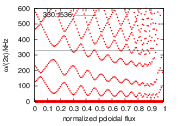

Figure 16 plots the eigenfrequency of Eq. (213)

as a function of the radial coordinate  . The

result is calculated in the slow sound approximation, thus giving only

the Alfven branch of the continua. Also plotted in Fig. 16

are the Alfven continua in the cylindrical limit. As shown in Fig. 16, the Alfven continua in toroidal geometry do not intersect

each other, thus forming gaps at the locations where the cylindrical

Alfven continua intersect each other.

. The

result is calculated in the slow sound approximation, thus giving only

the Alfven branch of the continua. Also plotted in Fig. 16

are the Alfven continua in the cylindrical limit. As shown in Fig. 16, the Alfven continua in toroidal geometry do not intersect

each other, thus forming gaps at the locations where the cylindrical

Alfven continua intersect each other.

The first gap, which is formed due to the coupling of sound wave and

Alfven wave, starts from zero frequency. This gap is called BAE gap

since beta-induced Alfven eigenmode (BAE) can exist in this gap. The

second gap is called TAE gap, which is formed mainly due to the coupling

of  and

and  poloidal

harmonics. The third gap is called EAE gap, which is formed mainly due

to the coupling of

poloidal

harmonics. The third gap is called EAE gap, which is formed mainly due

to the coupling of  and

and  poloidal harmonics. The fourth gap is called NAE gap, which is formed

due to the coupling of

poloidal harmonics. The fourth gap is called NAE gap, which is formed

due to the coupling of  and

and  poloidal harmonics. A gap can be further divided into sub-gaps according

to the two dominant poloidal harmonics that are involved in forming the

gap. For example, a sub-gap of the TAE gap is the one that is formed

mainly due to the coupling of

poloidal harmonics. A gap can be further divided into sub-gaps according

to the two dominant poloidal harmonics that are involved in forming the

gap. For example, a sub-gap of the TAE gap is the one that is formed

mainly due to the coupling of  and

and  harmonics. For the ease of discussion, we call this

sub-gap “

harmonics. For the ease of discussion, we call this

sub-gap “ sub-gap”, where the two

numbers stand for the poloidal mode numbers. The frequency range of a

sub-gap is defined by the frequency difference of the two extreme points

on the continua. The radial range of the sub-gap can be defined as the

radial region whose center is the location of one of the extreme points

on the continua, width is the half width between the neighbor left and

right extreme points.

sub-gap”, where the two

numbers stand for the poloidal mode numbers. The frequency range of a

sub-gap is defined by the frequency difference of the two extreme points

on the continua. The radial range of the sub-gap can be defined as the

radial region whose center is the location of one of the extreme points

on the continua, width is the half width between the neighbor left and

right extreme points.

|

Figure 16. |

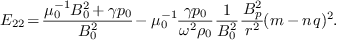

Figure 17 compares the continua of the full ideal MHD model

with those of slow sound and zero  approximations. The results indicate that the slow sound approximation

eliminates the sound continua while keeps the Alfven continua almost

unchanged. The zero

approximations. The results indicate that the slow sound approximation

eliminates the sound continua while keeps the Alfven continua almost

unchanged. The zero  approximation eliminates the

BAE gap.

approximation eliminates the

BAE gap.

(Numerical results indicate that the eigenvalue  is always grater than or equal to zero. Can this point be proved

analytically?)

is always grater than or equal to zero. Can this point be proved

analytically?)

In order to verify the numerical convergence about the number of the

poloidal harmonics included in the expansion, we compares the results

obtained when the poloidal harmonic numbers are truncated in the range

and those obtained when the truncation region is

and those obtained when the truncation region is

. The results are plotted in Fig. 18,

which shows that the two results agree with each other very well for the

low order continua in the core region of the plasma. For continua in the

edge region or higher order continua, there are some discrepancies

between the two results. These discrepancies are due to that higher

order poloidal harmonics are needed in evaluating the continua for those

cases.

. The results are plotted in Fig. 18,

which shows that the two results agree with each other very well for the